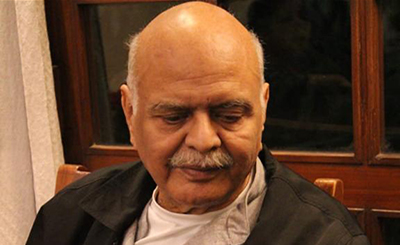

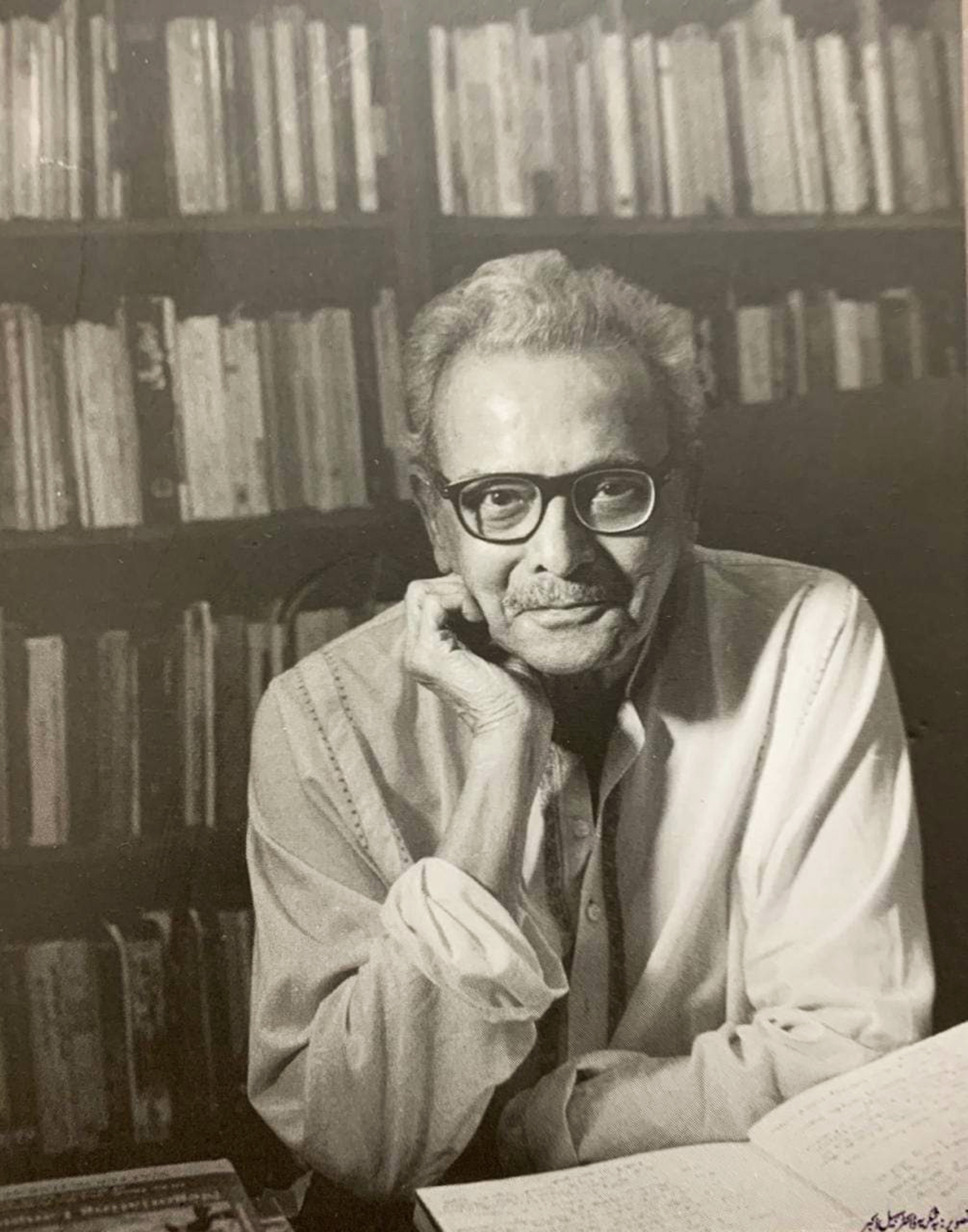

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi. Photo courtesy: SRF family

The second segment of a two-part interview with the veteran Urdu critic, writer, poet and theorist, who passed away on December 25. In this interview, he looks back on his life and times, and literature. Read the first part here

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi: You asked me whether my experiences and my feelings of the times of the freedom struggle, when Indians were striving for self-management and many were also foolishly seeking to divide the country into Hindustan and Pakistan… You asked me whether these experiences of mine, these tensions, these thrills and disappointments, went into my work anywhere.

Susmita Srivastava: Yes? Perhaps at a later date?

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi: The answer is no. The reasons are very complex. In fact, it is a very good question. It made me stop and consider those early days of seventy years ago and more and why I, consciously or unconsciously, did not reflect those things, those passions and those moments, in my work in some way or other. Last night, I stayed awake thinking about it. It’s a difficult question to answer, particularly seventy years on, but what I recollect strongly… of course, we all know that memories, especially childhood memories, are very deceptive and things that we are ready to swear happened may not have happened, so that should be taken as a given… but there are certain things which I don’t describe with my memory of events but my memory of what I thought at that time. For example, my father’s family were Deobandi maulanas, they were either apolitical or they were favourable towards the Congress. My father’s elder brother was an active member of the Jamiat Ulema which was more or less the Deobandi Maulana wing of the Congress. They supported the Congress all the time and everywhere, practically without reservations.

My father had an open mind. He admired Gandhi. In fact, he taught me to appreciate Gandhi’s English, the way he expressed himself. He admired Nehru for his elegance, for his speech, for his writing and for his message. He admired Jinnah because of his elegance and because he was always very well turned out, like an Englishman. He admired Maulana Azad because of his religious knowledge and his nationalistic thought, which is to say thought which was in favour of keeping India undivided and which opposed the Muslim League or any other power that supported partition. For example, in the early days, the Communist Party of India also supported partition. The RSS and the Hindu Mahasabha also harboured the feeling, sometimes expressed, sometimes unexpressed, that they would prefer to ‘let the bastards go away. Let them take a little piece of India and leave so that we have the rest of it for our own’.

On my mother’s side, my maternal grandfather was active in the Muslim League. He was very influential in Banaras; he came from an influential family there and retired as a very senior officer in the UP government. He also contested the election on a Muslim League ticket and won. I used to see a number of Muslim League leaders coming and going in my parents’ and my grandparents’ houses, especially during the days of the Cabinet Mission, 1946. I remember that Ramzan fell right in the middle of summer that year, 1946, in May and June, and we all…although I was only twelve or perhaps younger…we all were fasting but, to a man, none of the Muslim League leaders who came to see my father had kept the fast. So we had to feed them, offer them cold drinks, and I used to hate it! (Chuckles). I found them arrogant: at least to me they seemed so. Against that…of course, I never had the occasion to see, far less meet, Abul Kalam Azad…but I once attended a Jamiat Ulema conference in Azamgarh with my father. We were sitting very near the dais and we saw Maulana Hizbul Rehman, a famous leader of the Jamiat Ulema who later became an MP, a very prominent religious leader and also politically active on behalf of the Congress. So my father says, “Salaam karo inko.” I said salaam alaikum and he answered with such a beautiful smile and such a kindly expression on his face… I’ve written about this in one of my autobiographical notes. Not only was I completely bowled over by his gentle, kind face and smile but it also occurred to me that no Muslim League leader would be so gentle and so friendly and so kind to me if I greeted them. But then there were lots of conflicting emotions because I could see that a big segment of the Congress was anti-Muslim. It was seen as anti-Muslim and it was anti-Muslim, even then. It was not as if it became anti-Muslim later on due to exigencies of politics. Even at that time we could see that they had certain agendas, sometimes open, sometimes hidden, which were not favourable to Muslims. Not in an active sense, but certainly in the sense that they seemed to favour Hindus rather than Muslims.

I admired Mahatma Gandhi; I admired, in fact, envied the people who took part in the 1942 Quit India movement. I had no qualms in admiring even those people who inflicted carnage at the Chauri Chaura station near Gorakhpur, who set fire to the police station. I did not at all dislike them, I thought this happens, they are revolutionaries. This is what they want to do. I admired Bhagat Singh, I admired Ashfaqullah Khan. I was in favour of Khudi Ram Bose and Chandra Shekhar Azad, whoever I came to know of in that small town. That time was highly political, everybody had a political opinion and political interests. It was a big quandary for me. I saw, and I felt it strongly, that no Muslim League leader ever went to jail whereas Congress leaders were often in jail. I remember my father admired the collection of letters that Abul Kalam Azad wrote from prison in Ahmednagar to his friend. Of course, they were not published at the time, in fact, they were never even meant to be sent. So, they were a kind of conversation with a friend or monologues with himself, about life and the world and literature… nothing about politics. So, Dr. Syed Mehmood was there, Abul Kalam Azad was there, Nehru was there…a number of people who were imprisoned in Ahmednagar fort. I also tried to read that book a little bit. It was difficult for me to follow but still… Because my father admired the book, he kept it with him by his bedside all the time and I could see that here was a great man, Abul Kalam Azad, terribly self-confident and learned, and with a certain passion for certain things, like history, literature, Islam, nationalism, and India. I was terribly conflicted. I didn’t like Muslim League in that sense but I could also see that there was some reason for it to demand the Partition of India. Of course, later on, I came to know why the Cabinet Mission Plan and the Simla Conference failed. I was not so mature then as to read the English papers and understand the niceties of it but I didn’t want it to fail. But it happened.

So, on the whole, these things were right here, in my mind and in my heart, but at that time I didn’t have the tools to express myself, you see, about them. Like my hatred of the Nazis, for example. I remember I cut out a small photo of Hitler and pasted it in my magazine with the caption, “Duniya ki Khaufnaktareen Hasti” (The Most Terrifying Entity in the World). In 1945, when the Germans surrendered and Hitler was supposed to be killed, an English newspaper published a cartoon showing Hitler in a coffin being taken to be buried, which also I cut out and pasted in my magazine.

Susmita Srivastava: Were you aware, at that time, that there was a section of Indian society which actually supported Hitler, as the enemy of the enemy?

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi: No, but I did know that Subhash Chandra Bose supported him, or anyone, for that matter, who was anti-British. I knew that Netaji was very active in the Indian national struggle, that he left India, that he formed the INA which consisted of both Muslims and Hindus and that he went and met Hitler. All those things I knew and I saw nothing wrong in it. At that time, I saw nothing wrong in Subhash Chandra Bose collaborating with Germany and Japan except that I felt that somehow they were not the right allies for us because if the English were to leave India, these people were unlikely to become our friends and advisors, they might even become our rulers. Nothing very distinct, but I had some anxiety… this feeling actually came from reading a lot of propaganda literature against the Nazis, against Hitler’s regime and the Stalinist regime, which the English brought out regularly: pamphlets, magazine articles, newspaper stories and so forth. In any case, I was prepared to condone violence, I was prepared even to approve of violence as it happened in 1942 and I actively supported in my heart Netaji and his seeking support from Japan and Germany, but a certain feeling was there that Muslims don’t feel quite at home in this country. It was not so much the Hindu-Muslim killings in 1946-47 that affected me as things that really happened in front of me. Because there was no rioting, if it was called rioting then. We have rioting now, which is just a euphemism for communal killing.

Susmita Srivastava: What did you see in front of your eyes?

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi: In early 1948, India was free and UP was ruled by the Congress party. Govind Ballabh Pant was the Chief Minister, Sampoornanand was the Federal Minister. There was a person called Srikrishna Dutt Paliwal. He was also a minister in the UP cabinet. In early 1948, he came to Azamgarh as a minister, invited by our school to address students. He came and his whole hour-long speech was nothing but a hate speech against Jinnah and Pakistan. I remember his words, “One of their parts is 2000 miles away and when Jinnah miyan tries to go there in his plane, we will stop him mid-way and lock him up.”

Susmita Srivastava: Why?

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi: Because he was Jinnah miyan, what else. The very manner in which he called him Jinnah miyan…There was talk in those days that the British would be obliged to award the Muslims a corridor from Lahore to Dhaka, through India. You can imagine the folly of those times. How long the frontier would be, who would guard it on both sides, how many people would be affected, nobody seemed to care about these things. But many thought that the corridor would happen. Not that I believed it. This was just talk, it was never meant to happen. No one put it up as a proposition in a conference, even. Anyway, in that context of that talk… I thought to myself, Mr Srikrishna Paliwal, you are a Congressman, you’re from what is supposed to be a secular, non-communal party, you are a responsible person, a minister in the cabinet and this is only a high school with children ranging from the age of 8 to 14, and you are telling them to hate Pakistan because you hate it so much, on grounds of religion, on grounds of separation. Had he said that it was wrong of Jinnah to ask for the Partition, to insist on a separate homeland, I would have understood. It would have been an argument. But to say that Jinnah miyan was something contemptible, a fugitive from his own country, India… for over one hour, he harangued and raved. I am sure the headmaster was surprised, if not shocked. I was shocked. I am here, I didn’t go to Pakistan, my people didn’t go to Pakistan, neither my paternal nor my maternal grandfather went to Pakistan.

For the full text of this interview, write to [email protected]

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated