Sunetra Choudhury. Photo: Hridayesh Joshi

Sunetra Choudhury on Behind Bars, an insightful account of the prison life of 13 well-known inmates in India

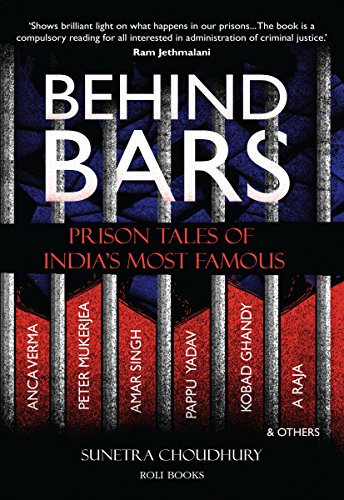

In Behind Bars: Prison Tales of India’s Most Famous (Roli Books), Sunetra Choudhury gives us a peek into the prison life of the rich and the famous. It shows how jails can be a haven for the privileged and hell for the underprivileged.

The book is based on extensive first-hand interviews with some of India’s most well-known inmates, including Peter Mukherjea, Amar Singh, A Raja, Pappu Yadav, Kobad Ghandy, Sanjeev Nanda, Vikas and Vishal Yadav, Anca Varma, Manu Sharma, transgender bar dancer Khushi and terror accused Wahid Sheikh. The book also highlights the trials and tribulations of the undertrials in jails.

“If you steal 1,000 rupees, the hawaldar will beat the shit out of you and lock you up in a dungeon with no bulb or ventilation. If you steal 55,000 crores then you get to stay in a 40-foot cell which has four split units, internet, fax, mobile phones and a staff of 10 to clean your shoes and cook your food (in case it is not being delivered from Hyatt that particular day),” arms dealer Abhishek Verma’s wife, Anca Verma, shares with Sunetra in the book. The book questions the primary purpose of imprisonment: Is it actually reform, punishment or just misusing the system we are a part of?

Sunetra anchors a daily, audience-based show called Agenda and a primetime show on student leaders and elections on NDTV. Excerpts from an interview:

Shireen Quadri: Behind Bars chronicles what goes behind India’s prisons through the stories of celebrity inmates. What triggered the book?

Sunetra Choudhury: Quite simply, I found someone who told me the inside story. I wasn’t really looking to write a book, but I happened to meet Anca Verma. She had just got out on bail and got in touch with me as I was covering CBI. We started chatting beyond CBI, just as two women, and I learnt fascinating details I never knew, of a world where inmates get massages from other, poorer inmates; of the fight to get a western commode; of conjugal visits where women dress up and men just eat. I heard and I couldn’t stop thinking about it so I decided to find out more, which led to more amazing stories and finally, a whole book.

Shireen Quadri: How and why did you whittle down the number of prisoners you write about in the book to 13? Were there stories of other inmates that you had to leave out?

Sunetra Choudhury: It wasn’t a very conscious decision. When I started out, I had a really, long wishlist of those who had spent time in jail. It even had people who had written or documented their incarceration like Binayak Sen and G N Saibaba whose story was written by Arundhati Roy. Then I went about contacting everyone on my list. Some like Sanjay Dutt seemed to have moved beyond their jail time or couldn’t give me the kind of intricate jail diaries that I wanted. Some wanted to tell their own stories like Monica Bedi. I kept at it and along the way found people who weren’t on my list, but were surprise, wonderful additions. At some point, I felt that I had all that I needed and that number happened to be 13.

Shireen Quadri: Was it important for you to have a cross-section of inmates, including transgenders and juveniles, for a holistic picture?

Sunetra Choudhury: Yes and no. Yes, in the sense that initially it was meant to be tales of the rich and famous only. A kind of survival guide as to what happens when the wealthy end up there and how they survive. But I soon felt that it wasn’t enough. How could I do a jail book and not tell the stories of those who were tortured, those who were locked up for years only to be told that it had all been a mistake? So yes, I consciously looked for a story like Wahid’s and I looked for the juvenile home experience too. But I wasn’t just ticking off boxes. The juvenile story was also about documenting young lives in the city, how they live their aspirational lives, at the edge of danger.

Shireen Quadri: Tell us about the process of meeting your sources for the book. Was it easier for them to open up to you since you met them as a journalist?

Sunetra Choudhury: Well, many were sceptical of the journalist tag too. Khushi kept asking me the point of my book because she’d been badly let down by journalists. The news reports that appeared in the Rajasthan press about her gangrape in custody seemed to be victim shaming. They presented the police story instead of presenting her ordeal which is why the police had the audacity to demand a lie-detector test of a rape victim. So, it took her a long time to trust me to tell her story. In the same way, Wahid would ask me why journalists had been so gullible about the 7/11 case. To be honest, I had a tough time defending my tribe. Pappu Yadav was also another subject who thought I wasn’t serious. So he would call me at 7 am or 6 am to his house for interviews. I showed up every day so that I could do the interviews before he went to Parliament or had his public meetings. Eventually, they all figured out I was serious and that’s when it flowed.

Shireen Quadri: Did you want this to be solely about the inmates and what they are subjected to in prisons and purposefully steered clear of the versions of the jail authorities?

Sunetra Choudhury: The book is a jail diary so primarily, it is about the jail ordeal and experiences. But you can’t tell the story without the other side. So the authorities are there too. In the form of interviews of police officers, their chargesheets and court documents. It is all woven into the chapters or in the introduction to the book. I wanted my readers to read it all and then make up their mind about the subjects, all of whom I empathise with.

Shiren Quadri: After reading the book, one of the things that strike one is the sheer difference in the treatment meted out to different sets of people — the rich and the educated enjoy more privileges than the poor and the uneducated. What needs to be done to make prisons give a uniform treatment to every convict?

Sunetra Choudhury: That’s a really, tall order which requires a rehaul of our entire criminal justice system. It requires an end to the corruption which is so much a part of our lives. Only if you end corruption, so that bribes to jail officials don’t matter, will we see everyone getting a uniform treatment. Right now, you have to pay a bribe for everything in jail which is why one famous inmate’s rich parents have built a hotel next door to Tihar in Janakpuri just to service jail officials. Once the jail officials stop taking bribes, it will be the uniform reform experience it was meant to be. Instead of the place where Suresh Kalmadi got preferential treatment by being in the comfortable Vipassana cell during the course of his entire jail term.

Shireen Quadri: Some of the methods of custodial torture are horrifying and inhuman. Do you think there could be more humane alternatives to treat people behind bars?

Sunetra Choudhury: For sure. Why is torture even an alternative? Aren’t we a civilised country that has aspirations to stand at par with all developed countries in the world? Then, why is it that we don’t care that they beat and humiliate inmates. I learnt that jails don’t keep chairs for any public events that inmates attend because they are made to sit on the floor. What kind of a state needs to feel great by inflicting these petty, soul-killing daily humiliations?

Shireen Quadri: What are you working on next?

Sunetra Choudhury: At the moment, I am just working at my day job at NDTV, happy writing news stories and columns, basking in the little notes that those who have read Behind Bars send me. My day job gives me so much material for future books that I have two in mind already but I need to get Behind Bars out of my system first. I’m still obsessing about it and want it to reach as many people as possible.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated