Hindu cremation grounds in Mumbai. Images courtesy of the author.

The virus is indiscriminate. It’ll affect you as much as it’d affect me. If today it’s our displeasure that all we can do is await the extinguishing of agony an infected patient suffers from, I’d like to imagine our rites to not be geared for what happens to the body after you die, but what you do with it when you’re alive

Author’s Note: For a major part of the coronavirus pandemic, I heard scores of instances where families couldn’t be united with the bodies of their loved ones after their deaths. People were scared to venture to hospitals — you didn’t particularly come out unscathed all the time from the OPD wards. And if you were diagnosed with the virus, chances were slim (at least initially, anyway) that you’d make it.

So, in this atmosphere, how were we to accord the final rite of respect to our dead? Our religions are foundationally built on the idea of rebirth, and to that end, we have scores of elaborate rituals that ‘aid’ in the passing of the soul to the next life. But when we can’t provide them this, how are we to grasp death? How are we to grieve with this sullying feeling of denial, when all our age-old traditions are now at the hands of a doctor and how (if) respectfully the body is disposed to the crematoria? In this essay, I argue, through a Mughal miniature and a Stoic’s philosophy, that maybe we’ve to take a different look at how we grieve today. If those chants and traditions were geared for life after death, we’ve to quite possibly rework them to find them applauding life before death. It is meekly blasphemous, and only a suggestion, but for all our dead, still something more resolute to hold on to, to remember by.

***

Reading A K Ramanujan’s ‘Annayya’s Anthropology’ is an exceptional treat. Annayya, a student at the University of Chicago, is a well-read individual; in his quest for self-knowledge, he’s always driving parallels with the life he once lived in Mysore, against what he reads in the university library. He’s always questioned about the peculiarities of Indian customs that Westerners fail to understand, and innocent questions like ‘why do your women wear that red dot on their forehead’ simply make him read more about Indian traditions. Chancing upon the anthropological work ‘Hinduism: Custom and Ritual,’ Annayya notices a scene regarding funerary rites. In a horrifying twist, however, he realises the study is being done in his own house in Mysore. Standing beside the pyre is his mother’s figure; the body on the pyre, his father’s.

It was an academic pursuit for the anthropologist, but for Annayya it couldn’t be more devastating — a crucial filial duty to perform was robbed from him because of the distance between Chicago and Mysore. I imagine today our predicaments are no less than Annayya’s.

In my measly existence of twenty years, I’ve found myself at the crossroads with death on three junctions: in novels and texts, in a Mughal miniature, and with an idea of Stoics. Do I call myself grateful that I haven’t physically encountered death? Beyond the existential dread of every post-millennial, I’d say yes. Do I count my blessings that I haven’t witnessed death among my near-and-dear? I’d nod solemnly. Six months living in social exclusion, however, and today death feels like sitting on my windowsill — not knocking, and if you can believe it, not mocking.

Every religion has had its version of the origin story; every religion has its share of dealings with judgment day. For several centuries, Hinduism has had scores of didactic narrations guiding us on how to approach death, and it is hardly a matter of simply paying our respects in white. One finds all things conceivable: from well-defined rituals to distinct methods of cremation and dispersal of ashes. So what happens when one is miles apart from the cadaver, when those final moments of goodbye are robbed from us, when age-old traditions are wiped away in one illegible scribble of a doctor’s diagnosis?

Does that make us fear death more? It is an inevitable fact that sooner or later our mortal bodies will wither away. That is a chilling thought, yet thankfully it mostly occupies the margins of our daily existence. Yet at times it also surfaces onto our puny existence. Whether it’s learning about someone’s demise or having a brush with it yourself — the winds of fate tend to blow everyone away. Death then isn’t a fleeting thought; rather, it’s an experience. When Carl Sagan said, “Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us...” it not just allowed astronomy to humble our tiny presence in the universe, but filled us with dread, asking,

‘Is that all that we are? And if that’s all that we are, what’d it be when we’d not even be that?’

For several million, the Rig Veda provided ease. Death was imagined to be an interlude till you would be propelled, reborn into your next life. For this was the Antyeshti rite of passage or the last sacrifices to be performed. The body was only a vehicle in a particular life-cycle; its soul, a microcosm in the macrocosm of the universe, was eternal. The proper release of this soul to the primordial elements that made life — air, water, fire, earth, and space — meant peace for the dead.

Over time, various admissions were made to the rite — from specifying if the big toes needed to be tied to piercing the burning skull with a stave to making a hole for releasing the spirit — our spirits were calmed with this proper deliverance. As the coronavirus pandemic set in, however, scores of instances emerged where the dead were hastily disposed of from the hospitals to make room for more patients. A sullying and terrifying notion to even imagine, yet all one could do was wait until the doctors informed of the death, and that was that.

How would one grieve, then? Do we gnash our teeth, wail inconsolably, or swallow our misery? How do we make peace when we can’t even afford the one final rite of comfort? Allow me to propose an exceptionally rare instance from the court of the Mughal emperor Jahangir, to attempt an answer.

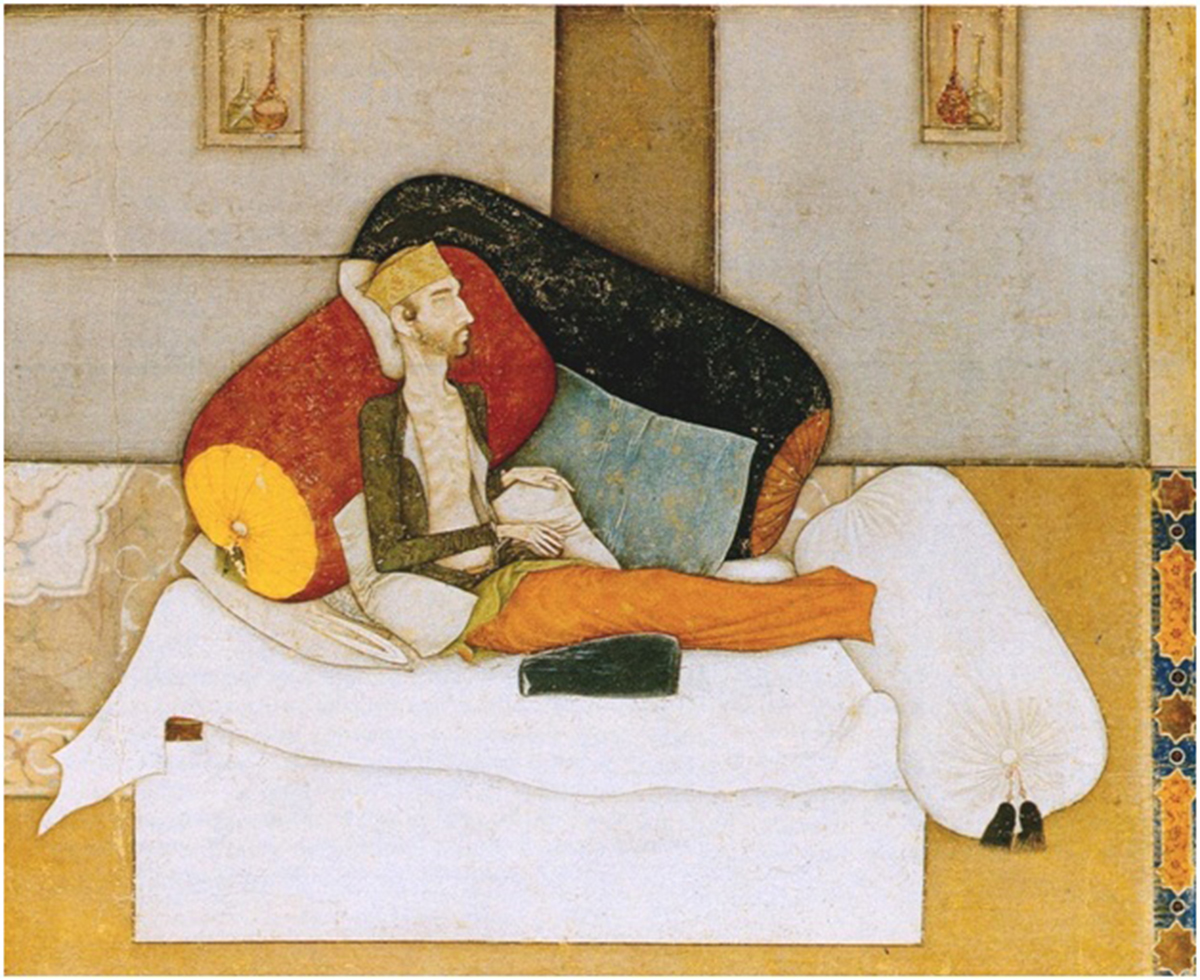

The art of Mughal portraiture was solely reserved for symbols of power, laid with allegorical themes of the court and the sovereign. What wasn’t the norm, was depicting the dying. Balchand’s The Death of Inayat Khan is perhaps the only example, and that’s not why it’s significant.

Balchand’s The Death of Inayat Khan.

Inayat Khan was an intimate companion of Jahangir, who made him the paymaster of the imperial cavalrymen. Alcoholism and opium addiction were to be this man’s final call; in 1618, Jahangir recorded his death. Upon hearing of his infirmity, Jahangir ordered his men to bring Inayat to his court, which they did on a palanquin. The following lines from the Jahangirnama best exemplify his state:

He looked incredibly weak and thin. “Skin stretched over bone.” Even his bones had begun to disintegrate. Whereas painters employ great exaggeration when they depict skinny people, nothing remotely resembling him had ever been seen. Good God! How can a human being remain alive in this shape? The following two lines of poetry are appropriate to the situation: If my shadow doesn't hold my leg, I won't be able to stand until Doomsday. /My sigh sees my heart so weak that it rests a while on my lip.

Inayat Khan’s emaciated grace could not go amiss. Yet what catches the eye is his comportment, the manner in which he presented himself in court. Inayat Khan is dressed in proper court attire for his rank, and presented in a seated, dignified manner with textiles, carpets, and bolsters keeping his frame stable. This is quite certainly in line with the concept of adab, or the genre that typified social conduct and rules of observance for the elites.

What I understand, however, is Inayat Khan’s last vestiges of augustness greeting imminent death. What his presence encapsulated wasn’t just respect for the Emperor, but respect for death — a formidable presence, no doubt, but one that wouldn’t matter after it exhumes him — so for what occasion otherwise would he keep his priceless clothes and rubies? Again, Jahangir best exemplifies what I wish to highlight:

...I said, “At this time you mustn’t draw a single breath without remembrance of God, and don’t despair of His graciousness. If death grants you quarter, it should be regarded as a reprieve and means for atonement. If your term of life is up, every breath taken with remembrance of Him is a gold opportunity. Do not occupy your mind or worry about those you leave behind, for with us the slightest claim through service is much.”

If the philosopher Thomas Nagel observed that death is the great deprivation, Epicurus vehemently argued that it’s not. It is Epicurus’ idea that I wish to give credence to.

I mentioned earlier about death being an experience; it most certainly isn’t, in fact. Let’s look at it this way — if you’re asked today to imagine what it’d be like if you were dead, what would you think of? Keeping aside the idea of rebirth, you’d imagine nothing. Death is an absence of being, and how do you imagine something that’s not? For the Stoics, it was folly to weep for the dead. There was an ineluctable course Mother Nature took, and it was futile reacting to something that wasn’t in control.

I agree, being a Stoic isn’t necessarily a good cup of tea, and I’m not even suggesting to drink it — rather, it’s not my place. What I’m merely musing at is taking a sip from it, for the fact of the matter remains that the virus is indiscriminate. It’ll affect you as much as it’d affect me. If today it’s our displeasure that all we can do is await the extinguishing of agony an infected patient suffers from, I’d like to imagine our rites to not be geared for what happens to the body after you die, but what you do with it when you’re alive.

Inayat Khan didn’t get a grand burial — in fact, aside from Jahangir’s writings, we have absolutely no clue as to what happened to his body. And yet, beyond his dying visage, lies the opulence his portrait reminds us of — of life, of living.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated