Roy's women, caught up in a 'critical juncture' of their lives, are all battling angst that can be traced back to the domestic space

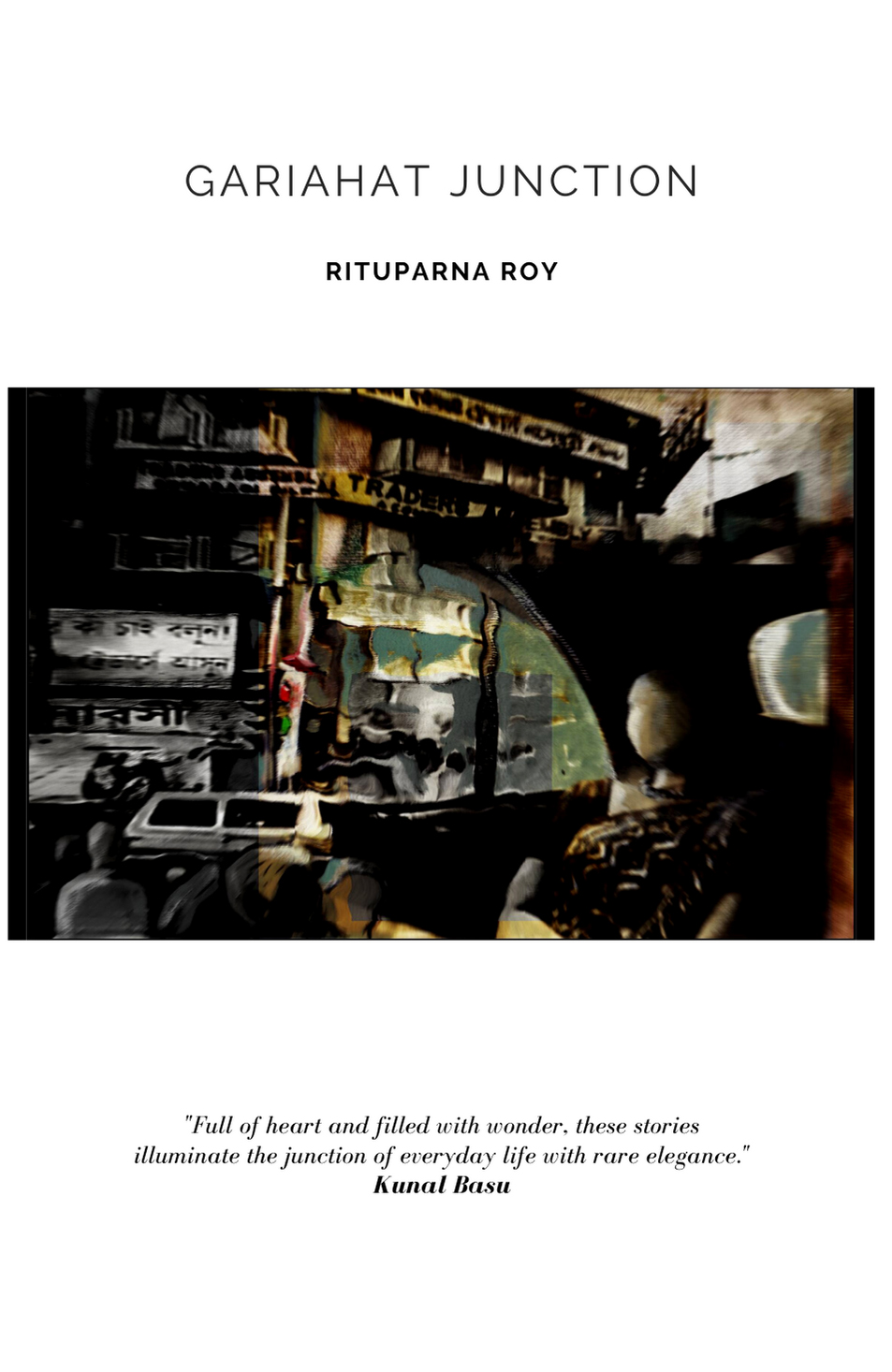

Occupying a large area in the heart of South Kolkata lies one of the busiest crossroads of the city. It is not only important for being the point where some of the major roads of Kolkata intersect, but also for being a prominent shopping destination. Numerous shops — ranging from big to street brands — flank the roads on all sides, adding a certain carnivalesque spirit to the place. Amidst the cacophony of the shopkeepers and the buyers’ over-heated bargaining debates, one can also spot hassled office-goers hunting for their next ride, excited youngsters making their way to some new eatery, sweaty pedestrians fighting the crowd to cross the street or eager first-timers wandering around in a half-dazed state. Here, buses zoom past with the conductor’s announcements ringing loud, taxis move haltingly in the hope of attracting passengers, and autos line up in a queue accompanied by an even longer human queue. And, right at the centre of this madness, a public chess club operates, where players calmly spend hours over a single move while the city chaotically speeds by. This utterly confusing, suffocatingly crowded, blindingly lit, deafeningly loud, amazingly well-stocked, but totally irreplaceable junction, known as Gariahat, is what gives name to Rituparna Roy’s debut collection of stories, published by Kitaab (January 2020) and nothing could have been more appropriate. The nine women — whose lives Roy freezes in the pages of her book — perfectly embody the junctural dilemmas that Gariahat Junction is capable of stirring up in the heart of even the most seasoned passerby.

Roy’s narrative flows in waves, trapping in its current women of all groups and ages. From the much-married to the just-married, the pre-adolescent to the spinster, the virgin girl to the pregnant mother, and the prude to the libertine, a rhythm is generated that seems strikingly similar to the crests and troughs of a periodic cycle that is all too familiar to all women around the globe. It is, therefore, significant that the book begins with the tale of a happily married woman at her sexual prime, pining for her husband sitting in a different part of the world for work and ends with the story of an “adult-child” woman pregnant with her second wishing that she could instead crawl back into her mother’s womb again. Somewhere, right in the middle of this curve, is closely fitted the stories of two women; one judged for not giving in to her sexual desires and the other for choosing not to surrender to the societal verdict issued in the interest of legitimising her desires. The two sides of this telling divide are occupied by women who seem boringly regular until one enters their cerebral space where intense battles are being waged behind the facade of submissive silences. These internal detours, so intimate — almost as if being trusted with one’s innermost emotions in all its rawness — would make anybody blush.

Escaping this internal space is not an easy task. Roy weaves a web of spaces, each trapped within the other. If at the centre of it lies the mind, the outermost circle is occupied by the home. It is strange how, even today, while telling the tales of women, one cannot but not situate it within the home turf. These women, caught up in a “critical juncture” of their lives, are all battling angst that can be traced back to the domestic space. No longer can we dismiss such spatial compulsions as a limitation of the woman writer — from Jane Austen to Virginia Woolf, everybody has had to face these criticisms. Rather, we must recognise the political imperative of such a choice. Roy beautifully demonstrates this through her characters. In “Imaginary Battles,” the unnamed protagonist loses sleep over a case of l’esprit de l’escalier and by the time we leave her she is sitting in front of her computer playing Solitaire, metaphorically arranging all the retorts she could have but did not hurl back to her father-in-law’s “provocative statement”. It is interesting how, throughout the story, she remains a “she” or a “bahu”, because isn’t that what her identity inevitably gets reduced to? But what is even more poignant is the way she chooses to battle out her inner ripples through a virtual game of cards — symbolic in its naming — as women do not get their vast fields of Troy.

Knowing this well, Roy makes sure never to speak for her women but let them do so themselves. In her careful narration, rich with immense detailing, she lovingly unravels each thought and explicitly spells out each action, using her words to show rather than tell. Her omniscient narrator (except for the “Dancing Queen” where Neelakshi chooses to tell her own story), does not exploit this omniscience save for giving us an uninterrupted live streaming of the character’s innermost spaces. Like, for instance, in “Madonna and Child,” when Bhavna is getting mansplained within the inner confines of her gynaecologist’s chamber how her desire for an abortion is actually her way of seeking attention, it is not her words that show her dissent but her silences. At the end of it, when they are returning back home, her husband Santosh puts his arms around her in their car. On any usual day, Bhavna would have pushed him away, conscious of the driver’s presence. Today, she merely looks far away from him, “lost in deep thought”.

Such powerful moments lie scattered across the length and breadth of the book. One highlight would be Kabita’s heart-wrenching question to her husband Binoy at the end of her tale: “Have you bothered to know anything about me? Ever?” The always quiet, never complaining, unassertive Kabita, who sacrificed her singlehood so that her brother could get married, sacrificed her research so that her husband could continue his, cannot remain silent anymore on finding that her entire PhD (of which only the typing was left) has been reduced to a pile of ashes by her “idealistic” partner, for his idealism was reserved for larger things and his wife was not part of that. Another such moment could be gleaned from the “Vanilla Sky” where little Paakhi experiences “the first pain of her clipped wings” when the Housing Committee of the complex that she stays in decides to dismantle the playground outside including the twin-swings. Paakhi does not say a single word — does she even have a say? Isn’t she just a child who knows nothing about how to protect herself from the big bad world outside? So she doesn’t. The story ends with her melancholically gazing at the pair of swings, in complete silence, and that is enough to make one’s heart ache.

In her “Acknowledgement,” Roy talks about growing up in a middle-class Bengali family in Kolkata where her mother instilled in her a love for literature. She would have known her Tagore well, he who has immortalised the definition of short story in the much-quoted couplet “Seshhoyeohoilonasesh” (a thirst for more even after the end). Most of Roy’s stories bear the stamp of this un-endedness, making the readers eager to know ‘what next?’ It is almost a crime to have turned the signal green in “Gariahat Junction” just as Katha was about to give the answer to a question for which she had left the readers hanging throughout the entire story. There is one more thing that leaves you frustrated — albeit in a way that bibliophiles love. According to Roy herself, these stories have been inspired by the lives of real women she has known and loved. Does that also mean that their lives would have intersected somewhere? That they would all be inter-connected in some way or the other? Could it be that the impassioned mail that Neelakshi writes to “[email protected]” about singlehood being her ownhappy choice is in fact Binoy’s Kabita? Who knows?

Comments

*Comments will be moderated