It was not until the age of fifty-four that I had my first brush with a serious health concern. Until then, my overall health could have been summed up in one word: robust. But along with that, there were certain inborn “propensities” that required close attention.

My teeth had not been acquired from the best gene pool which therefore required timely visits to the dentist. At the best of times, an unwelcome tryst!

In my late twenties, my eyes had to be tested and I was put on a routine of eye drops because of a family history of glaucoma.

Headaches became a close companion during my teen years but in retrospect, I realised, that they were symptoms of adolescent conflicts and confusion.

In what ways was I strong and energetic?

While I was not the athletic type — I preferred to draw and paint and was a voracious reader — certainly I was the outdoor type. I loved long walks, swimming, gully cricket (lots of it), cycling, kite flying, tree climbing, marbles, badminton, carrom, cards, and other Indian games. Whenever I had access to a table, I realized how much fun table tennis was. It also led to a painful and scary experience.

I was in my mid-thirties and teaching at Sophia College in Bombay. During office hours, I played vigorous table tennis, sweated, and overlooked drinking enough water. I was home when the dehydration began to have its effect. I was writhing in pain, twisting and turning on the floor. I thought I was going to die. Over the next few days, a steady intake of fluids and homeopathic medicine, resolved the kidney infection. I never made the same mistake again and there was never a recurrence of that infection.

I also seemed to have good immunity against everyday ailments which occur seasonally or from endemic causes — things like cough and cold, fever, flu, migraine, digestive upsets. In later years, I was susceptible to acid reflux and to constipation. The only time I took leave of absence from work was when I had lower back muscle cramps which virtually laid me flat.

Then, on January 2, 1999, came the big one which blew the robust condition to pieces.

*

In the midst of a snow-storm in the American Midwest, I was shoveling snow from my driveway which was several inches thick and still falling. After a few minutes, I came inside to rest, then, went out again. The second time I needed a break, I lay down on the bed out of breath with a feeling of tightness in my chest. My wife, who is a nurse and who was luckily home that day, took one look at me (she later described my face as looking “ashen”) and called the doctor who advised her to take me to the ER right away. After we got into the van, it could not cross over the mound of snow where the driveway met the street. I asked my wife to exchange seats, took the wheel and drove the two miles to the hospital. As soon as we reached the ER, the staff hooked me up to the heart monitor. I was having a heart attack! And I had driven myself through slippery road conditions to the hospital without a mishap.

The ER staff stabilized me, but my wife had saved my life by reading the signs accurately and moving swiftly into action. The angiogram found five occluded arteries — three of them serious enough and two over 90% blocked. I would need a 5-vessel bypass operation. I thought to myself: this is it; I am not getting out of this alive.

I promised to mend my ways, change my diet, do anything to avoid a surgical solution but the family physician and the resident doctor were insistent. I had no other choice. Truth be told, I was terrified of the idea of open heart surgery. Later that day, the Dean of the college faculty made a bedside visit and told me: Listen to the doctor. The day after, I was transported by ambulance to a bigger hospital where the operation was performed without any complications. It was the longest seven hours for my wife who waited alone in the visitor lounge. We had no family to call upon for support. That I am writing this account 20 years later, is a testament to the expertise of Dr Bobby Kong. Most surgeons stick to and excel in a single specialty. They practise what looks like conveyor-belt operations from morning to evening. This can be seen as advantageous because they hone their skills every day and could do the procedure with their eyes closed, so to speak.

I was released after two days with follow-up instructions on cardiac rehab and agreeing to meet with a nutritionist.

While I had lived an active life before the attack, walking was the only exercise I got. I hated the idea of a regular routine at the gym. But as soon as I was back to work, I joined the local YMCA and did a cardiac workout 3-4 times a week. I have maintained this for 20 years and since retiring, I go seven days a week most of the time. It is very encouraging to hear my doctors say that I am the ideal heart patient. Six-monthly check-ups became yearly with a stress test every two years.

The new regimen focused on eating right at a fixed time and regular exercise. Ten years of indulgence in ice-cream, pies, half & half, cheese, and no exercise had taken its toll in clogging my arteries. Besides, studies showed that South Asian men whose lumen of the artery was narrower than those of Caucasian men, were genetically more prone to suffer the ill-effects of dietary misbehavior.

Of course it wasn’t a smooth ride all the way. Apprehensive moments were triggered along the way by tensions, disturbances, both personal and professional. Watching the war erupt in Iraq gave me palpitations. On a trip to Purdue, I felt chest pains while having dinner in a restaurant and paid the mandatory visit to the ER where after the four hour cardiac drill, it was declared a false alarm. Anxiety would shadow me from then on.

Raising two girls in the toxic American culture only compounded that anxiety. And Xanax calmed me down, helped me sleep. Dependence on pills was never a treatment option for me. Having been raised on homeopathy, I was averse to allopathic medicine and its well-recognized side effects. But, over the years, I have joined the tribe of pill-takers. And, I have to admit, I am alive today because of modern medicine and advances in surgery.

What did this life-changing event teach me? Foremost — Listen to the wife; trust her instincts and her training. She worked in the pediatric and thoracic unit as well as adult cardiac care and dealt with these patients on a daily basis. Two: We all know that life is short. It is not for throwing away; only a crisis brings home the value of preserving it. Three: Bad eating habits can be overcome; wholesome ones can be cultivated.

What did the gift of twenty additional years do for me? The obvious lesson was one about the fragility and unpredictability of existence, of not being lost to my family, to seeing more of the beauty (and ugliness) of life, to valuing friendships, to learning more about the mysteries of life and the changes and challenges it offers on a daily basis; to enjoy the small pleasures of life — food, music, reading, movies, scintillating conversation, giving and receiving kindness.

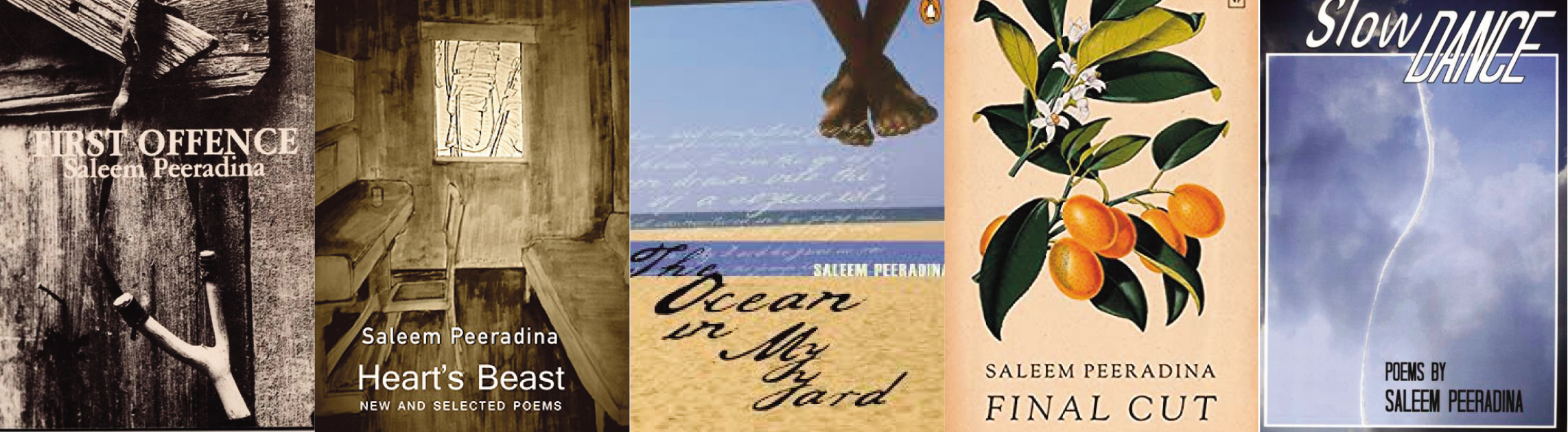

Professionally speaking — publishing a memoir, three additional books of poetry to my existing three; a collection of Selected Poems and another of non-fiction in the works. I had promised myself five books over my career. I got more than I wished. I have reason to be content.

The most important gift which very few people are granted is a change in perception — literally, a lifting of the fog through which you have been perceiving the loved ones in your world. Just as adversity and deprivation, injury of a disabling kind forces you to question and re-examine your presumptions in ways you had never anticipated, the heart attack had set off an alarm whose bidding I had to obey. I had been an introspective, self-absorbed creature which I had always justified as necessary for my poetic and artistic pursuits. Now I stood in the glaring light of my own insensitivity toward the tenderness, the devotion, and support my family had provided in ample measure. Not only in the past, my parents, but now in the present, Mumtaz, who has been and continues to be my strength and support to make everything possible for me.

I must note here that my wife has had her own encounter with severe knee pain after multiple knee surgeries couldn’t fix the first knee-replacement operation which was botched by a surgeon of repute. This surgeon belonged to that band of physicians who do not take women’s health complaints seriously and think that it is all in their heads.

*

Diabetes usually appears alongside or follows heart problems. The likelihood increases significantly where there is a family history. Glucose tests confirmed that I did have Type 2 diabetes.

Of course, treatments for keeping glucose levels at an acceptable level ranging from diet to pills to insulin are common knowledge. These practices enable one to lead close to a normal life. Testing glucose levels has now become a daily ritual for me. I was resisting my doctor’s advice to get on insulin because of memories of my uncle who had insulin-dependent diabetes and suffered a stroke at a young age which left him paralyzed for the last fourteen years of his life. That was in the 70s when insulin delivery systems were primitive in India. For fourteen years, my devoted aunt looked after his daily care, sometimes with, often without hired help.

After living with fluctuating glucose levels for several years and losing weight due to diet control, I finally agreed to switch to insulin. The result was dramatic. Within a week, I was convinced that the doctor was right. The injections come in an insulin pen with ultra-fine needle and can be self-administered painlessly once every 24 hours since it is slow-release. For me, the doctor prescribed the low dose of 10 units and three years later, the number of units I take has remained steady, albeit with some adjustments. And I can eat everything. In moderation, of course — eating balanced meals has always been our practice. Ice-cream, pies, and whipping cream were not off-limits but an occasional treat. A brilliant solution, thanks to insulin.

*

Since there is no cure for glaucoma, it posed a more serious, ongoing, and uncertain threat. I have been on a regimen of drops since my late 20s as are other members of my extended family. In the last fifteen years, my IOP has been up and down marginally. Around 2006, it rose to 22 (the desirable level is 10-15) — not alarming since changes in drops usually worked to keep it under control. But my doctor referred me to a specialist, a young, aggressive ophthalmologist who thought otherwise and said I needed immediate surgery. What was puzzling was that he insisted I needed Trabeculectomy, a procedure that was risky and carried out when other safer laser-based options have failed. I did not know this at the time nor was I adept at “researching.” You trust a doctor who works for an institution of international repute. The same words, “Listen to the doctor”, would have a devastating result this time around.

To make a long story short, when the bandage on my right eye was removed the day after surgery, I had no vision in that eye. The failure was attributed to a mini-stroke (a central retinal artery occlusion). The doctor was adamant, arrogant, and refused to take responsibility, insisting the stroke had happened after the operation, not during. No apology was tendered. In fact, he was downright rude.

For the next few months, my dominant emotion was outrage. I tried to subdue my anger by writing down an account of what had transpired. After meeting with the director of the Institute who defended the doctor’s position, I spoke to an attorney to whom I had emailed my story. He said in such cases, one would have to prove negligence and in my case this would be hard to prove. In any case, the consent form the hospitals make you sign lists everything from mild headache to death as a side-effect! In sports parlance, they call it covering all their bases.

Every time I replayed the incident or recounted it, it only provoked my anger and this was not doing my heart any good. Even as I retell the story now, I get agitated. I decided to adapt to the new circumstance and get on with my life.

From then on, the left eye had to be retrained to perform the work of both eyes. I continued to work and to drive more cautiously. Initially, my wife drove me to my classes and waited till I finished. My depth-vision was gone. Whether at the dining table or out walking outdoors, distances were hard to judge. The greater concern was maintaining the health of my good eye. Along the way, two laser-based procedures were needed but my peripheral vision began to decrease ever so slightly. I tried to keep my morale up by reading about one-eyed champions. India’s one-time cricket captain played the game with one good eye. And connecting a ball with a bat is the hardest action to perform with one working eye. If Pataudi could reach that goal, I could make at least half an attempt.

Ten years passed before I reached the next optical crisis.

For the last three years, my current eye doctor had been urging me to have an SLT (Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty) to control the pressure in my left eye which had been hovering around 28. And I had been resisting for fear that if anything went wrong, I would be blind. Knowing my apprehensions, he had been patient with me. When the pressure went to 46, he sat me down telling me that NOT doing anything at this stage would surely make me blind. What I agreed to finally, was to have a procedure called Goniotomy which is safer and often done on infants. The doctor said I had made a reasonable choice and assured me it would work to my benefit. He was right. The pressure dropped and remained at an acceptable level.

There was, however, a growing cataract which was making my vision fuzzy and would have to be removed. This time, I took the plunge without hesitation since cataract removal is widely practiced and my doctor had performed hundreds of them. My wife had successfully undergone an operation on both her eyes. It was October 2018. It was a 20-minute procedure under a mild sedative. And while he was at it, my doctor said he would also do a stent implant, which would better manage the pressure. That nano-technology could invent a stent only slightly bigger than the dot on the lower case I, and a surgeon could implant it with such skill in an organ as delicate as the eye, was a marvel beyond my comprehension.

It took four days of recovery time after the surgery causing some anxious moments. But as if by magic, my vision changed from blurry to sharp. I could have hugged the doctor.

*

Now we must retrace our steps to 2008. A more serious health condition was about to emerge. I was sixty-four at this time.

Mumtaz and I were watching a movie as we do every night. Holding hands, we both felt a slight tremor in my left hand. It was the faintest of sensations, a mere shiver. We looked at each other: I skeptically, she apprehensively. I watched for other moments — holding up a text in class, drinking a cup of tea. It was not consistent but a faint tremor was noticeable and it could be stopped with a shift in position or a movement of the hand.

Upon my wife’s insistence, we paid a visit to the family doctor, who referred me to a specialist who said we should wait and watch. It was too early to make a diagnosis or to put me on medication. Ever so slowly but steadily, it continued to develop into what is called an “essential tremor” which is most pronounced in a resting sitting position. If there are no other symptoms, then it is not Parkinson’s. In my case, other symptoms began to develop. Its progression was slow but definite, and the doctor put me on the standard medication for Parkinson’s. Since there is no cure, only slowing it down is possible. And slow down it did while unfolding the full spectrum of its other dreaded symptoms.

I will spare the reader details about how the disease progresses, since the information is widely available on the internet. I continued teaching for another four years after its onset since the pill regimen helped. And I had learnt how to disguise it. I continued my gym workout — movement is essential in Parkinson’s therapy — and my friends claimed they never noticed any shaking when I told them I had Parkinson’s. They were either being kind or had not looked closely.

It is also a cultural thing. A visible social disability is a stigma in traditional societies and the person is to be shunned or snickered at. Fortunately, I was spared that. Indeed, on one occasion at a group reading in New York, my hands shook noticeably and the audience waited patiently while I asked someone else to take over. And the day before, I had given one of my best readings in a different venue. That is the odd thing about this affliction: its unpredictability. A patient may have difficulty walking without support, but he/she can bicycle, and even dance. The progression of the “stages” also varies from person to person. In some patients, the decline is rapid; in others, it takes longer. Everyone is aware of the case of Michael J. Fox and the productive life he has led.

Problems with retrieving short-term memory were shrugged off by my neurologist as part of the aging process. I do see my same-age friends having trouble recalling names of people, authors, places, movie titles, etc. My wife is also showing signs of forgetfulness, but joining together our half-memories, we make a whole!

I am told I have the slow developing kind of Parkinson’s. I continue to drive but avoid the freeways out of an abundance of caution. Muscle weakness has made the doing of ordinary tasks daunting — carrying sleepy kids up four flights of stairs moving heavy furniture, walking up a steep incline, handling metal cooking vessels, and similar tasks.

I continue to write and publish and give readings. I also write book reviews and feel honored when promising young writers ask me to write blurbs for their books. After my retirement in 2012 and four years into Parkinson’s, I published my seventh book titled, Final Cut. Two years later, a book titled Selected Poems was published. A book of essays, reviews, conversations written over a lifetime called, An Arc in Time: Cultural Chronicles from the Last Half Century, is forthcoming now.

Every year as we age, we lose some ability and are able to do less. As in maladies of this order, one has good days and bad. For me, the most frustrating part with hand tremors has to do with writing and typing. I am old-world in this respect: I compose with pen and paper, then, transfer to the computer. One of the symptoms of Parkinson’s is the deterioration of hand-writing: the letters start normal size, then become tinier or squiggly or distorted as the sentence ends. On the keyboard, the keys tend to double-press or if you try a lighter touch, they don’t register at all, considerably slowing down the task at hand.

This has to be poetic injustice: to be deprived of the power one has exercised to define oneself. The singer loses his/her voice, the painter the use of his/her hands, the musician his/her hearing, the runner his/her legs. And yet, people with worse deficits and handicaps have been aided by modern medicine and prosthetics to go far beyond what normal healthy people can do. Above all, it is our determination that salvages for us, some shred of dignity.

When I tell my neurologist my symptoms are getting worse, she chimes in: “For someone who can still do the things you are doing 10 years after the diagnosis, you are doing great.” I want to convince her, but I also want to believe her.

*

About being mortal: what does one say beyond what the world’s poets, philosophers, thinkers, simpletons, jesters, and fools have so eloquently voiced generation after generation for centuries? In effect — we are born, we live, and we die.

Two statements have a particular resonance for me: the first is the standup who serves as the social critic for our times — with a dash of humor. Famously, Woody Allen said: “I’m not afraid of death. I just don’t want to be there when it happens”.

The second is a haunting photographic image of the last Moghul emperor, poet, and calligrapher, Bahadur Shah Zafar. It is 1858. He is 82, and he has been exiled by the British to Rangoon, Burma (now Myanmar). Gaunt and bearded, he is lying propped up on pillows, his head turned sideways looking with a helpless, defeated gaze at the camera. In the depths of his vision, can be seen 300 years of glorious Moghul dynasties of which he is the last representative now living on a pension provided by the British who are eager to impose colonial rule after his passing. He died in 1863 at age 87. What he did as emperor matters less today than the exquisite Urdu ghazals he composed which are sung to this day.

*

Following a daily routine has always been comforting. But now my days have a different rhythm. There is no rush or urgency to drive me; no accountability to an externally imposed time table. Waking up time is variable. Then it is breakfast, shower, gym (yes, I shower before exercising because I don’t work up a sweat. However, if I’m eating a spiced-up dish, beads of perspiration roll down my forehead !), running errands, lunch, making calls to friends and family in India, computer time, some reading, and a most-prized siesta. After a few band stretching and voice exercises comes dinner, news, and movie, until it is bed time.

By necessity, body maintenance forces day-and-night vigilance. Should you be heedless, the body has a way of punishing you. Respect the body and you are given a reprieve. But for a limited time only.

Ultimately, the disease that will claim most of us is aging. I can reel off other afflictions and annoyances that come with age — arthritis, hemorrhoids, constipation (it would appear that nearly every prescription medicine is designed to constipate you as a side-effect; and it seems to be a universal problem inviting public discussion, witness the Hindi movie, Piku), underactive or overactive thyroid, prostate issues, deafness, fluctuating BP, to mention just a few. New maladies are discovered and given names as if they are new stars in our galaxy!

Having enjoyed travel all my life and having been round the globe, I prefer not to subject myself to its rigors any more. I would be lying if I said that my lust for travel has dried up. Drone taxis flying from point to point would be my favored mode of transportation. But that is not going to happen in my lifetime. Until then, I am content to stay in the place where I am most comfortable: home.

But this I know for sure: the older I grow, the less I know.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated