Illustration by Sam Wallman

Sam Wallman’s poignant graphic journalism in “At Work Inside Our Detention Centers: A Guard’s Story”

Not so long ago, on a day like any other, I was strolling through the endless maze of the internet and I chanced upon a stark and compelling black and white web comic titled “At Work Inside Our Detention Centers: A Guard’s Story”. This 2014 verbal-visual text, illustrated by Sam Wallman, has travelled extensively and rapidly across the virtual terrain and garnered eyeballs and thumbs up from across the globe since its publication in The Global Mail1. In an age of unprecedented mobility, it is ironical that this narrative allows us a peek into a glaring contradiction afflicting our hypermobile world. What we witness through Wallman’s creation is a staggering force of immobility imposed upon numerous asylum seekers from a variety of conflict zones held up in Australian immigrant centers.

This graphic narrative is a hard-hitting journalistic enterprise exploring a pressing and contemporary field of injustice. It gives life and form to an anonymous guard’s testimony regarding his experiences in one such detention center. It documents the debilitating effect of practices of power and curtailment on the immigrants. Having fled from extremely traumatic conditions back home and having made their way to Australia through perilous journeys, these migrants, finally washing up ashore, drained and gasping for comfort, are met with renewed insensitivity and persecution. This poignant piece of graphic journalism incrementally reveals a tragic picture of many of the indefinitely detained individuals in Australia’s immigrant centers. Along with this, it also registers the parallel toll felt on the guard as he becomes a witness to this spectacle of inhumanity. What comes through then, is an intertwined psycho-scape of seemingly two opposing entities of the ‘immigrant’ and the ‘native’ both hurtling down into an emotional abyss, taking also, the reader/viewer along with them.

Through its powerful art work and sparse but sharp textual accompaniment it manages to touch upon both macro politico-economic forces orchestrating this enterprise, as well as the micro psycho-corporeal effects of the ordeal. And it is probably owing to its aesthetic choices that it performs the role of much more than a mere informative piece and carries in it strains of a complex insight and statement of protest.

Visual Framing

The element of Wallman’s visual code that stands out most prominently is the ample use of negative space, sometimes within, but often around the illustrations. Instead of the customary frames, vast white blankness envelops the images of incarcerated travelers and their variegated cages. The lack of conventional visual containers triggers a number of reflections in the viewer.

Firstly, though the piece itself represents an articulation, it also emphasizes a deep and heavy silence around such tales. The thick blank spaces, weighing upon the whole text, serve that purpose. While our mobile feeds are full of stories threatening us of a global refugee crisis, painting a picture of the world that is on the move like never before, this frontier phase of systemic and often ruthless movement control is buried under a layer of oblivion. In fact, stories like these are a rare and daring exception to the ordered silence around the maltreatment of needful asylum seekers at the behest of stringent and paranoid state policy. And quite clearly, so much is left to be investigated and expressed. So much yet remains beyond our sight and comprehension.

The blank margins also suggest a process of decontextualisation of a heterogeneous group and their complex migration patterns. State authorities, media as well as locals tend to classify them into a blanket category that may go by various tags, often tilting towards the pejorative kind. “Boat people” or “queue jumpers” are some such examples commonly encountered in the Australian context. The narrator of Wallman’s text, notes how the other staff members of the detention center are completely oblivious to the difficulties that these men and women held up in the centers have undergone. In fact they have deluded themselves to believe that the ordinary folk they are dealing with day in and day out, with force and indifference, are in fact dangerous, law breaking, “illegals”. Thus, the white-washing of their histories almost seems like a convenient cognitive act to ease their conscience and execute their job.

More importantly, the bracketing of the art work with blank space contributes to a feeling of suspension, a suspension both in space and time, much like the status of the detained immigrants. The location of these immigrants remains hanging in between political and discursive frontiers, the liminal space between the hostile homeland and the unwelcoming Australian threshold (good point!). Their citizenship, in fact their very validity as human beings, seems somewhat suspended. This feeling of suspension is expressed not only through the sweeping white space surrounding the visuals, but also through more direct images, like the bulky structures of the training and detention centers. They appear to be yanked from the surface of the earth and frozen mid-air.

In one memorable sequence of images we see three inmates digging graves for themselves in the volley ball court of the center. This court also seems to be a mass of earth, detached and floating in space. With feet dangling in the grave, a few rudimentary crosses fixed into the ground, and stars and celestial bodies peeping from inside the graves, these people seem to be inhabiting a modern day purgatory, hanging between two worlds, in a state of almost eternal waiting for any kind of release to come their way.

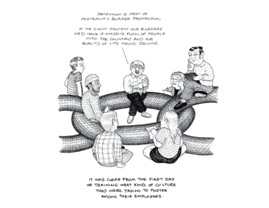

Apart from a feeling of suspension, the lack of frames creates other kinds of illusions too. In one image, in the employee training center, we see the instructor sermonizing to the new employees about the necessity of Australia’s border protection from “the massive flow of people threatening the country’s standard of life”. Wallman places the bunch of men and women on a gigantic chain while this discourse is on and they are, as if, in the process of learning how to man the ends and edges of their great nation. Ironically however, in spite of this enlarged motif of boundaries, the whole panel itself is borderless/frameless. This panel seems to me a much-needed critique of the illusion of openness and borderlessness in today’s so-called transnational world. The heart of the matter remains that our nations, like our other identities, are steadily taking a fiercely territorial turn.

Another motif, through which the simultaneous hypermobility and territoriality of the modern world comes through, is embodied by the Serco corporation. The text proclaims that the service provided by this multinational company cuts across multiple geographies and yet, paradoxically, the services it does provide clearly buttress territorial power in its various forms (warfare, state surveillance, immigration inflow control). The nature of multinational capitalism then appears rather distorted, moving in an increasingly tightening spiral of sorts.

This constant juxtaposition of enclosure and open space, boundaries and borderlessness, also speaks to me of Foucault and Deleuze’s discipline and control societies respectively. Perhaps it is not that Deleuze’s modern, mobile and expansively networked and monitored society has replaced Foucault’s older enclosed disciplinary structures, but that both kinds are simultaneous in their operation.

Verbal/Discursive Framing

Apart from the echoes emanating from its visual framing, this text also points to a faulty system of verbal framing that surrounds the refugee situation. As professed by the narrator and etched by the artist, the sanitary terminology of ‘immigration centers’, and ‘transit centers’ is nothing but a flimsy discursive veil to hide incarceration camps and prisons. Though their labels imply a certain amount of protection, service and legal process, their cage-like, barred-windowed, suffocating concrete structures tell a different story altogether.

Similarly, we are made aware that the inmates are to be addressed as ‘clients’, a word reeking of market capitalism and implying a degree of agency, equality and reciprocity. Thus, the term becomes absurd when placed in front of images of individuals, carrying marks of trauma, and whose very gaze seems to have been drained of all purpose and will. The trainer goes on to reveal, in fact, the absurdity of these labels that are not in any way intrinsic to this group of people but violently superimposed on them by ‘departments’, media, and political currents. Thus, the way they are verbally framed by ruling structures is the way we begin to perceive them. And, consequently they are perceived by such centers fundamentally as ‘detainees’, who are to be treated not very differently from criminals undergoing punishment. Thus, a vulnerable group is criminalized through popular discourse, putting these already brittle lives at further risk.

Proliferation of Lines

While we noted the lack of traditional grids in the comic, the use of lines is ubiquitous in the text. Horizontal, vertical, diagonal and labyrinthine lines play a variety of roles. We see them as imprisoning bars, as deep fissures and cuts. We see them as thresholds to crossover, as well as fences to bar. We sometimes see them as ties that connect the strange mix of detainees in spite of their trying circumstances. At other times they take the form of dark entangled knots of past journeys and trauma. And sometimes they even become threatening symbols of death. Lines in Wallman’s graphic narrative simultaneously carry a banality and an ominous fatality, their power of bridging as well as imprisonment. And thus, this visual buffet of lines of all shapes and forms seems to cover the vast psycho-political field in which the refugee is embedded, as witnessed by the narrator.

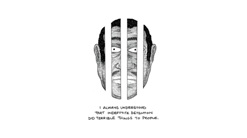

The text opens with a pair of sequential images of a man’s floating head (first seen frontally, later in a slight profile) hollowed out in-between by the white imprisoning bars of “indefinite detention” that not only seem to entrap him, but are drawn as if they have penetrated the very material and psychic makeup of these inmates, transforming into deep dismembering lesions.

This intertwined motif of the line as a constrictor and a wound is seen once again etched in a wide horizontal sketch of an outstretched arm, full of gashes and slits (a common sight, the text informs us, among the doubly traumatized refugees in these centers) The cuts on it almost extend from and seem to be manifestations of cartographic borders. The detained refugee’s body rightly becomes “the material site over and through which boundaries are contested and shaped” (Nabizadeh 172). This image of a limp, bruised, bleeding arm, unshaken and unreceived by the gatekeepersof Australia, not only displays the searing impact of stringent territorial regulations on individuals embodies the bio-political strategies that are a crucial method of gate-keeping and nation-building.

And, of course, there are those lines that tourists, businessmen and media cross over effortlessly. But the clearly demarcated ambit of the acceptable border crossers and the unacceptable border crossers lays bare the hypocrisy of a transnational claim of the 21st century which produces and reproduces disparity. Mobility then is a privilege that is granted to a select few, aptly called the kinetic elite, who can neatly and erectly step over boundaries that become for them welcoming, however monitored, thresholds. Whereas those who are the focus of this graphic narrative, the immobilized others (national/racial/socio-economic) so to speak, find themselves marked, trapped and contorted out of agency by these borders and remain locked in a powerless liminality. Their movement, if any, has been transformed into a futile and resigned circularity within the confines that contain them.

The Unwhole Body

The bodies that we confront in this text are found in varying degrees of contortion, fragmentation, hollowness, suspension and limpness. At every corner vulnerable bodies of the inmates — bleeding, bruised, and stooped — are waiting to walk into us. As a juxtaposition to these entrapped bodies of the immigrants, the easy circulation of the employees of Serco in an in almost infinite loop is striking. However, they too are not required in their wholeness as individuals, but merely productive bits of them. A brain to indoctrinate with an otherising discourse and arms strong enough to grab and restrain potential miscreants seem to be the bare qualifications for these men and women, men and women who are mere cogs to run this assemblage of control.

It is, however, this one guard who, due to his empathic vision, is able to see the brutality of it all and, towards the end of the narrative, begins resembling the inmates himself, in his listless stance and gaze. We see the gradual toll that the encounter with this frontier world takes on his relationships and his sense of self. He finally escapes this suffocating space, but seems to carry the marks of his experience on his psyche long after. The web comic, however, ends on a muted note of hope. As the guard shuffles along the vast open space of a supermarket/shopping mall, with eyes downcast, he happens to glimpse, astonished and overwhelmed, the two Rohingya men he often saw back in the center. Wallman ends his story with the close up of the floating heads of the two men, and one disconnected palm of each waving back at the guard, a repetition of their earlier image from the center, but this time in a different space and different light, and with eyes slightly restored in their vitality and a hint of a smile at the corner of their lips.

1. The Global Mail was a Sydney based, not-for-profit multimedia website that was in operation from 2012-2014. It mainly engaged in long form, investigative and project based journalism.

2. Nabizadeh, Golnar. “Comics Online: Detention and White Space in “A Guard’s Story.”Ariel: A Review of International English Literature. Volume 47, Numbers 1-2. Pp.337-357. John Hopkins University Press. 2016

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated