Ingmar Bergman. Photo: Wikipedia Commons

2018 marks the birth centenary of Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman (1918-2007), arguably the last great European auteur. A tribute to the master of psychological dramas whose world existed under the precipice separating dreams and reality and who considered films to be fragments of dreams

“The dominant, all-powerful factor of the film image is rhythm, expressing the course of time within the frame,” wrote the great Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky (1932-1986) in Sculpting in Time (University of Texas Press, 1989), in which he writes about art and cinema, with a focus on his own films. Filmmaking, for Tarkovsky, known for haunting cinematic poetry, is “sculpting in time” and the title of his book refers to the filmmaker’s own name for his style of filmmaking. Tarkovsky believed that the unique characteristic of cinema as a medium was to “take our experience of time and alter it”.

In Sculpting in Time, Tarkovsky talks about his “distaste” for the growing popularity of rapid-cut editing and other devices that he believes to be contrary to the “true artistic nature of the cinema”. By using long takes and few cuts in his films, Tarkovsky aimed to give the viewers “a sense of time passing, time lost, and the relationship of one moment in time to another”.

“The director’s task is to recreate life: its movement, its contradictions, its dynamic and conflicts. It is his duty to reveal every iota of the truth he has seen — even if not everyone finds that truth acceptable. Of course an artist can lose his way; but even his mistakes are interesting provided they are sincere, for they represent the reality of his inner life, of the peregrinations and struggle into which the external world has thrown him. (And does anyone ever possess the whole truth?) All debate about what may or may not be shown can only be a pedestrian and immoral attempt to distort the truth,” Tarkovsky writes in the book, which has a commentary on each of his seven major feature films — Ivan’s Childhood (1962), Andrei Rublev (1966), Solaris (1972), Mirror (1975), Stalker (1979), Nostalgia (1983) and The Sacrifice (1986) — as well as his complex relationship with the Soviet Union which had a bearing on his concise oeuvre.

Art As A Meta-Language

Tarkovsky emphatically saw cinema as a medium equipped to answer the myriad questions life puts forward. Art, for him, was “a meta-language, with the help of which people try to communicate with one another; to impart information about themselves and assimilate the experience of others.” According to Tarkovsky, the hardest thing for the artist is to “create his own conception and follow it, unafraid of the strictures it imposes, however rigid these may be.” He writes, “I see it as the clearest evidence of genius when an artist follows his conception, his idea, his principle, so unswervingly that he has this truth of his constantly in his control, never letting go of it even for the sake of his own enjoyment of his work.”

The filmmaker, who preferred to express himself metaphorically, believed that an image possesses the same distinguishing features as the world it represents. “An image — as opposed to a symbol — is indefinite in meaning. One cannot speak of the infinite world by applying tools that are definite and finite. We can analyse the formula that constitutes a symbol, while metaphor is a being-within-itself, it’s a monomial. It falls apart at any attempt of touching it,” writes Tarkovsky.

Art, the filmmaker feels, is born out of an ill-designed world. “The artist exists because the world is not perfect. Art would be useless if the world were perfect, as man wouldn’t look for harmony but would simply live in it,” he writes. Tarkovsky saw true artists as “prophets with a gift of prescience”.

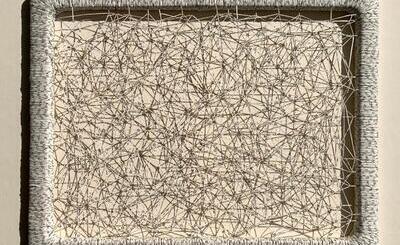

An Oneiric Universe

All of Tarkovsky’s films have a common theme: spiritual and metaphysical crisis. His films are characterised by extremely long takes and exceptionally beautiful images, with dreams, memory, childhood, running water, fire, rain, reflections, levitation, and characters re-appearing in the foreground of long-panning movements of the camera acting as recurring motifs. “Juxtaposing a person with an environment that is boundless, collating him with a countless number of people passing by close to him and far away, relating a person to the whole world, that is the meaning of cinema,” Tarkovsky once said.

A still from Andrei Tarkovsky's surreal film, Mirror

With his supernatural imagery, Tarkovsky creates an “oneiric universe teeming with life’s mysterious forces”. In Mirror, which best defines his vision as a filmmaker, an iconic dream sequence of the mother levitating above a bed as water cascades indoors is sublimely magnificent and one of the memorable scenes in the history of world cinema. Mirror unfolds with the associative logic of a dream, picking up fragments from the filmmaker’s own childhood, interspersed with his father Arseny’s poems. If Mirror is autobiographical and personal, Andrei Rublev straddles two worlds: historical and personal. While the film spans the epic sweep of Russian history, it was still highly personal for Tarkovsky in its “meditation on the risks and salvation of artistic endeavour”. With an emphasis on Christianity’s role in Russian identity, the film is based on the life of the titular 15th-century Orthodox icon painter (played by frequent collaborator Anatoli Solonitsyn) and shows how a leap of faith offers hope for spiritual regeneration. Set in medieval Russia, a brutal world of vicious rivalries and torture, treachery between princes and Tatar raids, it is the story of a bellmaker’s son who attempts to cast a massive cathedral bell under threat of death if he fails.

In a 1962 interview, Tarkovsky argued, “All art, of course, is intellectual, but for me, all the arts, and cinema even more so, must above all be emotional and act upon the heart.”

The European Auteur

If Tarkovskian cinema was sculpted in time, for Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman (1918-2007), arguably the last great European auteur, whose birth centenary is being celebrated this year, films were like fragments of dreams, slices of human psyche that transcended space and time.

If Tarkovsky believed that art, above all, must be emotional, Bergman, to a great extent, used “art as institution” as a metaphor for his more pressing theme of the lack of communication between people. Art and artists appear to provide Bergman with a device for exploring the “interplay between people” in general. In Bergman’s films, art is among three recurrent institutions — the other institutions being religion and the family — even though each serves a similar purpose in the larger scheme of things.

If, for Tarkovsky, the meaning of cinema boiled down to relating a person to the whole world, for Bergman it was about connecting a person to his inner self, his soul, his existential angst, his anxieties and apprehensions. Bergman’s characters struggle to find out whether life offers mercy and meaning. “I want very much to tell, to talk about, the wholeness inside every human being. It’s a strange thing that every human being has a sort of dignity or wholeness in him, and out of that develops relationships to other human beings, tensions, misunderstandings, tenderness, coming in contact, touching and being touched, the cutting off of a contact and what happens then,” the filmmaker was quoted as saying in Ingmar Bergman Directs by John Ivan Simon (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972).

A still from Ingmar Bergman’s Through A Glass Darkly

Incidentally, Bergman was part of a very exclusive pantheon of auteurs Tarkovsky admired, with others being French director Robert Bresson (1901-1999), known for his minimalist style of filmmaking, and Japanese master Kenji Mizoguchi (1898-1956), whose work stood out for long takes and mise-en-scène. Tarkovsky and Bergman shared a common vision and their admiration was mutual. “Tarkovsky for me is the greatest [of us all], the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream,” Bergman said in one of the interviews.

For Bergman, when film is not a document, it is dream. “That is why Tarkovsky is the greatest of them all. He moves with such naturalness in the room of dreams. He doesn’t explain. What should he explain anyhow? He is a spectator, capable of staging his visions in the most unwieldy but, in a way, the most willing of media. All my life I have hammered on the doors of the rooms in which he moves so naturally. Only a few times have I managed to creep inside. Most of my conscious efforts have ended in embarrassing failure,” Bergman writes in his first biography, Laterna Magica (1987), which was translated into English as The Magic Lantern: An Autobiography by Joan Tate (University of Chicago Press, 1988).

Early Years

In The Magic Lantern, Bergman also writes in detail about his childhood and adolescent years and his early fascination with cinema. Bergman was born in Uppsala, Sweden, to Erik Bergman, a Lutheran minister and later chaplain to the King of Sweden, and Karin (née Åkerblom), a nurse. He grew up with his older brother Dag and sister Margareta, surrounded by religious imagery and discussion.

Bergman’s father was a conservative parish minister with strict ideas of parenting. Bergman was locked up in dark closets for “infractions”, such as wetting the bed. “This form of punishment lost its terror when I found a solution. I hid a torch with a red and green light in a corner of the cupboard. When I was shut in, I hunted out my torch, directed the beam of light at the wall and pretended I was at the cinema,” Bergman writes.

While his elder brother was rebellious and unable to protect himself from his raging father who used all his willpower to break him, his little sister was the apple of their parents’ eyes and she responded with “self-effacement and gentle timidity.” Bergman writes: “I think I came off best by turning myself into a liar. I created an external person who had very little to do with the real me. As I didn’t know how to keep my creation and my person apart, the damage had consequences for my life and creativity far into adulthood. Sometimes I have to console myself with the fact that he who has lived a lie loves the truth.”

Most of Bergman’s upbringing was based on such concepts as sin, confession, punishment, forgiveness and grace, “concrete factors in relationships between children and parents and God”. He writes, “There was an innate logic in all this which we accepted and thought we understood. This fact may well have contributed to our astonishing acceptance of Nazism. We had never heard of freedom and knew even less what it tasted like. In a hierarchical system, all doors are closed.”

Other “infractions” had other punishments — “swift and simple.” Bergman writes: “The immediate consequence of confessing was to be frozen out. No one spoke or replied to you… After dinner and coffee, the parties were summoned to Father’s room, where interrogation and confessions were renewed. After that, the carpet beater was fetched and you yourself had to state how many strokes you considered you deserved. When the punishment quota had been established, a hard green cushion was fetched, trousers and underpants taken down, you prostrated yourself over the cushion, someone held firmly on to your neck and the strokes were administered. I can’t maintain that it hurt all that much. The ritual and the humiliation were what was so painful.”

After the strokes had been administered, the “sinner” had to kiss Father’s hand, at which forgiveness was declared and the burden of “sin” fell away, “deliverance and grace” ensued. “Though of course you had to go to bed without supper and evening reading, the relief was nevertheless considerable,” writes Bergman, who, early on, devoted his interest to the church’s “mysterious world of low arches, thick walls, the smell of eternity, the coloured sunlight quivering above the strangest vegetation of medieval paintings and carved figures on ceilings and walls”. He writes, “There was everything that one’s imagination could desire — angels, saints, dragons, prophets, devils, humans.”

Although raised in a devout Lutheran household, Bergman later stated that he lost his faith when aged eight, and only came to terms with this fact while making Winter Light in 1962.

Faith Matters

Winter Light (1963) is the second in a series of thematically related films, often considered as a trilogy, following Through a Glass Darkly (1961) and followed by The Silence (1963). Through a Glass Darkly, starring Harriet Andersson, Gunnar Björnstrand, Max von Sydow and Lars Passgård, portrays the struggle of a young woman, Karin, (Andersson) with schizophrenia having delusions about meeting God, who appears to her in the form of a monstrous spider. The film reconciles the belief in God with human suffering. Winter Light explains the metaphor when Pastor Tomas, played by Björnstrand, relates the “spider god” to suffering, as opposed to his previous ideas of a “God of love” that provides comfort.

A still from Ingmar Bergman’s Winter Light

Winter Light is the story of Tomas Ericsson (Björnstrand), pastor of a small rural Swedish church, who has to deal with an existential crisis and his Christianity. On a cold winter’s Sunday, Ericsson performs service for a tiny congregation; though he is suffering from a cold and a severe crisis of faith. After the service, he attempts to console a fisherman (Jonas Persson) who is tormented by anxiety, but Ericsson can only speak about his own troubled relationship with God. A school teacher (Maerta Lundberg) offers Ericsson her love as consolation for his loss of faith. But Ericsson resists her love as vehemently as she offers it to him.

While consoling Jonas, Ericsson embarks on a monologue, expressing his crisis of faith. When he was a seaman’s pastor in Lisbon during the Spanish Civil War, he says he refused to see the brutalities. “I refused to accept reality. My God and I resided in an organised world where everything made sense. I’m no good as a clergyman. I put my faith in an improbable and private image of a fatherly God. One who loved mankind, of course. But me most of all. Do you see, Jonas, what a monstrous mistake I made? An ignorant, spoiled and anxious wretch makes a rotten clergyman. Picture my prayers to an echo-God who gave benign answers and reassuring blessings. Every time I confronted God with the realities I witnessed, he turned into something ugly and revolting. A spider God, a monster. So, I sought to shield Him from life, clutching my image of Him to myself in the dark,” says Ericsson.

If there is no God, would it really make any difference? Ericsson asks himself and then answers: “Life would become understandable. What a relief. And thus death would be a snuffing out of life. The dissolution of body and soul. Cruelty, loneliness and fear. All these things would be straightforward and transparent. Suffering is incomprehensible, so it needs no explanation. There is no creator. No sustainer of life. No design.”

The pastor tells Jonas, “We live our simple daily lives, and atrocities shatter the security of our world. It’s so overwhelming and God seems so very remote. I feel so helpless. I understand your anguish but life must go on.”

Towards the end of the film, Algot, the handicapped sexton, questions Ericsson about the suffering of the Christ. Algot wonders why so much emphasis was placed on the physical suffering of Jesus, which was brief, versus the many betrayals he faced from his disciples, who denied him, did not understand his message, and did not follow his commands, and finally from God, who did not answer him on the cross. “I feel he was tormented far worse on another level… Christ’s disciples fell asleep. They hadn’t understood the meaning of the last supper or anything. And when the servants of the law appeared, they ran away… They abandoned him down to the last man. He was left all alone. That must have been painful. To realise that no one understands. To be abandoned when you need someone to rely on. That must be excruciatingly painful. But the worst was yet to come. When Jesus was nailed to the cross, and hung there on torment, he cried out. God, my God, why has thou forsaken me? He cried as loud as he could. He thought that his heavenly father had abandoned him. He believed everything he’d ever preached was a lie. In the moments before he died, Christ was seized by doubt. Surely, that must have been his greatest hardship: God’s silence,” says Algot. The pastor agrees.

Towards the end of Winter Light, Marta wonders as the service bell rings, calling out to the believers: “If only we could feel safe and dare show each other tenderness. If only we had some truth to believe in. If only we could believe.” A pensive Pastor listens in, rising to start the service at an empty church: “Holy, holy, holy is the lord of the Hosts. The whole earth is full of his glory.” And then he fades out. Is God’s glory of no help when it comes to human suffering? Bergman leaves you wondering.

Elsewhere, God is referred to as “a mocking reality”. In The Seventh Seal (1957), which is considered a classic of world cinema and one of the greatest movies of all time, a disillusioned medieval knight, Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) plays a game of chess with the personification of Death (Bengt Ekerot), who has come to take his life. “Is it so terribly inconceivable to comprehend God with one’s senses? Why does he hide in a cloud of half-promises and unseen miracles? How can we believe in the faithful when we lack faith? What will happen to us who want to believe, but can not? What about those who neither want to nor can believe? Why can’t I kill God in me? Why does He live on in me in a humiliating way — despite my wanting to evict Him from my heart? Why is He, despite all, a mocking reality I can’t be rid of?” wonders Block in the film.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated