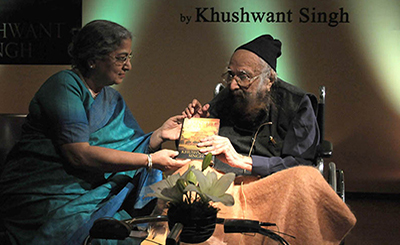

Nimmy Raphel, actor, dancer, musician, and puppeteer at Adishakti. Photos courtesy of Nimmy

As an artist, I liked the evening better. The slow transition that one goes through from light to darkness; for me, this was where I felt Time because it was in front of me — colours changing, people changing, people gathering, the smell of tea; to me, it felt like everyone was in anticipation of something that’s not tangible.

Where did it all begin? Frankly, I don’t remember. Did I always want to be an artiste or is it something that I aspired towards, later in life? Growing up in a village, without electricity, the evenings were the most exciting. The ritual of cleaning the oil lamps, the soot painting your fingers to match the darkness outside. The smell of the kerosene and finally when the lamps are lit, you will only see what the lamps allow you to see. Those hours in the evening we bathed ourselves with the tinge of amber from the oil lamps and the stories would begin, mostly they involved ghosts. I guess I was fascinated by the theatricality of it all from the very start. That was my stage.

Growing up in a house full of people, I don’t remember ever studying. The days were spent with one game leading to another. Making up stories of movies for which you have only seen the posters, becoming the characters that only existed in your mind, though it all I recognised one fundamental thing about myself, I was a storyteller and I believed in stories passionately. I remember fooling my mother into believing I was the rank holder in my class. And reenacting the scene again to her I started believing in it, too — the outcome of all that was that it gave me an excuse to stay away from text books and to climb trees. Sitting up there, watching the world go by, this habit of climbing tress earned me my nick name “Maramkeri Mariyamma” (Mariyamma who climbs trees).

From this very unstructured life, where boundaries only existed where you decide to keep them, I went to Kerala Kalamandalam, a school for traditional arts.

Six years of intense training in dance were difficult. I kept wondering, why we had to wear six different coloured blouses for each day of the week, It felt like the discipline was also ingrained into those coloured blouses we wore but through it all what sustained me was the friendships that we built. Even to a point of knowing each other’s strengths and vulnerabilities on stage and to accommodate that without losing a beat needed skill.

Transitions are a key aspect of an artist’s life. In my case, it was meeting Veenapani Chawla and Vinay Kumar of Adishakti, a laboratory for theatre, situated on the outskirts of Auroville. I am of the belief that every artist should be blessed to have mentors, who anticipate your growth as a performer even before you do, for me they were that. I admired them so much that my goal was to become them. Knowing them, I realised what it takes to become an artist — it was patience. How to slow down time against the fast moving world outside and to repeat your craft as an actor tirelessly, every day, and the most crucial, the confidence that one has to acquire to fail.

Being in Adishakti, in the environment of exploration of one’s craft I was reminded of something, that strange familiarity which never left me as I entered the campus, and that was the rediscovery of the playfulness of my childhood with the discipline that was ingrained in me from Kalamandalam, and both this combinations, is what defines me as an artist, even today.

As an artist, I liked the evening better. The slow transition that one goes through from light to darkness; for me, this was where I felt Time because it was in front of me — colours changing, people changing, people gathering, the smell of tea; to me, it felt like everyone was in anticipation of something that’s not tangible. And, in these evenings, when I heard VP and VK talking to each other, it was the best performance I could watch. The confidence they had in each other’s views and mostly not hesitating to challenge it, respectfully, witnessing those conversations, even though I completely failed to grasp what they were discussing because I knew very little English back then but that laid a foundation for my thinking as an artist.

In my artistic processes, I was encouraged to become conscious as an actor. It involved the observation of myself with detachment — every day, at every moment. Such a process is very difficult to execute on a daily basis. The only encouragement I had was that it would result in enhancing my peripheries of artistic growth. These exercises resulted in two things — one, to observe the complexity of human nature and to extract that information for performance and research. The second was that the realism and the psychology that you witness are only a fraction of one’s personality.

One of the crucial turning points was learning to write and direct myself. I knew I had to be responsible for owning up to my views in whatever medium I choose to express in. When the work began, what scared me the most were the silences that I encountered. For days, nothing would manifest. I would sometimes end up just walking about on the stage or just sleeping. Given the fact that my characters were Kumbakarna and Laxmana, it fitted perfectly. Most of the time, it felt like I was looking at another my-self but this other self was the characters that i was exploring. We continued to stand and stare at each other for quite some time, silence blanketing us, and then there was a break, like how I lit my oil lamps, I saw my characters in front, not a clear vision but enough for me to make sense of and to bring them to life through repetition. Making Nidravathwam taught me two things — one that creativity is a hard-earned everyday process and two, that I have to be responsible for the vision of the director who trusts me as an actor. Because for an actor, God is in the details.

In many ways, Veenapani and VK are my enablers. They are constantly challenging me to move outside the known frames of knowledge, nudging me to see the possibilities of what lies outside one’s comfort zone, to see what exists outside the known systems.

I am always reminded of a poem from one of Veenapani’s production called “The Hare and The Tortoise”.

There was a knowledge seeker

Hedged in by human limits

He sacrificed the main road

To take a zig-zag bylane

Though he lost much time

He grew a wiser man.

This piece is part of The Women’s Issue, curated by Shireen Quadri

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

.jpg)