In her first collection of poetry, Untamed, Sandhya Mridul writes what it means to be a woman who finally stopped shrinking.

The actor, known for playing sassy, bold and bindaas women, bares her soul in a debut poetry collection, ‘Untamed,’ that traces heartbreak, rage, despair and healing. She opens up about breaking free — from silence, shame, and the need to please with honest, fierce, and deeply personal poems

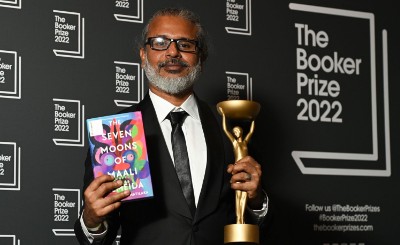

Sandhya Mridul, who has never fit into any box, may be known to most as an actor, but her debut poetry collection, Untamed (Readomania), reveals a different, even more intimate terrain. Written over years, it comes from a personal, private space. We’ve seen her in films like Saathiya, Page 3, Honeymoon Travels Pvt Ltd and Angry Indian Goddesses. We remember her from shows like Swabhimaan, Koshish, Hu Ba Hu and Tandav. She’s been a dancer, a stand-up. But in these poems — unvarnished, urgent, tender — we meet Sandhya the survivor. The thinker. The feminist. The witness. The one who bled but didn’t blink.

Across 172 searingly honest poems, Sandhya documents the anatomy of heartbreak and the long, uneven road to healing. With a voice that is both bruised and brave, she writes of desire, separation, despair, and the slow re-entry into hope. Each poem is a fragment of the emotional archaeology she has excavated. Writing became her way of unlearning numbness, of peeling off the armour built over years. The poems embody the very act of letting go, line by line. Splinters of truth lodged in the skin, they are spare, sinewy, and deeply felt, like veins pulsing with memory and rage.

Sandhya builds her verses like a survivor stacks bricks from fallen homes: raw, necessary, uneven. “How strong is strong?” she asks again and again — each time with a different wound, a different loved one, a different day to survive — in one of her poems, ‘How Strong.’ Her poems mirror her emotion: cascading lines that break mid-thought, enjambments that echo the choking rhythm of loss and grief. Even punctuation is sparse, almost withheld, as if grammar itself might interrupt the honesty of pain. Elsewhere, the architecture of her verse relies on sharp swerve — from suffering to reclamation, from confusion to clarity.

In ‘Me Too’, she slices through collective trauma with stanzas that first list devastation (“Of buried rage / And misplaced shame”) and then pivot, unflinchingly, toward rebirth: “There’s a life after / Of unfiltered dreams / And melodies unchained.” Far from being redemptive clichés, these are reclaimed breaths — short, considered, and deliberate. Even in poems like ‘Fear,’ where she writes, “I just lay there and bled / It all out,” the body becomes both battlefield and healing site. After years of speaking other people’s lines, Untamed is Sandhya Mridul speaking in her own. And she’s got something to say. Excerpts from an interview with her around her poetry:

Your poetry in Untamed cuts deep into love, grief, rage, and survival. When you say “pain is good,” are you talking about a kind of creative power in pain? Or is it also about reclaiming control over what’s wounded you?

I think it’s a bit of both, and one leads to the other. I do believe that pain can be channelled effectively into creativity, and in doing so, it becomes cathartic; it allows you to reclaim your power. You can never completely overcome or control your wounds — they don’t go away — but you can find better ways to live with them, to cope. For me, using pain creatively has been deeply healing. When I read the book back, it helped me — reading your entire journey gives you perspective, and you feel a sense of pride that you used the pain well. I truly believe creativity is one of the best uses of pain. If you can do that, it opens your heart a little more. Pain breaks you open, and if you allow yourself to break, you can create — and through that creation, you can heal. It’s all connected.

Do you think Indian women are allowed to show grief in public, or are we always expected to “be strong” in silence, like the women in your poem ‘How Strong’?

Why just women? I don’t think anyone is really allowed to grieve in public. It’s only recently, because some very popular people around the world have started talking about it, that it’s become somewhat acceptable — even seen as “cool.” But it’s not just grief; even emotions like rage are considered negative and often shunned. That kind of expression just doesn’t sit well with people. We’re only comfortable with joy — with cheerful, fun, bubbly, happy people. But no one can be that all the time. So, it’s not just women — I think men are muzzled too. The conditioning runs deep: men are told not to cry, women are told not to vocalize too much, to tolerate, to absorb. These messages build the narratives we live with. So while it may seem like we’re more open now — with all the so-called wokeness — the truth is that grief still makes people uncomfortable. It’s not easily accepted, and most people don’t know how to deal with it when it shows up.

Your poetry — especially poems like “The God Within” and “Dark Moon” — seems to come from somewhere very still, very deep. Is this spiritual for you? Or emotional? Or maybe both? Where do these poems come from?

They come from the truth. I’ve lived every moment of it. I’ve sat with those moments, accepted them, observed them from outside myself — and that’s what allowed me to write. I’ve felt those emotions deeply, allowed myself to go into dark spaces without flinching. I didn’t shy away from anything I was feeling, because honestly, I got tired of doing that. I’ve always had this image of being the cool, bold, bindaas girl. But behind that, no one saw the vulnerable girl — because I never let them. I hid my sensitivity, my vulnerability, because it was seen as weakness. I was expected to be strong. And somewhere, those definitions — fed to us from childhood, around the world — became so warped that I forgot who I truly was.

But when I sat down to write, I started reclaiming that self. With every poem in the book, I felt safe. Safe to speak through pen and paper in a way I didn’t with people — because the world judges. But my book didn’t. Every emotion here was lived, felt, and then expressed — not to perform, not to impress, but to let the poison out, to stop justifying pain or grief, to stop explaining away my truth. I made peace with the negative — with the fact that it too deserved space. And so every word I wrote is my truth. Nothing in this book is fabricated. I lived all of it.

How long have you been writing poetry?

I started stepping back a lot — even before COVID. I began taking out time for myself. Losing two of my closest friends in my early 30s was a turning point; it flipped a switch inside me. I realised I needed to create a better life-work balance. Until then, I had been so consumed by my career that I barely returned home to Delhi or met anyone. That loss made me pause and re-evaluate. I began living more consciously. I took on only the work that truly appealed to me — the kind of roles that challenged me, that meant something, that surrounded me with people I respected. It was, in a way, an act of rebellion: to say no to anything that didn’t align with my heart. I chose stillness. I chose the mountains. I chose family and friends. I eased myself out of anything that didn’t serve me, because acting is my passion and I never want to do it half-heartedly.

And I started writing. Sometimes, a thought would come, sometimes nothing for years. But it was during COVID that it became really concentrated writing — when I would actually sit down, and the words would just flow and flow. I would finish all my jobs and chores because I was alone and locked up in Bombay during COVID, and had to do all the work myself, which I actually enjoyed. But then I would take my coffee, sit at the table, and just let whatever needed to come up flow out. That’s when it truly became a thing. For two or three years, writing became part of my rhythm. But I still didn’t imagine that I’d put out a book. I didn’t yet know whether this was something just for me — or meant for the world.

I didn’t realise how much I had written — I honestly didn’t. It was only last year, when I started collating everything, that I thought, “Oh my God, this is too much work!” I couldn’t believe how much I had written. Putting it all together, organising, sorting — it just felt like a massive task. And then I went through it all. My editor said, “Listen, if you want to go through it again, if you want to edit or change something here and there, please feel free.” But how do you edit a feeling? How do you edit your journey, your experience? You can’t. There was no edit at all. I said, this isn’t about grammar — it’s about conveying something that is my truth. I’m not going to fix it just to make it sound more intelligent. I’m not going to make it contrived. It is going to be what it is.

There’s a line in your poem ‘My Poetry’ that says “you never understood my language — you called it poetry.” Do you feel like the world often misunderstands the way women express themselves — especially when it doesn’t fit into what’s palatable or poetic enough for others?

Absolutely — if you’re too vocal, you’re called arrogant or difficult. If you’re expressive or emotional or tend to cry easily, you’re labelled neurotic or psychotic. It has always been the game. There’s always a name for every feeling we express. I’ve often felt misunderstood and judged, and I’ve seen it happen to so many women. People have told me, “I was scared of you before we met — I’d heard things.” Why? Because I speak my mind. Whether it’s anger or sadness, any so-called negative emotion is unwelcome. We have no tolerance for it — only judgment.

I feel it’s time we stop diluting what we feel or shrinking ourselves just to be light. Writing this book — and more importantly, the process of writing it without even knowing it would become a book — gave me the courage to allow myself to be disliked, to be misunderstood. I said to myself: it’s okay. When I speak about mental health, people say, “Why are you talking about depressing things?” But no — this is the truth for some people, including me. We can’t just ostrich our way through life, pretending it’s not happening. I shudder to think what might come out from under some people’s rugs. The truth is, sometimes we are misunderstood, sometimes we say things that don’t sound pretty — but this isn’t the time to avoid what we don’t like to feel. That time is gone.

In your poems, one can feel the rhythm of someone who can cry and laugh in the same breath. Is humour something you’ve leaned on to survive? And is writing your way of slowly coming back to yourself?

You’ve hit the nail on the head. I’ve always been the joker of the pack. In fact, when Shabana Azmi launched my book, she said, “I was stunned to read Sandhya’s book — she’s the joker of our group!” My closest friends know I’ve always been the mad one — the Page 3 girl who broke rules and didn’t care what anyone thought. But that wild, bindaas girl also cared. She did get hurt. She just didn’t show it. It was expected of me to be the lively, bubbly one, and I played that role well — because it is a part of me. Last year, when I was putting out the book, I also went on stage with my stand-up in Delhi. Robbie Williams once said, “The funniest people are the saddest people.” I’ve felt the truth of that.

Owning your feelings isn’t depressing. If you’re still showing up for the people you love, you’re doing okay. And even if you don’t show up sometimes — that’s okay too. Humour gave me strength, it became my facade. One of my stand-up pieces is about how single women are seen as bad women — and I’ve lived that judgment. People have said unkind, untrue things about me just because I was single. That piece is about the pride of being a single woman. Humour and pain have always walked together for me. Humour saved me. It protected me. It’s just one part of who I am.

Do you think being untamed — as you call it — is a choice, a rebellion, or something that just happens when you’ve survived too much to pretend anymore?

Again, it’s never just one thing or the other. First of all, it’s the nature of the beast. I was born like this. My father raised me to be equal to my two older brothers. I was the youngest, the only girl, but he’d say, “If they can do it, so can she.” My mother would worry — “It’s 11 o’clock, she’s still downstairs playing with the boys!” — and he’d say, “Her brothers are there too. It’s fine.” “She’s climbing the wall? It’s fine.” “She’s climbing a tree? It’s fine.” That was my dad. He never let me be boxed in. And I’ve carried that through life — into my career, my choices, everything. So yes, it started as nature. Then it became a choice. Then it turned into rebellion. And eventually, when life threw enough at me, all the rest just fell away. The masks, the pretense — gone. There was no reason left to pretend.

Also, age teaches you that too. As you grow older, you see it more clearly. And especially in the last five years, the collective loss that we’ve lived through. The disasters, the wars, the grief. Where is the space for pretending? I feel it all. I absorb it all. And I’ve come to believe this: there’s no point in pretending anymore. I’ve survived, I’ve faced the worst and come out on the other side. I’ve made lemon juice from the lemons life handed me. The truth is right here, glaring at us — in the fires, in the earthquakes, in the wars, in the losses, in the silence of COVID. So really, what’s left to pretend about?

In your films you have played full-bodied, full-hearted women. Your poems too feel like an extension of that same honesty. Do you feel like you’ve been reclaiming what it means to be a woman in India — through your art, through your voice?

Honestly, it’s not about being a woman in India. It’s about reclaiming how to be me. I’m reclaiming my soul, my truth — who I was before the world got to me. Before it chipped away at me, changed me. That’s what I’m taking back first: myself. Over time, I’ve been building the courage to be me again — fearlessly. Without the fear of being disliked, misunderstood, or judged. There’s nothing left to justify. Nothing to defend. I keep saying this: I am who I was before the world got to me. Whether that means coming back louder or softer — I don’t care. What I do know is I’m not shrinking for anyone anymore. I’m not hiding. I’m not pretending.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated