Michael Ondaatje. Photo from the author’s Facebook page

Reading Michael Ondaatje’s Warlight is like walking through a blanket of fog and mist, with light surfacing at the end

“Our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness,” writes Nabokov in Speak, Memory, his memoir which was published in 1951.

Nabokov writes about his colossal efforts to distinguish the faintest of personal glimmers in the impersonal darkness on both sides of his life. “That this darkness is caused merely by the walls of time separating me and my bruised fists from the free world of timelessness is a belief I gladly share with the most gaudily painted savage. I have journeyed back in thought—with thought hopelessly tapering off as I went—to remote regions where I groped for some secret outlet only to discover that the prison of time is spherical and without exits.”

Writers have long excavated memory to explore the links between their self and their past. Remembrance, and forgetting, has been literature’s lifeblood. Often, the act of writing is, in essence, the remembrance of things past. The mound of memories that the writers mine, however, is slippery, with the writers’ outlook and approach being constantly shaped and reshaped by their understanding of the world. Stendhal, and later, Flaubert and Proust, were all aware of the fitfulness and ambiguity of memory, its elusiveness when we try to snare it. Memory's inaccuracy and its unreliability, however, only reflect the arbitrary division between fact and fiction.

“In probing my childhood (which is the next best to probing one’s eternity) I see the awakening of consciousness as a series of spaced flashes, with the intervals between them gradually diminishing until bright blocks of perception are formed, affording memory a slippery hold,” Nabokov writes in Speak, Memory.

Past, as L.P. Hartley wrote in The Go-Between, is a foreign country: They do things differently there. Hartley, in the famous opening line of his 1953 novel, a moving exploration of a young boy’s loss of innocence, highlighted the problems inherent to memory and history. Reconstituting the past to chart collective and individual memory entails revisiting experiences and impressions that often seem distant, unreliable, lost. Transmuting fantasies and fears that lie in the realm of the past into stories is not without its own sets of challenges. While writing springs from memory, it is also likely that memory itself springs from writing.

Andreas Huyssen, Villard Professor of German and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, believes that the past is not simply there in memory .... it must be articulated to become memory.

Michael Ondaatje, in his seventh novel, Warlight (Jonathan Cape), his first in seven years, explores the commingling of memory and history, the various ways half-remembered past can shape our idea of ourselves and our understanding of the world, love, relationships and familial ties. Wars scar. Individual stories of people caught in the vortex of the war-time upheaval — espionage, secret missions and destruction of the evidences of savagery — become the repositories of the various ways wars take a toll on human lives, destinies: “The past never remains in the past. Wars don’t end. They never remain in the past.”

The novel, which pits the freedom of adolescence against the turmoil of post-war England, our love for certitude, and the certitude of love, against the uncertainty of life, unfolds like shards of splintered memory — luminous, shadowed — piecing together its disjointed fragments, illuminating its dark recesses. Divided into two parts, the novel, which treads Ondaatje’s trademark territory of lives getting steadily obliterated by wars, is an elegiac spy thriller set during the post-second world War London. Its chapters seem like spirals that reveal its inner, intricate structure slowly, like the petals of a flower before it blooms into being.

Its unattributed epigraph sets the tone: “Most of the great battles are fought in the creases of topographical maps.” The opening sentence sets everything up: “In 1945 our parents went away and left us in the care of two men who may have been criminals.” As a reader, you know that it’s going to be a saga of a broken family in the wake of the war, with a certain mystery at its heart.

In 1945, Nathaniel and Rachel, in their teens, are abandoned by their parents and left in the care of strangers —a household lodger nicknamed the Moth, their official guardian, whose house is frequented by other similar characters like the Pimlico Darter, an erstwhile boxer and dog-racing fixer, Olive Lawrence, a glamorous ethnographer, and chimerical Arthur McCash. The siblings have little clues about their parents’ lives: “They had rarely spoken to us about their lives. We were used to partial stories.”

Almost every character in the novel has a nickname. Nathaniel and Rachel too have their nicknames — Stitch and Wren — and their mother calls them by their nicknames. “Ours was a family with a habit for nicknames, which meant it was also a family of disguises.” Later, Rachel rebels against this and severs her ties with the family. She advises her brother: “Your name is Nathaniel, not Stitch. I’m not Wren. Wren and Stitch were abandoned. Choose your own life.”

In war-ravaged London “that still felt wounded and uncertain of itself” Nathaniel and Rachel are left to fend for themselves. They join the Darter as he cruises through London’s waterways at night, transporting greyhounds and other cargo wrapped in mystery. They are sent to boarding schools, but run away from them. As they learn to deal with the absence of their parents, being brought up amid strangers, they seek refuge in love, holiday jobs, forming their separate universe. Nathaniel, the narrator, recollects: “My sister and I were by now foraging for ourselves, becoming self-sufficient, Rachel disappearing into the evenings. She said nothing about where she went, just as I was silent about life on Agnes Street (it is here that Nathaniel finds his first love, Agnes). For both of us school now felt like an irrelevancy.”

Staring at uncertainty, Nathaniel muses: “When you are uncertain about which way to go as a youth, you end up sometimes not so much repressed, as might be expected, but illegal, you find yourself easily invisible, unrecognised in the world.” At some other point he says: “If you grow up with uncertainty you deal with people only on a daily basis, to be even safer on an hourly basis. You do not concern yourself with what you must or should remember about them. You are on your own.” Silence envelops everything: “Omissions and silences have surrounded our growing up.” Writing about this phase of his life, Nathaniel says, “I’m still uncertain whether the period that followed disfigured or energised my life. I was to lose the pattern and restraints of family habits during the time, and as a result, later on, there would be hesitancy in me, as if I had too exhausted my freedoms.”

As a boy in London, Nathaniel obsessively draws maps of his neighbourhood in order to feel secure. “I thought that what I could not see or record would cease to exist, just as it often felt I’d misplaced my mother and father in one of those small villages flung down randomly onto the ground with too similar a name and with no reliable mileage towards it.”

In the second part of the novel, the narrative shifts to 1959. Nathaniel, now 28, buys a house in Suffolk, where his mother Rose Williams, codenamed Viola, grew up. Working at the British Foreign Office, Nathaniel reviews secret service files and dossiers to solve the jigsaw of his mother’s involvement in clandestine operations during the war. Random events like a bombing in Jerusalem, a massacre in Yugoslavia, a secret operation in Italy are traced to her. We get to know, for example, that Marsh Felon, the thatcher’s son who fell off the roof of Rose’s childhood home in the first part of the novel never really left her life. Determined to know the story of his family’s dissolution, Nathaniel unearths buried clues after his mother’s death to find connections between mother’s disappearance and reappearance, the scars on her arm, and the roles of The Moth, The Darter and Olive Lawrence who populated their childhood. Towards the end, Nathaniel says, “I know how to fill in a story from a grain of sand or a fragment of discovered truth.”

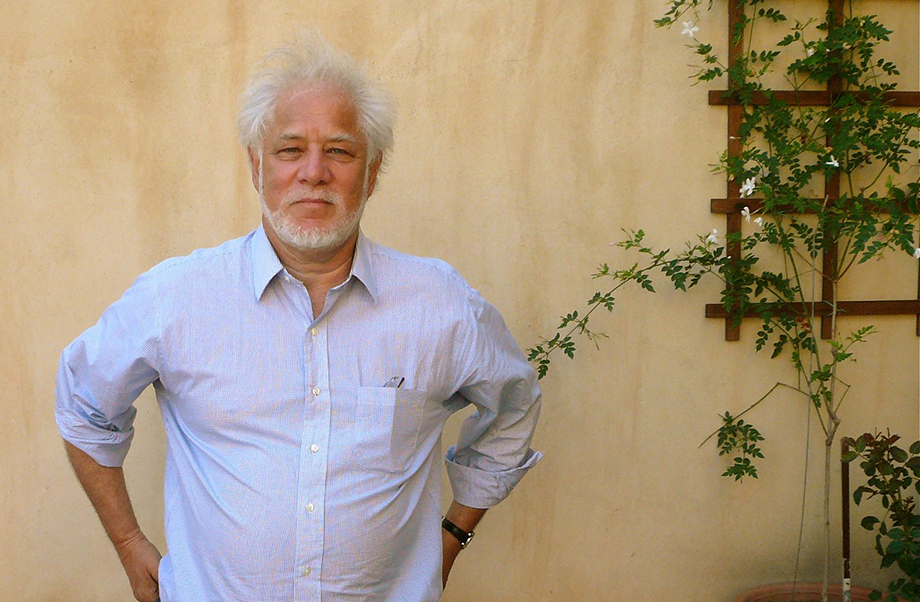

Ondaatje is interested in the archaeology and the archives of memory. Almost all of his novels begin with one image that stays with you. The rest of the story seems to be like a backstory. A great deal of what find their way to his novels, Ondaatje, 74, has lived and experienced. Born in Sri Lanka in 1943, Ondaatje grew up surrounded by his extended family on an estate in Kegalle owned by his paternal grandfather, a wealthy tea planter. In 1952, four years after his parents’ divorce, Ondaatje moved to England with his mother, sister and brother. Back home in Sri Lanka, Mervyn Ondaatje, his father, drank himself to death. In 1962, Ondaatje moved to Canada where he has lived ever since.

Ondaatje’s 1992 novel, The English Patient, which was a joint winner of the Man Booker Prize, recently won the Golden Man Booker Prize, declared the best work of fiction over the past 50 years. In his novels, Ondaatje draws on his own life to tell tales of duality, displacement, exile and loss. “Do we eventually become what we are originally meant to be?” Nathaniel wonders at some point in Warlight.

As a writer, Ondaatje seems to be interested in exploring an individual’s connections with the wider world. Those of us who have followed Ondaatje’s illustrious journey know the wonderful ways he blends prose with poetry. His novels stand out for being economical and lyrical. In his fiction, the boundaries between real and fictional lives blur. Life and art, biography and fiction all converge. In Warlight, a lot of what Nathaniel says at different points in the novel, seems to echo Ondaatje’s voice: “When you attempt a memoir, I am told, you need to be in an orphan state. So what is missing in you, and the things you have grown cautious and hesitant about, will come always casually towards you. ‘A memoir is the lost inheritance,’ you realize, so that during this time you must learn how and where to look. In the resulting self-portrait, everything will rhyme, because everything has been reflected. If a gesture was flung away in the past, you now see it in the possession of another. So I believed something in my mother must rhyme in me. She in her small hall of mirrors and I in mine.”

In Warlight, Ondaatje exhibits the adroit maneuverings of a master craftsman who maintains a total control over his narrative, ensuring everything fits in the larger pattern of the novel’s universe, with no strand left extraneous, nothing amiss. Reading Warlight is like walking through a blanket of fog and mist, with light surfacing at the end.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated