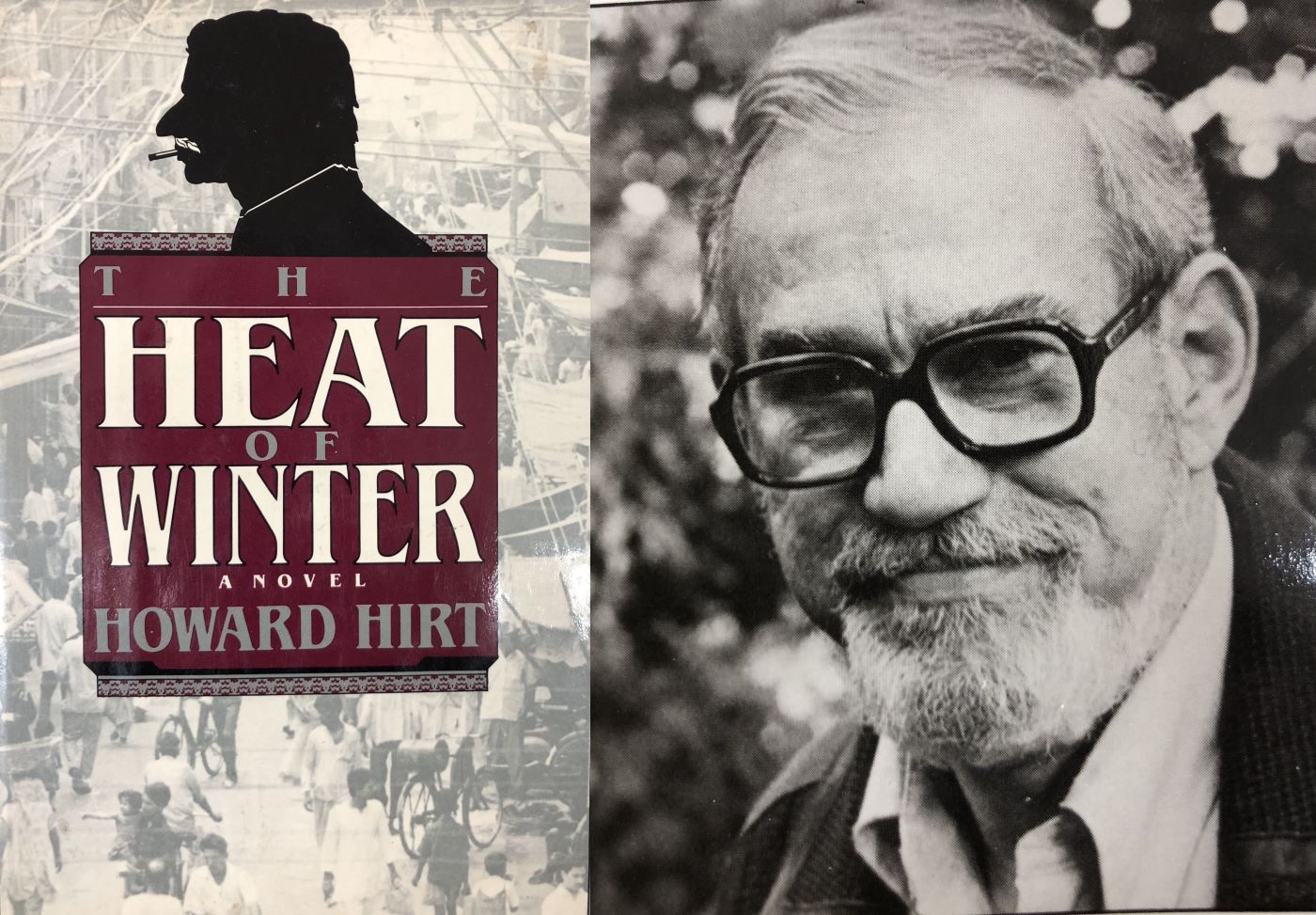

Photos courtesy of the author

The Heat of Winter by Howard Hirt is an intriguing novel set in Aligarh, India, in 1952, featuring a plot inspired by Frederick Forsyth’s The Day of the Jackal. The story weaves through Hindu-Muslim tensions, political power struggles, and a love affair against the backdrop of a fictional visit by former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru; it offers detailed insights into the social dynamics of the city and university during a tense period post-Partition.

Few would have heard of an obscure novel, The Heat of Winter, written by an equally obscure American author, Howard Hirt. I stumbled upon it in my old books during the lockdown. It intrigued me because it described a plot woven around a fictional visit of the first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru to Aligarh and a thwarted assassination attempt on him. The year is 1952 — just four years after the Partition — a period when the atmosphere in the country is tense, with communal riots happening in many parts of North India. A certain city in Uttar Pradesh, about a hundred miles from capital Delhi, which is famous for its Muslim university (no marks for guessing that it is Aligarh Muslim University/AMU) and also as a town well known for manufacturing locks, has seen the worst communal riots in which Hindus and Muslims have cut each other’s throats. On a certain day in February, Nehru, a great supporter of the secularist cause and granting protection to India’s Muslims, is on his way to Aligarh (‘Ramgarh’ in the novel) on the Grand Trunk Road. Here, he will address the students and faculty in a function to mark the appointment of the university’s new vice-chancellor. And it is here, in the public function, that Nehru’s assassin is waiting.

It does not take a detective to discover, just after reading the first few chapters, that the plot of the novel is inspired from Frederick Forsyth’s 1971 novel, The Day of the Jackal, which was made into an even more famous movie in 1973, starring Edward Fox and Michael Lonsdale. Its story revolved around a plot by right-wing nationalists in France to kill President Charles De Gaulle in 1962. In The Heat of Winter, for almost a month before Nehru’s arrival in Ramgarh, a plan is hatched by some right-wing organisations in the city to assassinate Nehru and pin the blame on Muslims, who are agitated by the growing majoritarianism in the country and the hate propaganda of these organizations. And Mohammed Abdul Karim, the equivalent of Deputy Commissioner Claude Lebel in The Day of the Jackal, is the city’s newly appointed superintendent of police whose job it is to ensure Nehru’s safety. Much of the story revolves around his attempts to uncover the conspirators and prevent them from having a shot at Nehru. And there are times when he narrowly escapes attempts on his life, including a bomb explosion in a train.

As those familiar with the city would know, essentially, there are two Aligarhs — one is the Aligarh city, the shehr; while the other ‘Aligarh’ is the campus and the residential areas surrounding AMU, the university which arose from the Mohammedan Anglo Oriental (MAO) College, created by the great 19th century educationist and social reformer, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan. Like the Gaul’s village in Asterix comics, this is a unique world, with its own distinctive characters and stories. These two Aligarhs are not only separate in the popular imagination but also exist as discrete entities, only estranged from one another by the Delhi-Kolkata railway line, joined only at some points, by overhead bridges and level crossings. The Civil Lines, lying across the railway line, were developed by the British and even today, with their straight wide roads and planned development, they present a picture of order. It is here that the university is located. A map in Hirt’s novel shows the difference between the two Aligarhs clearly. While the AMU is depicted to be the world of Urdu-speaking, genteel folk, Aligarh city or shehr, which lies across the Delhi-Kolkata railway line, is referred to as an area of filth, vice, and crime with its brothels and akhadas — where wrestlers compete against each in mud pits.

Hirt’s story is riveting as the plot moves through Hindu-Muslim tensions in the city, the sleazy world of brothels, lock-making units in the city and the local politicians jockeying for power. This world of the Ramgarh (Aligarh) shehr is contrasted with the genteel, Urdu-speaking world of the university teachers, displaying social etiquettes of cultured north Indian Muslims. In this, Hirt inserts a love story, too: the affair blooms between Ellen Siddiqi, the American wife of a chemistry professor in the university, and Abdul Karim, the hero of the novel. The university campus is beautifully described; anyone who has visited Aligarh will testify, its buildings, including the residential quarters for university professors, are a treat for the eyes.

As a person familiar with Aligarh, what interested me about the novel was the details furnished about the town and university. Not much is known about the author, Howard Hirt, except that he was a professor of Geography at Framingham State College, Massachusetts, USA and visited India as a Fulbright fellow, possibly in the 1950s or early 1960s. However, from reading the novel, it does seem that he did his homework extremely diligently and seems well informed about the social milieu of the university campus, the goings-on in the city, the polarized atmosphere in post-independent India, and the role of right-wing groups in anti-social activities, and several other details. The texture of his narrative is crowded with minute physical or historical details which though for an Indian reader may seem overstating the obvious, but for his first world readership were required. So, gulab jamuns are “oval balls of fried milk solids swimming in syrup” and halva “a sweet mound of carroty confection covered with a sheet of finely beaten silver foil”. Ganesh is “the elephant God of Wisdom and Success, the Remover of Obstacles” and Indian women are seen on tennis courts clad in “shalwar pants’ and “kameez tunics”. I was struck by the “Jai Hind” on the dedication page.

Several characters mentioned in the novel, especially those from the university campus, could be easily named and traced back to real life characters, as those familiar with the AMU of the 1950s and 60s (including this author) would know. One has to remember that the period of Hirt’s stay in Aligarh (not known but likely to be sometime in 1960s) was a period when Dr. Zakir Hussain as the vice-chancellor of AMU (1948-1956) had left behind a legacy of progressive atmosphere on the campus. This was a period when the campus cultural activities were vibrant. Since many of the faculty of AMU had left for Pakistan post 1947, Dr. Zakir Hussain as the vice-chancellor invited several famous scholars (Prof D P Mukherjee in Economics, Prof Munibur Rehman in Islamic Studies, Prof Ghanysham Singh and Prof Bose English, and many more) to join the university. The university had a few well-known scholars already among those who had not left for Pakistan. Prof Mohammad Irfan Habib of History, to name one, who makes an appearance in the novel, albeit under a different name. The wife of a famous professor who used to play tennis in the staff club, a certain Mrs Abida Shamir, also is most probably a real person. Mrs Shamir regularly joins Ellen in tennis matches at the staff club (It is left for the reader to guess who Mrs Shamir is).

All in all, The Heat of Winter makes an interesting read. It would be, as a blurb on the jacket says, “A sort of Indian Day of the Jackal — big, brown beads of fact strung on a fine-spun thread of story; the interesting, intimate facts of Indian existence as seen if not by a Kipling perhaps by another John Masters”. Perhaps someday someone will get the idea to make it into a film.

Comments

*Comments will be moderated