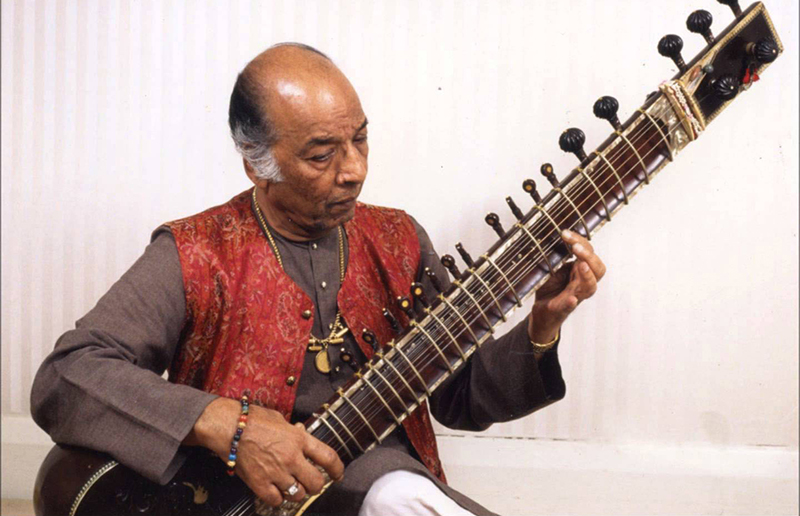

Ustad Vilayat Khan

Any attempt at understanding my father, Ustad Vilayat Khan, leads me to the luminous heritage of his genius. It’s a legacy that lives on: The music and vocal style — gat (the main part of a Hindustani raga performance following the alap), barhat (the development of a raga) and jor (an intermediary musical bridge section that comes after the alap) — pioneered by Ustad Vilayat Khan are followed by many artistes even today. He belonged to a different league of men — a league that included the likes of Beethoven and Chopin. I say this not just for his mastery over the sitar, but because he changed the structure of instrumental music in India, at least the north Indian classical music. This is not just a daughter’s eulogy or filial piety, if you will, but this sentiment has been echoed by several artistes.

Sitar and Surbahar (bass sitar) was in his genes for six generations, and so he was not only born into it, he was also born for it. Son of illustrious sitarist Ustad Enayat Khan (1894-1938) and grandson of Ustad Imdad Khan (1848–1920), abba was the torchbearer of Imdad Khani Gharana or Etawa Gharana, named after a small city close to Agra where Imdad Khan lived.

Ours is one of the oldest gharanas. It was during abba’s grandfather’s time when the recordings were done for the first time. Imdad Khan’s recordings were one of the first done in India back then, when only the greats were recorded. Incidentally, there are many popular gharanas, with generations of music behind them, but hardly any of them have their forefathers’ recordings of Imdad Khan’s time.

As an inquisitive child, abba was naughty, so much so that his mother would have to discipline him a lot to rein him in. A child prodigy, he recorded his first disc at the tender age of 9 with his father. However, destiny had other plans for him. Abba lost his father when he was just 10-year-old and he had to continue his musical training under his maternal grandfather (naana), Ustad Bande Hassan Khan and maternal uncle (maamu) Ustad Zinda Hassan Khan, both eminent khayal vocalists. And, yes, there are recordings of them too. Abba always said that if he had not lost his father, he would be playing the sitar in the same traditional style as his forefathers.

Every artiste tends to get influenced by every kind of music and everything that’s around him. A genius is one who can absorb things from varied areas. It will be a disservice to many others if I say only a few had an influence on Ustad Vilayat Khan’s music. But the greatest influences on him were his own forefathers — Imdad Khani Gharana — and his maternal family of vocalists. And, thus, he combined the two and his gayaki (rendition) style was born. The tonal quality of the sitar and the tone of his tunes and compositions are very much similar to his maternal grandfather and maternal uncle’s singing. When my grandmother, Bashiran Bagam, watched him transforming into a vocalist for a period of time, she told him, “When I die, how will I show my face to your father if I make you adhere to my father’s family legacy of vocalists rather than my husband’s family’s legacy of sitarists?” My grandmother was responsible enough to guide my father to carry forward the legacy of the celebrated Imdad Khani Gharana of her husband’s family. But Ustad Vilayat Khan created such a combination that though most artistes follow him no one comes close to his brilliance. This is the reason every artiste has adored and loved him. He knew he was revered and loved by one and all and was grateful to God for it.

As a child, my father had a great interest in exploring and developing everything about sitar. This led to the genesis of Ustad Vilayat Khan’s sitar, which is used by his followers. He tweaked the instrument to evolve and be able to produce the kind of music he wanted it to play. If you see the documentary I made on him — Spirit to Soul — you’ll see the various changes he made and more importantly — for the “reasons” he made them. Any experiment is not successful in music or otherwise until others emulate it. Had Penicillin not worked on people, it would not have been considered a successful invention. Similarly, Ustad Vilayat Khan’s vocal style on instrument was the first-of-its-kind in the history of Indian classical music. So, it is no wonder that he had to make these changes in the sitar to produce his kind of tonality. The recent stamp release of Ustad Vilayat Khan by the President of India is an acknowledgement of abba’s genius as a luminary in the field of Indian classical music.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated