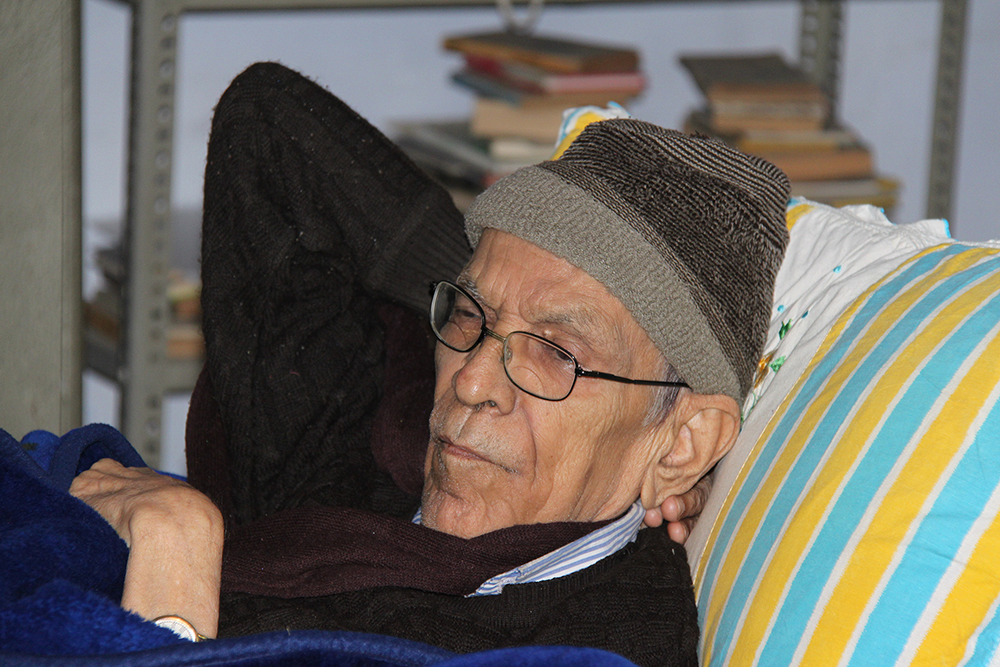

Naiyer Masud. Photos courtesy of Mehr Afshan Farooqi

Mehr Afshan Farooqi, daughter of Urdu doyen Shamsur Rahman Faruqi and a professor at the University of Virginia, on her memories associated with Naiyer Masud

Whenever I look at sunflowers I think of Naiyer Masud. My father addressed him as Mir Sahib; for me he was Naiyer chacha. A tall, angular man with a gravelly voice that was strangely mesmerizing. I heard him before I met him. One afternoon as I crossed the front verandah of our rented house in Lucknow, an unfamiliar voice floated from the living room. Someone was singing a ghazal I recognized as my father’s:

Ghar ghar khile hain naz se surajmukhi ke phul

Suraj ko phir bhi mana-e didar kaun hai.

At every door, sunflowers bloom; prideful-coquettish

What is it then that bars the sun from looking?

Curious to see who the singer was, I peeked through the partially closed door. Sitting across from my father’s desk was a man singing in a low, oddly soothing voice. He had a long neck with a prominent Adam’s apple that agitated as he sang. An elongated, almost horsy face as arresting and distinctive as his voice. My father called me inside when he noticed me standing by the door. I was tongue-tied as I was introduced to Naiyer Masud and then fled from the room as soon as I could.

My father was posted in Lucknow through the 1970’s. Those Lucknow years were special and impressionable for me, a twelve-year-old, awkward and consumed with shyness. Lucknow’s milieu was quite different from Allahabad. The city managed to carry its colonial legacy, nawabi grace and headiness of democratic freedom all at once. It was modern, it was medieval, it had a special space for Urdu literary culture, a lingering Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb if you will. We lived in a house in River Bank Colony not far from the Gomti river. (I should clarify that the River Bank Colony house was more like a summer residence for me. My mother, a dedicated educationist, was the principal of a girl’s school in Allahabad. My sister and I continued our studies in Allahabad). It was a pleasant neighborhood. One could easily walk to the park gardens around the ruins of the British Resident’s house and explore its crumbling rooms. Evening walks by the Gomti river to the Shahid Smarak (memorial for martyrs) and watching the twinkling lights on the river are etched in my memory. Naiyer chacha’s family residence was in the heart of the old city, in a neighborhood known as Nakhkhas. It was a grand bungalow, aptly named Adabistan (abode of literature) built by his father, Masud Hasan Rizvi Adib, the renowned scholar of Urdu and Persian. Naiyer Masud’s parents and siblings lived in the spacious bungalow.

Naiyer Masud’s family residence was in the heart of the old city, in a neighborhood known as Nakhkhas. It was a grand bungalow, aptly named Adabistan (abode of literature) built by his father, Masud Hasan Rizvi Adib, the renowned scholar of Urdu and Persian. Naiyer Masud’s parents and siblings lived in the spacious bungalow.

Adabistan fascinated me. The house was midway between a bungalow and a traditional Muslim residence. It had distinct spaces for women and children. There was a side entrance through a high, heavy wooden door usually left ajar. The front entrance was essentially for male visitors. The wooden door led into a lobby of sorts which opened into a vast courtyard. One side was flanked with an assortment of rooms; but the main building was way across at the opposite end. An ample verandah furnished with takhts was the main living and dining area. There was an imambarah (inner sanctum) nestled behind it and a warren of rooms leading off from it on one side.

Naiyer chacha’s mode of transport was a motorized bicycle marketed as the “Vicki.” Sometimes he visited us with a friend, Dr. Kishore, who was big and jovial and a poet. He too rode a Vicki that sagged dangerously under his weight. They seemed a strange pair; the rotund, jolly poet and the lanky, scholarly Naiyer Masud. I can still visualize the Vicki, leaning against the wall of the narrow passage that led to our house. It alerted me that Naiyer chacha was visiting. Conversation floated from the living room through the summer evenings, culminating in dinner. Then, there were evenings spent in Adabistan ending with dinner.

The drive to Nakhkhas was through a sea of traffic. On both sides, the street was flanked with shops and road-side hawkers. The weekly market at the Nakhkhas was specially exciting because there were vendors selling birds and other small animals that could be kept as pets. Soon we had a large cage of chirping little finches with red beaks and flecks of red plumage called lalmuniya. A mountain mynah, orange beaked, sleek, ebony plumage with a startlingly yellow crest on her head joined the menagerie. She was named Shirin (sweet). Pigeons joined the growing bird population. A baby peacock chick named Mirzaji was allowed to roam the house. My memories of Naiyer Masud, the River Bank house and the birds all go together. He would announce himself by calling “Faruqi sahib” in his deep voice from the front verandah, and the birds would send off a musical response. Our cook would rush to the door and Naiyer chacha would step inside. I noticed that he preferred to carry his stuff in a large-sized pocketbook tucked under his arm. When tea was brought in and my father lit his pipe, Naiyer chacha might extract some papers from the pocketbook, or my father would bring something out, discussions would flow right up to dinner time.

Poetry flowed, stories grew and flowered, adabi mahfils scented with tobacco smoke filled the air. Naiyer chacha smoked an unfiltered brand, Charminar. Then the river overflowed; there was a flood. The Gomti river was in a spate. It inundated half the city. River Bank Colony was submerged. My father moved to stay with Naiyer Masud in Adabistan. In Allahabad, we anxiously watched the news. When the waters receded, it took a month before the house was habitable. Lucknow in the 1970s was susceptible to outbreaks of “rioting”. They were sudden and violent. Clashes between Shias and Sunnis. Whenever this happened, the old parts of the city were cut off from the rest and put under curfew. There was a time when Naiyer chacha was at River Bank Colony and curfew was imposed in the old city.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

A delightful piece on Naiyer Masud, who perhaps was one of the last in the realm of Lucknow culture. But he has left behind a substantial heritage in the shape of his stories in Urdu which will sustain him as a great writer of a style and genre which cannot be easily defined. But they are stories which need to be read and read again few times to fathom out the true meaning behind those tales.

Surjit Kohli

Aug 22, 2017 at 15:24