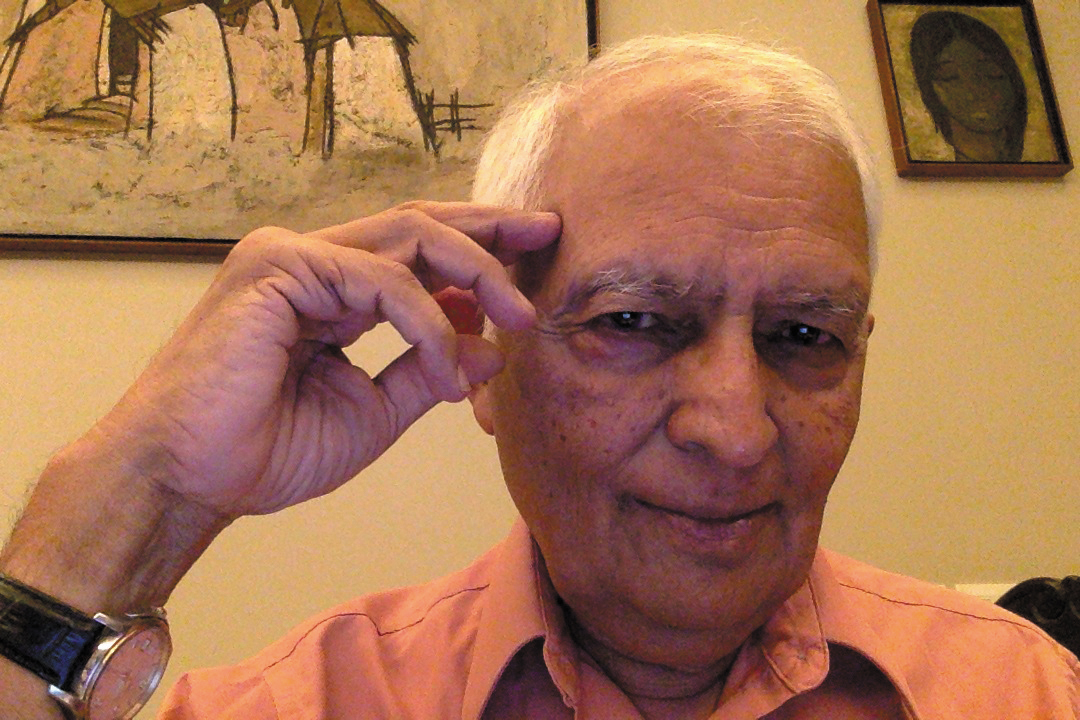

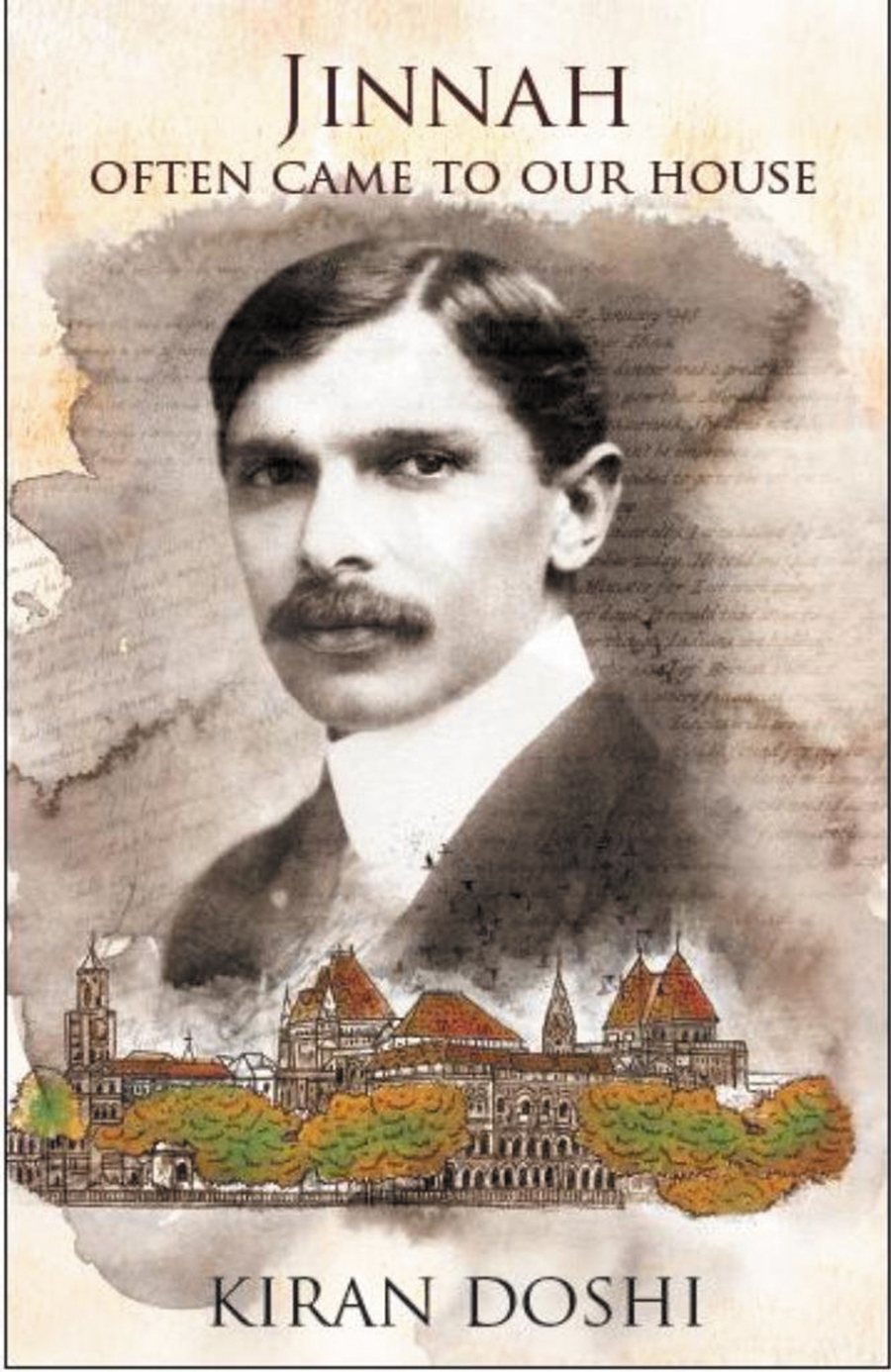

New Delhi-based retired diplomat, educationist and author Kiran Doshi is the winner of the 2016 Hindu Prize for his novel, Jinnah Often Came to Our House (Tranquebar, 2015), which was announced in January this year.

Doshi studied history, politics and law in Bombay before joining the Indian Foreign Service in 1962 for a 35-year-long career. He is the author of Birds of Passage, a novel set in the world of India-Pakistan-USA diplomacy, and Diplomatic Tales, short stories written in comic verse.

Jinnah Often Came to Our House, set amidst the long struggle for freedom and the call for Partition, is a heart-wrenching saga of love and betrayal, pain and redemption. Doshi, who is now working on a sequel to the novel, says the world would have been a far, far better place if Hindu-Muslim unity in India had not been torn apart, and India partitioned. “The novel, in large part, is an account of all that I learnt while trying to find an answer to the question: why Pakistan?” he says.

Excerpts from an interview:

THE PUNCH: Jinnah Often Came to Our House is an ambitious novel with a sweeping canvas. Tell us about its genesis. While it tells Jinnah’s story, it’s also a deeply felt lament against Partition and what it did to the two nations. What did you want this novel to be about when you were working on it? How important was it to tell this story in the tone you have chosen for the novel?

KIRAN DOSHI: Pakistan. A brief reply to the question on the genesis of the novel is the tragedy called Pakistan, tragedy for not just that country, nor even for just the entire subcontinent — and specially the Muslims of the subcontinent — but for the whole world. Yes, the world would have been a far, far better place if Hindu-Muslim unity in India had not been torn apart, and India partitioned. The novel, in large part, is an account of all that I learnt while trying to find an answer to the question: why Pakistan?

As for the tone of the language of the novel, right at the start I chose, sensing that the novel was likely to become epical in scope, to adopt the tone of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, that is to say, to keep it natural, letting the terrain determine its rhythms and variations, never forcing it, no matter what the temptation.

THE PUNCH: You dedicate the book to your mother-in-law, Umrao Baig, whose father was a contemporary of Jinnah. Many of her stories have made their way into the novel. Tell us something about the stories of Jinnah that she, and many others in your family, shared with you.

KIRAN DOSHI: My mother-in-law’s father (my wife’s grandfather) was a contemporary and a friend of Jinnah — and of many other public men of his time, although he was completely apolitical himself. In fact, the title of the book comes from what my mother-in-law once said: Jinnah often came to our house. Some of the words she used to describe Jinnah were ‘striking-looking’, ‘elegantly dressed’, ‘soft-spoken’, ‘fastidious’ and ‘arrogant’. She also said (obviously quoting her father, who too was a barrister) that Jinnah was a ‘brilliant’ advocate. Apparently, the admiration was mutual. When Jinnah left for London, seemingly forever, he placed his black coat on her father’s shoulders (according to family lore) and said: ‘Nobody deserves the coat better than you.’ Incidentally, my mother-in-law’s sympathies, when Jinnah’s marriage with Ruttie collapsed, were entirely with Ruttie. ‘Jinnah’, she said when we talked about it once, was ‘a cold fish.’

Happily, her mother (my wife’s grandmother) was still around when I met my wife. She had in her proud possession several yellowed newspaper clippings of her husband’s court cases, which she happily showed to anybody willing to look at them. Several of the cases in the novel are (slightly altered versions of) the ones in those clippings.

There are also stories in the novel told to me by other relatives, stories from the Khilafat movement, from the sad migration of Muslims to Afghanistan in search of Dar-ul-Islam, from the Quit India movement and its bloody suppression, from the Gandhi-Bose split and the INA, from the naval mutiny and from the Karachi of 1947.

THE PUNCH: In the acknowledgements, you mention Francis Bacon: “Truth is so hard to tell, it sometimes needs fiction to make it plausible.” How different would this story be if you had written a non-fiction? Did fiction give you space to mould the narrative into the shape you wanted this story to take?

KIRAN DOSHI: There is an ocean of non-fictional books on the freedom struggle and its twin, the struggle for Partition. If I had written the book as non-fiction, it would probably have got lost in that ocean. In any case, once I realised that Pakistan was created by Jinnah (falling for the British trap as early as in 1909), I had to write on the young Jinnah, and, considering the great paucity of dependable information on the subject, I had to imagine what he must have been like. I may add that even non-fictional books on him use so many qualifiers (‘perhaps’, ‘undoubtedly’, ‘quite possibly, ‘would most likely have’, ’would have surely’...) that they can quite truthfully be called part-fictional. I chose straightforward fiction.

Yes, fiction also gave me the scope to add flesh — and much more than flesh — to the story. But, I hasten to add, as far as the historical part of the novel is concerned, it is faithful to what I believe happened.

THE PUNCH: Has Jinnah been misunderstood in India? Do you think after Partition he has been demonised?

KIRAN DOSHI: Yes, he has been demonised in India — and in fact in the world generally (except, of course, in Pakistan) but not because he has been misunderstood. On the contrary, the post-1937 Jinnah has been correctly understood in India. What is not clear to most Indians is how and why he became a tool of the British? Was it deep-rooted communal prejudice? Was it some terrible early experience? Was it just plain foolishness? Was it ambition thwarted? Was it some other Shakespearean flaw in his character? Jinnah Often Came to Our House seeks to give what seems to me the most likely reason — or reasons — for the path he chose.

THE PUNCH: Considering the sensitive nature of the novel’s subject and themes, did you have some caveats at the back of your mind while working on it?

KIRAN DOSHI: Only one, that in every non-fictional paragraph of the book, in fact in every non-fictional sentence, I must always tell the truth (naturally as I saw — and see—it.) I am aware that in recent years everybody and every event connected with the twin struggles (for freedom and Partition) has been subjected to fresh scrutiny by ‘experts’. I have chosen what, deep down, I feel to be the real story of the struggles.

THE PUNCH: How central was Sultan Kowaishi’s story to the rise of Jinnah as a face of the Indian National Congress? Did you have to work on the novel’s detailing?

KIRAN DOSHI: The fictional part of the novel is not only intricately interwoven with the historical part all though the years (1904-1948) but also alters with it, staying languid when the other is languid, picking up pace when the other picks up pace, turning tense, turbulent, tragic… in tandem with the other.

THE PUNCH: Let’s also talk about the other characters: Dhondav and Rehana. What roles do they play in the overarching narrative arc?

KIRAN DOSHI: Several of the fictional characters, relationships, and happenings in the book are allegorical. These include the characters of both Dhondav and Rehana, as well as their relationship with each other. I would like it to leave it to the reader to work these out, should he/she feel inclined to do so. (For the author to reveal what they represent would be to remove one of the many enriching layers of the novel, leaving it that much poorer.)

THE PUNCH: Did you have to work a lot on the novel’s structure? How important was to keep the narrative linear, with chapters divided according to the year?

KIRAN DOSHI: No, I had little difficulty with the structure of the novel. I suspect I am a linear thinker. Certainly, I find it somewhat unsettling to read historical novels that jump back and forth across time zones.

As for giving the chapters subtitles of time, my principle objective was to keep the reader constantly aware that the ‘story’ of the novel is interwoven with history. The dates are also intended to help the reader to better navigate through the crowded years of the struggles.

THE PUNCH: Tell us something about the techniques you employ in the novel — the use of both fact and fiction, letters and newspaper column, etc?

KIRAN DOSHI: There are really dozens of what people call techniques that I have employed, consciously or otherwise, in writing the book (humour, suspense, Shakespearean quotations, native proverbs, apt dialogues ...) several of which are used commonly by most experienced writers, but also some uncommon ones. Let me describe a few of these below:

Empathy with the fictional characters: Remembering what Flaubert said when asked who he had modelled his Madame Bovary on (Madame Bovary? C’est moi!), I tried hard, while writing the novel, to put myself in the shoes of every character, male or female, old or young, generally (even if I say so myself) with success.

Use of allegory: Most of the important characters in the novel (bari phuppi, Samiullah, Sultan, Rehana, Dhondav, Griffiths, Quinn, Mussal-manav, Firoz, Mariam, Nirbhav, Major Majid, Kashmira ...) and many of the events (Rehana’s school being named Ekta; Madhav dying in Amir’s arms at Jallianwala; the star-crossed Hina-Dhondav relationship; the rescue of Kashmira ...) are allegorical.

Keeping historical characters credible: While there is a lot of interaction in the novel between fictional and historical characters, and even between only historical persons, no historical person is shown as acting out of character (as known to history.) Moreover, the historical or real characters are only shown saying or doing things, never thinking things. There is no ‘Jinnah thought’ or ‘Gandhi guessed’ etc in the book.

Nobody in the novel, historical or fictional, is shown as having any inkling of the future. So, although the reader knows that the narrative is hurtling towards the abyss of 1947, he/she remains glued to the seat, wanting to know what happens next.

Use of letters: Sending letters regularly (and, telegrams occasionally,) even to people who lived in the same town, was the norm among educated classes in India in early 20th century. Used in novels, letters can serve to express emotions that leave a far greater impact on the reader’s mind than spoken words (eg., Mariam’s last letter to Rehana.)

Two special characters: What also helps to make the novel richer is the presence of two major fictional characters: Mussal-manav, the anonymous writer of politically incorrect thoughts (like in modern-day blogs); and Pandey, who brings to life the young, ambitious Jinnah in the earlier chapters, and describes the dilemmas of the older Jinnah in the later ones.

THE PUNCH: What were the best books on Jinnah and Partition you read while researching the book?

KIRAN DOSHI: While there are a number of books on Jinnah in English (by Wolpert, Bolitho, Jalal, Jaswant Singh, Mathews, Noorani...) none of them was particularly useful for writing Jinnah Often Came to Our House. The reason for that is simple. The books say little of Jinnah’s early life, and so of the inner man. Jinnah himself never kept a diary, did not leave behind any memoir and was extremely reluctant to talk about his private life in his letters. I had to construct the inner man with the help of every morsel on him that I could garner from all sorts of books, newspaper articles, the internet ..., even Pakistani blogs, guarding myself all the while against the dangers of either demonising or deifying the man.

As for books on the Partition, I did not really need to reread them while writing the book — all my life I have been a student of Indian history —except to check up details (dates, places, exact spellings, exact texts ...) of speeches and events that I considered relevant enough for inclusion in the novel.

THE PUNCH: You had a 35-year-long career in Foreign Service. Looking back, could you share some of its exciting and frustrating aspects? How do you view the state of Indo-Pak ties today?

KIRAN DOSHI: To describe aspects of the Foreign Service, I wouldn’t know where to begin. A 35-year career, spanning thousands of people, places and problems, leaves behind a Mahabharata of memories in one’s mind.

As for Indo-Pak ties, in essence they are exactly where they were in 1947, or even before. And I much fear that they are not going to change for the better for many, many years to come, unless something dramatic and unforeseeable happens.

THE PUNCH: What are you currently working on?

KIRAN DOSHI: A sequel to Jinnah Often Came to Our House, built round Kashmira (Rehana’s granddaughter) and Rehana herself. I am also working on a collection of mainly comic short stories. (My first love is short stories; Diplomatic Tales, my second major work of fiction, was a collection of short stories, albeit written in comic verse).