‘I write poems to document the hauntings of my memory'

A general propensity to question has continuously made me rethink what it truly means to be writing poetry. Born and raised in Kanpur, I learned one of the foremost lessons was stitching my tongue. Poetry came to me as the unbridling of my tongue from the strains of patriarchy. What aided my craft unknowingly was my grandmother’s retellings in the form of bhajans, religious hymns, and couplets, which became the first sounds that remained with me. She introduced me to what I now understand as Bhakti Poetry — writing love poems to the divine. This formative definition that drove me to pick the pen has become more complex over the years, but the essence remains unchanged. I write poems to love and document the hauntings of my memory.

I moved to America in 2018 to pursue an M.F.A in creative writing, which furthered my understanding on a craft level — specifically in terms of formal Western poetics. I acquired the language to encapsulate my gendered experiences into forms that aided my voice. My work has grown by reading my foremothers such as Maya Angelou, Sylvia Plath, Eunice de Souza, Adrienne Rich, Ismat Chughtai, Agha Shahid Ali, and contemporary poets such as Safia Elhillo, Tishani Doshi, and others. The distance from my home and land has also helped me gain perspective on what becomes “othered” via the centralization of Western poetry. This has stimulated me to return to the forms I grew up with, such as ghazals, dohas, and odes.

For the past two years, I have been working on my poetry collection titled The Mother Wound, which explores the inheritance of grief, loneliness, and trauma from my mother. Poems published in the magazine are a part of this work. Working on this manuscript, I have realized that the collective understanding of being a woman is tethered to instances of both violence and tenderness. The commonality of this experience is what binds women across the globe. My poems often deal with issues of domestic violence, abuse, and distortion of the female body. At the same time, I am wary of publishing anything that adds to the misconceptions about subaltern women. I am at a time in my writing journey where I am straddling the overlaps between personal and political through my work.

I like to think of my practice as worship. My writing has remained personal, but as my understanding of my privilege has become layered, my craft and voice have deepened to reach a space of looking inwards. Reflecting on the malleability of art forms and the intersection of ideas has, in turn, led me to pay attention to musicality in my work. I often return to my training as a Bharatanatyam dancer — my foremost education in encapsulating emotions — a skill that I continue to develop through poetry.

As I continue to learn, build, break and rebuild my work and voice through self-revision, I have realized the strength of a community-orientated practice and aim to make my writing more accessible. I believe in the transformative power of literature and writing groups; they are safe spaces for feeling seen and, ultimately, loved — something my younger self needed. So I hope to continue to heal and reclaim through the fluid grace of poetry, and the capacity it holds to both instruct and delight.

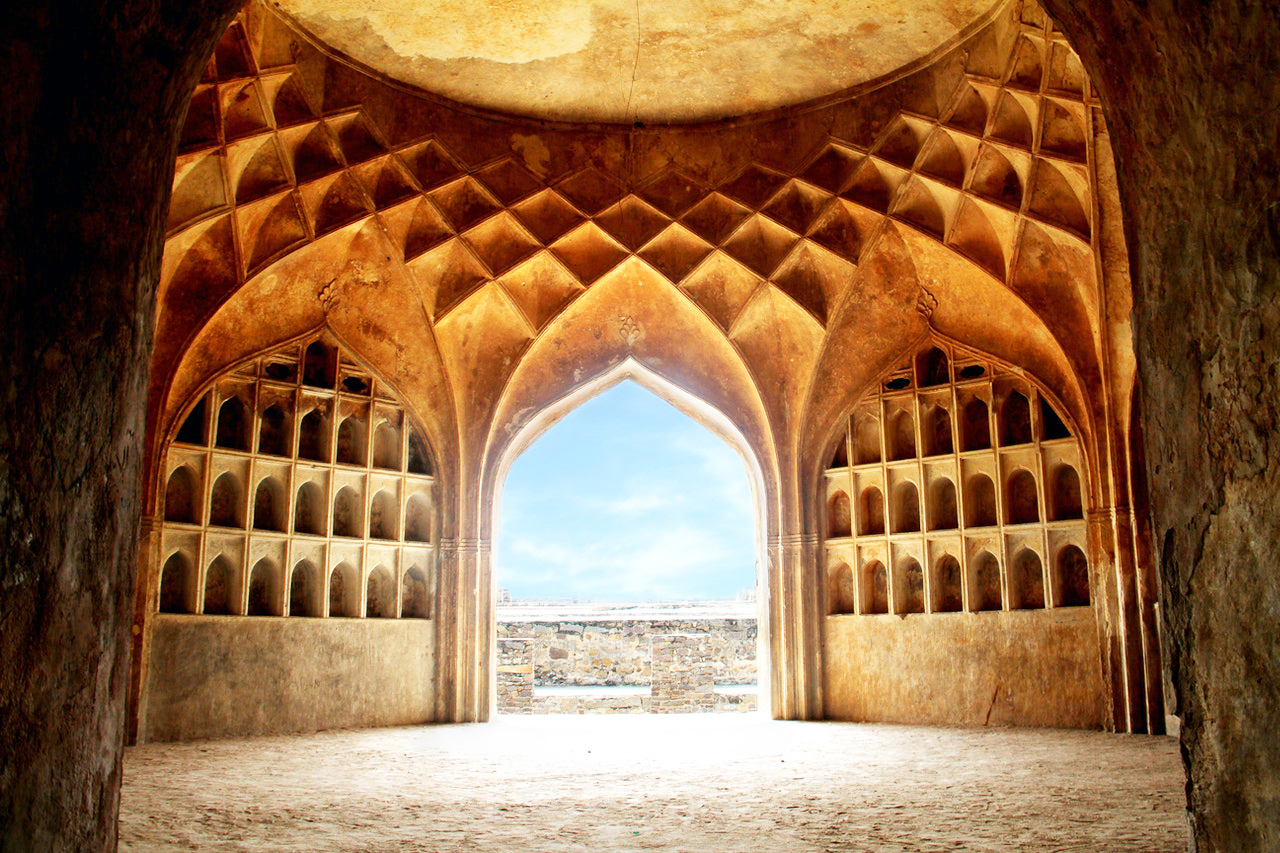

Ghazal After Babri Masjid

What gets into us when we tear down stone walls with stones

chanting for the want of a mandir.

Our gods sleep peacefully in blood-washed blankets

erasing the remains of a masjid.

Do we not know what happens when we burn a leaf in the forest?

a funeral pyre is lit inside every mandir.

We pray in languages we don’t love in, shouting incantations

digging deep for a masjid.

How many incense sticks burn to cleanse us of ourselves?

every firecracker in the sky blazes a mandir.

The flowers etched on the pillars and domes shrivel,

beneath each was planted another masjid.

I am the Qafia today and tomorrow the Kafir,

who will you call to worship your empty walls we killed us all, for a mandir.

Sister Sonnet

on Sharad Purnima

Nectar falls from the moon tonight.

We stand under the pink bougainvilleas

draping every cross-stitch of the cage, where our dog lived

and died. Quiet, so our thin limbs don’t convulse

the many faces of the moon god. We are in the verandah,

to collect droplets of the divine liquid

freeze it and wreathe a pearl necklace.

We smile knowing this will be a gift for Ma,

who makes us believe: Amrit rains from the sky tonight.

Waiting, we buzz like flimsy moths, under the silver light

stretching our arms towards the grey sky to catch just a few drops.

Some maidens swallow these tiny tears tonight

for good grooms, with clasped hands as each globule gathers

on the tip of their ripe tongues. The first drop plunges

and corrodes our skin. This is how we learned to drink mercury.

Prayer From A Non-believer

after Kabir Das

I turn to Kabir again, dear God.

Let me be a kafir. In all my ways.

Let me undo, dear mother who will not grow out of me.

A friend says they will marry the Muslim they love

after their parents die.

Amma asks, if you love someone

Won’t you set them free?

Is loving someone not enough

to set them free? I ask.

Who will be set free?

It’s my fault I think of poems as prayers.

The boy I love says Kabir was separated from Islam

so his songs could be tuned to our burning incense sticks.

My mind blooms with my favorite story.

Where Kabir the poet, kafir and saint, dies.

What he didn’t get in life, he finds in death.

A mystic, weaving garlands is avowed by both, us and them

as a child of our god. On the banks of the holy river,

they quarrel about his body.

Bury or burn. Burn or bury.

Swearing to fight death with blood.

But when the sun spills the sky orange

his body dries to flowers.

A shroud of bougainvilleas.

They pouch them in equal halves. Burn some, bury some.

The boy I want to love tells me if I marry him I will not be buried. He will not be burnt.

The question I remain with is why can’t our bodies turn to flowers too?

He smells like a rush of night jasmines.

Numismatics For Mothers

Ma’s collection is piled

in a pink pouch embroidered with gold spades

tucked in her cupboard

my milk teeth rattle with glee

searching for orange melts

as I chance upon this treasure

the tinkling of a thousand coins

tricks me for temple bells

every time I reach my hand

in the back of the cupboard

the stack grows taller

now I hunt for jewelry

and feel the metallic chinking

of the emblems embossed on the coins

until I find one in auntie’s cupboard

and then in ama’s and then in dadi’s

Ma explains all women

in our family collect coins secretly

lest we need to leave

we never leave

the piles only grow bigger

change remains unexhausted

in our termite-eaten cupboards

Elegy For Our Garden

first the roses

shriveled in my palms

it was not the thorns

that milked my heart of blood

but knowing me knowing you

this week I killed

the last plant

in our glass house

a money plant creeper

that you insisted

is the devil’s vine

mine to carry

in not watering it

I was saving the spider

spinning a silken home

silvering the dark brown

roots of the ivy

I hoped the spider would find

another house to hold

but every week the black widow

became more familiar

and the webbing blinding

when the ivy browned

all the way up to the balcony

where butterflies flapped

and you once read Marquez

I poured and poured and poured

too late to save anything

The essay and the poems are part of our Poetry Special Issue (January 2022), curated by Shireen Quadri. © The Punch Magazine. No part of this essay or the poems exclusively featured here should be reproduced anywhere without the prior permission of The Punch Magazine.

Comments

*Comments will be moderated