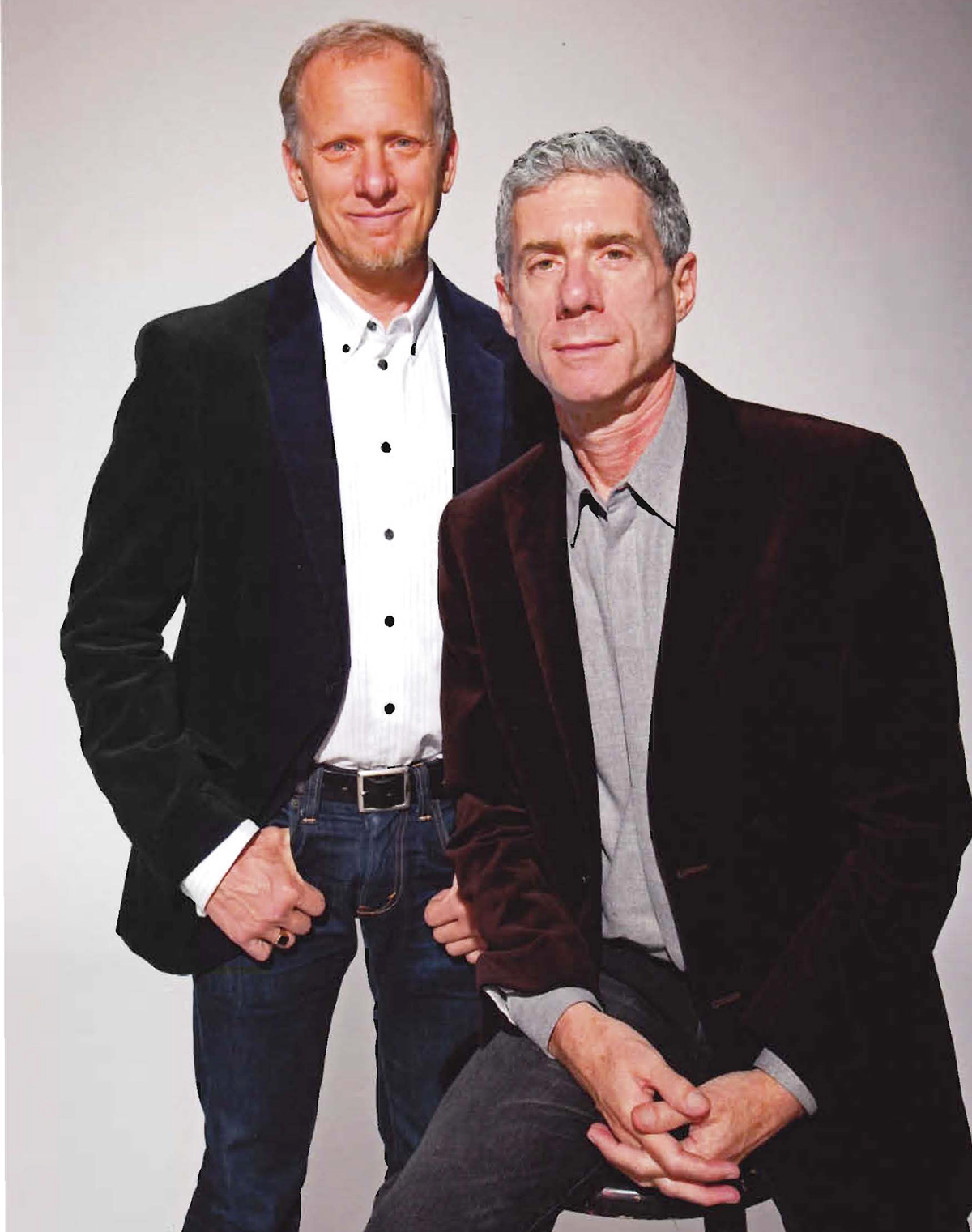

Rob Epstein and Jeff Friedman. Photo: Gene Pittman

A conversation with Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, among world’s most successful documentary filmmakers, whose latest feature documentary, State of Pride, is about LGBT rights movement

For more than thirty years, Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman have been among the most successful documentarists in the world. These two directors, producers, writers, and editors founded the production company Telling Pictures, based in San Francisco (https://www.tellingpictures.com/). The two Oscar prize winners devoted themselves to “groundbreaking feature documentaries”. In their hands, stories of poets, activists, politicians, heroes, and ordinary people reach a profound level that is at the same time ethical and aesthetic. This is the case, for example, in Common Threads. Stories from the Quilt (1989), depicting the story of the “NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt”, in The Celluloid Closet (1995), a journey through a century of homosexual characters in Hollywood movies, as well as in Paragraph 175 (2000), dedicated to homosexual survivors of Nazi concentration camps. We see this also in their production of Howl (2010), a movie on Allen Ginsberg’s scandalous poem, embellished by amazing animated textures, in Lovelace (2013), about the life of a pornographic superstar, and in their last feature documentary about the LGBT rights movement, State of Pride (2019). Through devotedly accurate historical research, Friedman and Epstein are able to glimpse deeply into personal stories that take history forward — moving from the “particulare” to the “universale” so to speak. Their documentaries go far beyond the gender question, and social developments triggered by the LGBT movement by dealing with human rights, humanity, death and transformations.

This interview was conducted in Zurich during the Pink Apple Film Festival 2017 (pinkapple.ch), and has been revised in collaboration with David Yetter after the release of their recent documentary, State of Pride (2019).

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: Jeffrey, Rob, I would like to ask you the “secret” of your ongoing, successful collaboration.

Rob Epstein: The secret? I don’t think there’s any secret, I don’t think there’s any formula.

Jeffrey Friedman: We trust each other, and we have been working together for a long time… so we have a sort of shorthand that we’re able to use. I think we both understand how our tastes are similar and where they diverge. So we are able to very easily communicate creatively.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: I’m impressed by the amount of research behind your films. For example, in your first film directed together, Common Threads. Stories from the Quilt (1989), you chose five of the 60 interviews to illustrate the complexity of the AIDS epidemic during the 1980s. I’m curious if your decision to concentrate on the documentary form was made at the beginning of your career or whether it has progressively developed.

Rob Epstein: I started out in documentary as an apprentice. Back then it was easier to get into independent filmmaking through internships and apprenticeships. That’s how I started and how I really learned about filmmaking. It involved just going through the ranks, through the editing process, the production process, and ultimately connecting with something on my own, and it was documentary. It was only in the later years that Jeffrey and I started working more in scripted fiction. First scripting non-fiction, and then fiction. The Times of Harvey Milk (1984) was structured more like a fiction film, which was probably a change from the more typical cinéma vérité-documentary. Same with Common Threads; at the time, we were making films that were more predetermined in their story structure and that was also reflected in the casting process. So, casting the five people was part of that whole map of putting the film together, which is a very different approach than letting the story evolve in front of the camera and then going along with that story as it’s evolving. To summarise, we didn’t start out intending to do narrative film, but always to do narrative non-fiction film.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: Rob, you stated that Common Threads was probably your most personal movie, because of your involvement with some people who appeared in the movie. AIDS was a social stigma, some victims did not even get a funeral because they were considered “abnormal.” Just a few days ago, Etienne Cardiles made a moving speech in memory of his husband, the police official Xavier Jugelé, who was a victim, together with three others in the recent terrorist attack [April 20, 2017] in the Champs-Élysées in Paris: “You will not have my hate. This hatred, Xavier, I do not have because it does not resemble you.” He then concluded: “I would like to tell you that you will stay in my heart forever. I love you. Let us all remain worthy, watch over the peace, and keep the peace.” This is an example of how attitudes and laws have changed, such as the new civil union legislation in Italy under Matteo Renzi’s administration. It is a lesson not only of dignity, but also a declaration of love that goes completely beyond the gender question that only a few years ago would not have even been possible. How much have art and cinema contributed to the liberation movement?

Jeffrey Friedman: I think that in order for film to have an effect on society it must expose society to things it wouldn’t normally look at, and to expose it in a way that’s meaningful and makes the point understandable. I don’t have any illusion that a film can have an immediate impact and change the world, but I think that the potential of film, fiction and non-fiction, and of all art is to make people feel and understand what other people are going through.

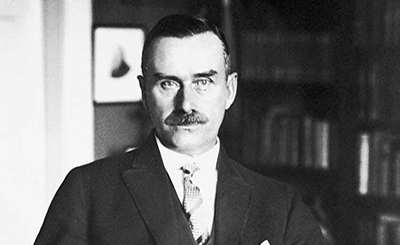

Rob Epstein and Jeff Friedman. Photo: Don Holtz

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: In this sense, your film The Celluloid Closet (1995) shows that to be gay in the Hollywood industry today is still not considered “normal”.

Rob Epstein: Society has changed, and movies are going to look pretty stupid if they don’t keep up with society and with societal changes. Younger people are growing up with gay friends, gay uncles, gay parents, and gay siblings. There will always be a segment of society that’s going to react against gays for whatever reason, whether religious, cultural, or other reasons. I don’t think things are going to go backwards in terms of how people are. Governments may respond differently, but at a certain point it seems the culture is just going to have to keep up with cultural change.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: I was thinking about how much these problems are still alive today. In these times of populism, new forms of religious thinking and legalism are increasing in our culture. How much in your view is this involvement of religion or religious interpretation still present in our society, despite all the steps forward in terms of human rights and acceptance of identities?

Jeffrey Friedman: It is very hard to generalize about where humanity is, perhaps just because we are so diverse. Really, it depends on where you are, it is very different in the cities than it is in the countryside or in small towns.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: Chechnya.

Jeffrey Friedman: In the United States it is very different from one part of the country to another, you know, Chechnya is certainly very different from Zurich or Paris. So, I don’t think we can generalize. Hopefully, the progress that is made in some countries will in some way translate to hope for other countries. People just have to progress at their own pace.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: Sure, and even if there are probably similarities in metropolitan areas, as in Paris where Marine Le Pen had only 5% support in the city, and similarly in the case of London and other big cities in the UK, where the vote did not go in favor of Brexit.

Jeffrey Friedman: Yes, look at Trump in the United States and everywhere, the same thing. I don’t know what’s going to happen. Right now I’m hoping that France will learn from our mistakes, and Britain’s mistakes. People are angry, and they don’t really know how to direct their anger. They don’t have a satisfactory outlet.

Rob Epstein: I think things are changing. Since reality TV and cellphones, everybody is a documentarian in a sense. How all that sorts out in terms of the art of it, I’m not sure. I think that we are in a kind of transitional time. The kind of work that we do and our peers do are more popular than ever. In large part that’s because journalism is suffering and is a dying industry, people don’t look to the news in the same way they once did, putting more faith in documentary coming from filmmakers than in journalism. It is a kind of heyday for documentary film makers in the United States right now.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: That brings to mind the impressive and courageous documentaries by Alex Gibney.

Rob Epstein: Yes, that is a prime example.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: Do you feel your particular documentary style or philosophy was inspired by certain authors or film makers?

Rob Epstein: I’m always looking for inspiration and different people inspired me for different reasons at different times. I don’t know if I can articulate a philosophy of our work. It certainly has a humanistic nature, how we tend to be interested in things that have to do with human behavior and what results from human behavior.

Jeffrey Friedman: Yes, I think that’s right. Our approach is to tell stories through personal experiences rather than tell political stories. When telling a political story, or a story that is in the news, the important thing is the experiences of the people who are living it. I believe that is at the heart of how we make films.

Rob Epstein: So the test for me in terms of art is whether it’s something that anyone wants to see again in ten years. In some films we’ve made, fortunately that is the case. In others, they have been much more disposable… there is no reason to see them again, they’re more fora-specific moment. Those tend to be more commissioned films, rather than the work that we produced on our own. And that is kind of what you have to do to survive, as a documentary filmmaker.

A still from Rob Epstein and Jefrrey Friedman’s State of Pride. Courtesy of YouTube Originals

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: The big questions of life and death are very important in your films. For example, in Paragraph 175 (2000) you enabled survivors of the Nazi concentration camps to speak to a large audience about their dramatic life experiences. And in Common Threads, one can see how individual cloth panels, commemorating victims of AIDS, came together, to form a huge quilt. It has been a collective ritual with an enormous impact. These narrations have to do profoundly with death. I’m wondering how you feel when viewing your work now years later, narrating chapters that for young people today are becoming things of the past.

Rob Epstein: That is my concern, that young people are not interested in these things. I don’t know if young people are going to film festivals in general. Maybe they’re going for the first time to see a film or to experience it as they did in the past. In talking with some attending the festival, I found the average age of those attending were people in their forties and fifties. This may be an indication of what young people think about cultural things like film festivals and retrospective film. That is both a question and concern I have, fearing history is not processed and internalized. Young people may not see that it is relevant to them. I can remember when I was coming of age, and anything about World War II made me think “what does War World II have to do with my life or with me?”

Jeffrey Friedman: Every generation thinks that it is the first to do everything, and that it is the most important, and nothing which came before is more important. I think this changes as you grow older and maybe that’s why the average age of those attending festivals is older. I think that young people will become interested in the reasons things are the way they are, and how we got here.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: Maybe that is a way for young people to understand their parents or older friends, and that’s really important.

Rob Epstein: It is also important to find a way to preserve these works. It is hard, because as formats and technologies change, many are discarded. Preservation is important for historical films, so they remain available for young people to see when they’re ready.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: I found the soundtrack of Paragraph 175 amazing for its elegance, discretion and lack of pretention. It allowed the possibility, and created space for these people to speak. How do you choose the music for your films?

Rob Epstein: I started working with score for the first time on The Times of Harvey Milk, and I had no idea, what I was doing at the time, but I saw another documentary that used original music. It wasn’t very typical, especially because documentary purists were only using music only as source material within a scene. For Harvey Milk, there was a piece of music that was an inspiration, the soundtrack of The Battle at Algiers, by Ennio Morricone. Sometimes you have a piece of music in your head, and with each of the films we’ve had a theme used to set the tone and the composer to work with it from there. I don’t have a musical background, Jeffrey doesn’t either, so it is hard to articulate. So often you find something that approximates the tone, which serves as a conversation starter with the composer. We have yet to meet Tibor SzemzÅ‘, the composer who composed the music for Paragraph 175. It is really all to his credit. I was thinking the same thing while recently watching the film, that the music is just spectacular.

Jeffrey Friedman: It was a collaboration between him and our editor, who took Tibor’s music and rethought it, using it in ways we hadn’t thought of originally. Once you have the music and you put it against the pictures, everything changes. It is a very delicate process, you don’t want the audience to feel that the music is manipulating or giving cues as to how you are supposed to feel while at the same time it should lead the audience to feel, right? It is always a collaboration, I think, between the filmmaker, the composer, and the editor.

Rob Epstein: Péter Forgács is the name of the Hungarian filmmaker whose films introduced us to Tibor SzemzÅ‘. Péter Forgács does found-footage style films, where SzemzÅ‘ did the soundtracks. We used SzemzÅ‘’s music as temp on Paragraph 175.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: During the interview, one of the concentration camp survivors said that he never really spoke of his experiences. Among the aims of psychotherapy today is to connect with the force of memory and to articulate the trauma, enabling a kind of narration. You made this possible, so to say, for both the survivors and the audience. While everyone does not feel the emotion to the same degree, it’s important to present.

Jeffrey Friedman: Yes, it is a beautiful thing when people are enabled to tell their stories, and for people who are helped by hearing them, creating a sort of catharsis.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated