Mirza Ghalib statue at Jamia Millia Islamia. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

An imaginary conversation with Urdu’s best-known poet — about the police brutality in Jamia Millia Islamia, CAA, Sedition, Shaheen Bagh, and much more — that flits between the past and the present

On December 15, 2019, two of my friends and I were part of an anti-CAA-NRC-NPR protest at Gate number 7 of Jamia Millia Islamia (JMI). Later, a suitably revolutionary moniker was created for this place and it came to be known as Jamia Square. From this Square, we, along with other protesters, trooped down towards Julena, where, we stayed for a good deal of time as other groups of students kept coming and becoming part of the march. Then, the protest set out for the next destination, but the police didn’t allow it to move beyond the Surya Hotel.

Therefore, it got stuck near the hotel for quite some time. Meanwhile, more and more groups of people of varied size converged there. Through the Sujan Mohinder road, people started moving towards Mata Mandir road to approach Delhi Mathura national highway. Since the Sujan Mohinder road was chock-a-block, three of us entered the Community Centre (CC), reached near the MTNL office on Mathura highway, took a right, and kept moving. Some police personnel were ahead of us carrying tear gas, and around half a dozen were behind us. We had just crossed the Indian Oil Petrol Pump when we heard the first shot of tear gas; however, we kept walking.

Two more tear gas were shot. We started feeling irritation in our eyes and throats. Two more tear gas were shot in quick succession. Then, we decided to turn back through the same route we had got there. We entered the Shaheed Abdul Hamid park that lies across CC, and arrived at the CV Raman thoroughfare that led us to Julena intersection where we saw a good number of students. A sense of uneasiness was palpable. Along with many other students, we kept walking on the Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar roadway. JMI is on either side of this particular road. First, we decided to enter the main campus (gate no. 7) but dropped the idea, given the fact that we no longer were students of the university. We saw four to five of Jamia’s security personnel at the gate who were checking students’ identification.

As we crossed the gate number 7, there was a stampede as the Delhi Police had started using batons and lathis on students. We rushed to Dr Zakir Husain’s mausoleum where we stopped to catch our breath. On reaching Jamia School, we saw a pall of black cloud rising into the sky. We were separated from one of our friends in the melee; he later gave me a call that he was on his way home. Two of us reached Tikona Park, had a cup of tea at Zahra, and decided to drag our tails home and come back to JMI sometime later. We got our homes, and only after forty-five minutes came to know through social networking sites and WhatsApp messages that the Delhi Police had gone berserk and brutalised students of the university.

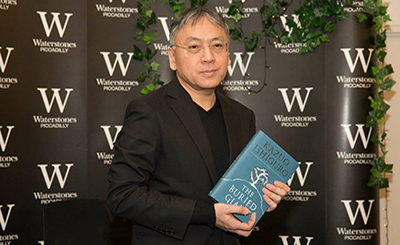

The statue of Ghalib standing in the middle of Gulistan-i Ghalib. Photo: Fahad Hashmi

Part II

On December 27, 2019, I went to my alma mater. The small and beautiful campus of Jamia wore a deserted look on this chilly winter evening. That particular evening, the sky looked as if it was suffering from conjunctivitis. I came across Mirza Asadullah Baig Khan, popularly called Mirza Ghalib, who was sitting on a marble bench in the middle of the park which is named after him. From a distance, Ghalib’s attire looked beautiful — “a white single-width pyjama, and a white muslin long tunic, open on the left side”. "On top, he wore a flowered lemon-colour cloak.” As I get closer to him, I realised that the cloak was slightly pale and smeared with dust and the lower end of cloak was slightly burnt. The silk dupatta that he used to tie around his waist was missing. His cap, kulah-ipapakh, was conspicuously absent. With his head shaven, white beard — neither too long nor too small nor too thick —looked dirty and disheveled, large eyes and smiling countenance, sunken cheek with almost no teeth (the front two teeth were clearly missing, with no molars on either sides), the bard looked crestfallen.

Since it was his birthday, I had purchased a nosegay, grapes (I do know that he is fond of mangoes but, alas, it’s winter in Delhi!), deep-fried imritis, and a silk fabric cummerbund from Mobarakpur.

I salaamed him in a low voice. He was staring at the Al-Beruni reading hall.

[Ghalib didn’t utter a single word for some time]

‘Ah! Mianaaphain.’On his left was seated his steward, Kallu, clutching a bag with both the hands.So, he seated me to his right.

I understood that he was not in the mood to talk. So, I asked his permission and his only reply was:

‘Ghalib’ hamen na chhed ki phir josh-e-ashk se

baithe hain ham tahayya-e-toofaan kiye hue

(Ghalib, don’t torment me — for again, with a turmoil of tears,

I sit here, well equipped for a typhoon)

Kallu took out sheets of pages from the bag and handed it to Ghalib. The poet started perusing the tract which must have been around 25-30 pages long. I mustered enough courage and asked: Does this contain your new ashars (couplets)? Endowed with a gift of repartee, he uttered in a harsh voice:

tujhe ath-kheliyan soojhi hain hum bezar baithe hain

(You seem to be in a playful mood while I’m a soul in torment)

Ghalib took sometime in soothing his anguished conscience, and later answered my query. “It is Dastambū. ’Out of curiosity, I asked him in a soft tone: Dastambū? But you wrote it long time back in the wake of rebellion of 1857 and the corresponding massacre that was unleashed on the inhabitants of Delhi. “Yes! Yes! That was written in 1858.”

The poet started reading Dastambū. I was attentively listening to every word. After listening to a few passages, my first impression was that it was some socio-political tract written for our times. It contained his contemplation on events taking place in Hindustan, rather “New India”. Moreover,it sounded a counter-narrative to the propaganda about the students of this university that they had indulged in violence on December 15.

In this Dastambū, Ghalib is mentioning every gory details of violence that looked scripted on December 15. He categorically named it: “Ides of December”, just like “Ides of March”. He mumbled, “Just look at the reading hall and the library. They have damaged it completely. Glasses shattered; CCTVs damaged; the whole library is littered with shards of glass, sleepers, torn books, notebooks.Desks and benches are scattered haphazardly. The campus is strewn with students’ blood and tears. It is haunted by their screaming, yelling, whining, and crying. More to it, the racial slurs hurled by the persecutors have left the students emotionally scarred.” In a rage, he said: “It was an attempt at assassinating the spirit of Jamia.”

[After an aggressive and painful cough, Ghalib recommences…]

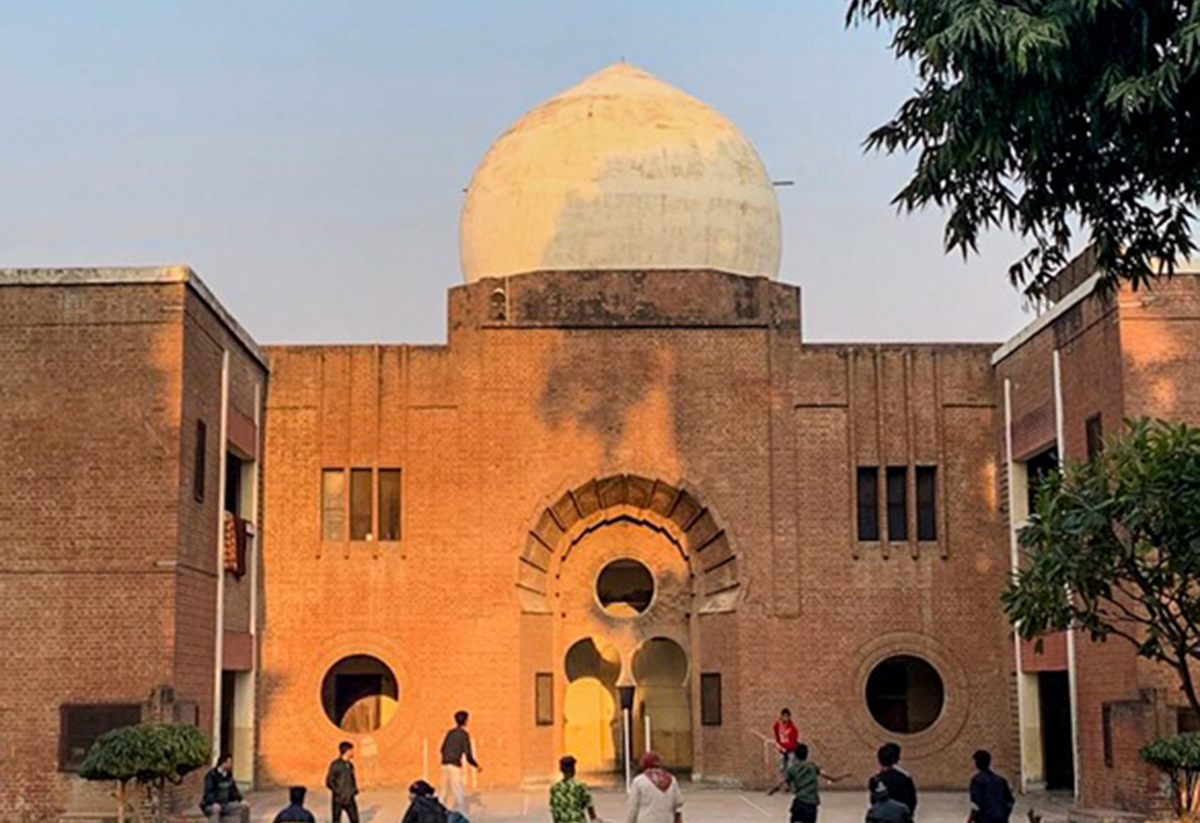

Don’t they know the history of Jamia and its role in India’s freedom struggle? Can’t they get the point that anti-imperialist writing is on the wall of this university, metaphorically as well as architecturally? Just glance at the buildings of the Jamia school and the education faculty! They neither resemble the British architecture nor the Mughal one. What was the name of that Austrian architect? ...Ya Khuda! Ye hafza kyun saath nahin deta?! Haan, the architect was Karl Heinz, if my memory serves me right.

These buildings used to be the Jamia School for a good deal of time. Much later, owing to space crunch, new buildings got constructed.The “old” buildings serve as hostels now. Photo: Fahad Hashmi

Ghalib told me that it is Dastambū II. Pointing towards the campus he waved his right hand like an arc and said:

kya, khoob qayamat ka hai goya koi din aur

(That’s rich! After this destruction could there be another doomsday?)

[Ghalib leans forward and begins again…]

Mahatma had rightly said about Jamia that it’s “like an oasis in the Sahara.”

Me: It’s still an oasis in the Sahara of illiteracy.

Ghalib: Will it remain so? (He asked rhetorically).

I thought he was weeping but later realised that chemicals of teargas — which hangs in the air over Jamia — had uncorked his old lacrimal glands. He was continually coughing and rubbing his red, bloodshot eyes. Kallu, in the meanwhile, silently informed me that Mirza Nausha used his sash as a bandage for wrapping up the wounded leg of a female student, and lost his cap when there was bedlam in the library.

Ghalib: Do you know I lost my kalam in 1857?...“I…never kept my verse with me. Nawab Ziauddin Khan and Nawab Husain Mirza collected and wrote down whatever I said. Both their houses were looted and libraries worth thousands which they contained were looted. Now I crave for my own verse.”

[The poet tries to catch his breath, and again starts saying…]

Don’t they know that a library is an index of civilisation? They have become so uncivilised! This is unbelievable! Are we going to see book-burning ceremonies?

Me: It is yet to be seen.

On the wall of JMI, a graffiti depicts a slice of brutality by Delhi Police on December 15. Photo: Fahad Hashmi

Voices Keep

Coming From

Some Distant Place

Hame chahiye Democracy!

Awaz do…Hum ek hain!

Bol re saathi halla bol!

NRC-CAA-NPR wapas lo, wapas lo!

Ghalib: The word DamanCracy is falling on my eardrum again and again? Ye kya bala hai?

[According to Ghalib, it seems, Democracy is actually Damancracy owing to the fact that minorities easily get persecuted in this form of government].

Me: (I corrected him) Democracy it is! A system of government — an American sadar has defined it — “Of the people, by the people, for the people.”

[The bard turned towards me, smiled a wan smile, and said…]

Ghalib: “Dil ke khush rakhne ko Ghalib ye khayal achha hai’

(To keep the heart happy, Ghalib, this idea is good)!

What is this public outcry over NPR-CAA-NRC?

Me: One needs to show khagaz (document) as a proof that s/he is a shahri (citizen) of this country. In other words, this is a programme for exiling Muslims in their own country.

Ghalib: How can they even think like this? Can’t they get illogicality as well as arbitrariness entailed in the political rationality of this qanoon?

What does it mean to send a Muslim into exile in her/his own country? Angrez sent Bahadur Shah Zafar to Rangoon. Where are they going to send us?

Me: Detention Camps

Ghalib: So, their intention is to commit genocide just like 1857 in their DamanCracy! What is this utter nonsense? If this be the case then let them put my name first in their first list. My ancestors came to this Hindustan from Oxus; Samarkand, more precisely.

[Ghalib shouted loudly]

hum khagaz nahin dikhayenge

(I won’t show the papers)

Ghalib: What do you think?

Me: About what? What do you mean?

Ghalib: Politics ke iss bisaat (chessboard) pe Shah ko maat (checkmate) kon de ga?

Me: Women and Students

Ghalib: I also think so. They have transformed highways and roads into Theatre of Pompey of our times.

Me: Bilkul sahi. Streets help people in countering “tedious argument of insidious intent” of regimes that run democracies across the world. Here, they condemn ruthlessness, inefficiency and arrogance of the folk in the driving seat of the state machinery. Streets, in a nutshell, work as a conduit through which grievances of the subaltern reaches to the corridors of power.

Ghalib: Are they going to review their stance?

Me: As of now, it looks quite impossible. But, wazir-e azam has said something contrary to Shah sahib.

Ghalib: Why are you so mistaken, janab? Faruqi has rightly written that Angrez were very kayiyan (cunning). The people of your DamanCracyis no better than those Angrez!

dete hain dhoka yeh baazigar khula

(These tricksters fool us openly)

The sorry state of Muslims in the Indian state of UP openly tells a tale that the government bears a rancour against Muslims. Stripped to its most basic, they have made Muslims an evil. The sarkar has unleashed police on Muslims, and they have become autocrat in their own right. Did you listen to victims’ testimony and the fact-finding teams’ report before the jury that was set-up by the People’s Tribunal on State Action in UP?

Me: Yes, I was present in that programme.

Ghalib: Horrible! Horrible!

[I got reminded of a passage from Ghalib’s Dastambū of 1858]

Today, every British soldier is an autocrat. While going from House to Baazaar the heart of a man fails him. The chauk is a slaughter house and my house is like a prison-hole and all of Delhi’s dust is thirsty of Muslim blood. Should we meet, we would complain of body, heart and soul. In anger we would complain of the fire of hidden wounds and we would weep and tell tales of weeping eyes.

Ghalib: Do you have some news from Agra? Is everything alright there? Mirza Tafta has written a letter wherein he mentions that there have been protests against this jalladi Act in Agra, too.

The firangi sipahi had looted jewellery of my begum in 1857, and the police personnel have stolen the jewellery of prospective brides in 2019!

Why are they so averse to Muslims? Where does this enmity spring from? How do they nurse hatred of such a great magnitude?... God knows! They should read Dastambū and my letters, too, to get an idea about the scale of loss of life and property of Muslims in 1857. Our sacrifice will be weighed in with papers of little worth! Hudd ho gayi!

Mirza Tafta has also written that they have killed 23 people in Uttar Pradesh, and also didn’t allow the body of Anas to get buried in a nearby cemetery.

Me: Bilkul sahi likha hai!

Ghalib: Hmm (His eyes are welled up with tears)

Me: What happened?

Ghalib: Yusuf yaad aa gya

(He said it with a heavy heart)

Me: Oh yes,he died in 1857.

Ghalib: No, he was killed in 1857.

Me: But you didn’t mention it in Dastambū.

Ghalib: Hmm. I have written that he died of high fever. You must take into account the reign of terror that was unleashed by Bartanvi hukumat as well as a culture of silence to get the point.

[His face reddened with rage]

“Monday, nineteenth of October, should be erased from the calendar. Like a fire-breathing dragon that day engulfed the world when in the morning the unfortunate darban brought the relieving news of my brother’s death.”

Me: kya hua thha?

[Ghalib snorted, and orally narrated a passage from Dastambū of 1858]

Ghalib: Oh, do not speak to me, I beg you, of water or of the kerchief to clean the face, of the man who bathes the dead body or digs the grave, or of bricks or mortar! Please tell me how I can go out (of this lane), where to take this dead body, and in what graveyard to bury it. In the bazaar it is impossible to get cloth, either good or bad. It is as if labourers and earth-diggers had never existed in the city. The Hindus can carry their dead to the shores of the river and burn them, but the Muslims dare not go abroad, even in groups of two or three, so how can their dead be borne from the city?

Me: Some people are of the opinion that your Dastambū was an effort to…

[The bard cut me short]

Ghalib: I can understand what you are driving at! Mind you, I remained “inwardly estranged but outwardly friendly” to the Empire. Haven’t you read my versified sikka after Zafar resumed full sovereignty in 1857? I know what you would ask me next. Miyan, it’s also not mentioned in Dastambū. But if anyone gets the chance of glancing over Munshi Jiwan Lal’s original Roznamcha, s/he will easily spot it there.

[The poet breathes fast while speaking this couplet]

sadiq hun apne qaul ka Ghalib, khuda gavah

kahta hun sach ke jhuut ki aadat nahin mujhe

(God is my witness, Ghalib is no liar;

I set great store by my integrity)

[After appropriate hiatus]

Me: What’s your opinion on the Ayodhya verdict?

Ghalib: ‘Baat niklegi to phir dur talak jayegi’…rahne dein! Mokhtasar ye ke…It was hard to stomach the judgement but we thought that ‘kahin to jake rukega safina-e-gham-e-dil’ (The boat of the afflicted heart’s grieving will drop anchor somewhere) but…

Me: Do you have any news from Kashmir?

G: Janab, I got a ‘Postcard from Kashmir’ last week, and the pain and humiliation is still unbearable.

[Ghalib moved to the corner of the park and started crying in the void]

‘Kashmir, Kaschmir, Cashmere, Qashmir, Cahmir, Cashmire, Cashmere, Cachemire, Cushmeer, Cachmiere, Casmir.’

[The poet sobbed, wiped out his tears, and returned back to us]

Ghalib: There is news making the rounds that a few writers from Deccan have been shot dead? Could you, please, confirm the news?

Me: The news is true but a bit stale. Gauri Lankesh, Govind Pansare and MM Kalburgi were murdered during the previous term of the current regime.

Ghalib: Maulvi Muhammad Baqar ki yaad aa rahi hai. We had strained relationship but that’s beside the point. He was a brave man! Hudson shot him dead for his anti-British writings. Fazl-e-Haq Khairabadi was also sent to Kalaapani and he died in exile. In Kucha Chelan, firangi forcibly took out Sahbai from his home and shot him, too. In that locality alone more than a thousand people were killed.

[After a painful cough, Ghalib asked]

Miyan, Sedition kya hota hai?

Me: Tauheen-e reyasat (blasphemy against the state)!

Ghalib: Samjha! The colonial state enacted 124-A of Indian Penal Code (IPC) for people associated with the Wahhabi movement. Angrez made Muslims innately violent and seditious. Kambakht Hunter spewed venom in his book Indian Musalmans that has sealed the fate of Indian Muslims forever.

[After a short pause]

Ye Sharjeel kon hai?

Me: Sharjeel is an azad-o-khudbeen (free and proud) guy who stated his political convictions with passionate intensity! He is being labelled ghaddar and desh-drohi by his enemies. A few people who have got vested interest in demonising Sharjeel are labelling him Musanghi.

Ghalib: Musanghi?

Me: Musanghi is neologism. In fact, it is a portmanteau word made-up by blending Sangh and Muslim.

Ghalib: Don’t you think that this portmanteau is a misnomer for Sharjeel? A Muslim who adheres to the ideology of Sangh could be called Musanghi like Shahnawaz and Mukhtar but Sharjeel…Khair…

[Ghalib loudly recited a couplet]

ḳhirad ka naam junun pad gaya junun ka ḳhirad

jo chahe aap ka husn-e-karishma-saz kare

(Sanity has been named madness; madness sanity.

Anything is possible, with your incredible ingenuity!)

[On hearing voices coming from outside the campus,

Ghalib looked a bit perplexed]

What is this hubbub on the road?

[He wanted to see it for himself. Ghalib extended both his hands towards me, chanting the couplet]

muzmahil ho gaye qava Ghalib

vo anasir mein e'tidal kahan

(All Ghalib’s powers are wasted now, and in decline

That eternal harmony has fled away)

He is hard of hearing but still managed to listen to the waxing and waning of voices of students chanting slogans, reciting inquilabi poems, guitar strumming, azaan from the nearby mosques, ballad of Amir Aziz, Sahil’s rendition of Italian anti-Fascist song Bella Ciao into vapas jao, Afaque’s speech, and a host of cultural activities outside gate number 7. He is impressed by the students’ enthusiasm.

Students enjoying cultural programmes outside gate no. 7 of Jamia Millia Islamia. Photo: Fahad Hashmi

Ghalib: These students remind me of Zakir, Mujeeb, Abid and Lohia. At Jamia, they had their first lesson in anti-British nationalism. That was jang-e-azadi first, this seems to be jang-e-azadi second!

After slaking his thirst and happily enjoying the protest for two-and-a-half hours, he cheerfully recited a couplet with full passion:

Is saadgi pe kaun na mar jaaye ai Khuda!

ladte hain aur haath mein talwar bhi nahin

(Who will not give up his life on this simplicity, O God!

They do all the fighting, without in the hand, even a sword)

[After rubbing eyes and coughing for a few seconds, the poet resumes…]

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated