The International Writing Program is the oldest and largest multinational writing residency in the world. (Below) Writers gather for a session during the residency. Photos: writersworkshop.uiowa.edu

When I was accepted into the International Writers Residency at the University of Iowa, I entered into a crucible. Was it now time to come out of the closet, own my place as a writer and confidently spend this Residency surrounded by what I believed were ‘real writers?’ I convinced myself that I could easily slip through the system of engagement with fellow participants if just stayed in my safe place. My room, my enormous chair. But, I did not succeed.

In early August 2018, I prepared to enter the International Writers Residency at The University of Iowa. I imagined a room somewhere, with one enormous chair and hours of solitude to write. I had never thought of myself as a writer. In my tiny community of Indian migrants to South Africa, a famous catch-phrase would ring:

“Better – Doctor. Not Writer.”

But a marriage to the medical field and a very secretive flirtation with writing found me fumbling and stumbling my way into writing a successful debut novel (What About Meera, 2015). Medicine would forgive me and take me back, I told myself, once the heady lover had spit me out. I was afraid. I morphed my fear into an air of nebulous detachment. All I knew was the safe career of the medical profession, and I had written my debut novel with a sense of guilt, hiding it from my family. I felt like a fraud, entering the Program, not having any qualifications in Creative Writing or Literature in any way. It surprised me that my debut novel was even published by a large publishing house and went on to win awards. I never felt comfortable accepting the accolades, and played this achievement down in the face of my “real” career. But, when I was accepted into the International Writers Residency at the University of Iowa, I entered into a crucible. Was it now time to come out of the closet, own my place as a writer and confidently spend this Residency surrounded by what I believed were “real writers?” I convinced myself that I could easily slip through the system of engagement with fellow participants if just stayed in my safe place. My room, my enormous chair. But, I did not succeed.

I was one of thirty five. It was never a moment that we were allowed to forget how special we were to be there. I did not feel special. I felt like a charlatan. Unknowingly, much like Alice falling down a rabbit hole, I had stumbled into the Writers Residency. And always a rag-girl, without the possibility of a Henry Higgins in sight to educate me in the elocution needed to stand around in black polo neck jerseys and throw around quotes from Borges, I retreated further.

I must not be too hard on myself. I am a product of a wasp’s nest of stereotypes, and coming from a world where a bank manager guffawed when I applied for a home loan and told him my profession was “writer,” I just went ahead and checked the other box on the form. There was no check-box for writer. There were five boxes for Medical Professionals.

“Writing is in my blood,” is a rhetoric I reject. It sounds too parochial, and conformist. An idiom thrown around too often, and often too easily. But, truth be told, it was in my blood, yet I lacked the space nor the conviction to admit to it. From a dry desert of deep hunger, in a city — Durban — that would not allow me to feed myself on this artistic leaning, arriving in Iowa City I was confronted by a frightening smorgasbord of people who actually took this writing thing seriously. I had fallen head first down a rabbit hole, and I took the pill that made me smaller.

Somewhere between the worst of jet-lag and the sounds of many different accents in the corridor outside my hotel room, I settled into my one enormous chair, dreaming of Orhan Pamuk and the little urban legend about his participation in the self-same Residency, where no one ever saw him. Evidently, he had found a room somewhere, and settled into it, never showing his face until his novel was done. A Venezuelan writer on the Program with me even coined the term “Pamuking” to be used when any of the writers were not seen for days, and had locked themselves away. So, I decided, the safest way for me to come out the other side of this Writers Residency was to do some serious “Pamuking.” Plan A: Retreat into the room. Check. There was no Plan B.

Every morning, there arrived a ghoul at my back, a word I had not factored into the amazing word count I would never rack up as I coddled myself on coffee. There came the inexpungible word “camaraderie.”

Now, I loved this word simply for the way it sounded. To me, it still is one of the best sounding words, simply for its phonetic ability to make you repeat it over and over again. Much like the word broderie, a rich, multi-textured lace made up of many different needle strokes. How linked those two words are. I soon discovered the different strokes for different folks, and my Pamuk dreams of seclusion went head first into the Iowa River that I paced along every morning.

The International Writers Program at the University of Iowa had been in existence since 1967 and over 1400 writers from more than 150 countries have been in residence as participants. This information, received from a quick Google Search, did nothing much to begin to explain this Residency in all its complexity. Another Google search that attempted to find scholarly articles on the relevance of Writer Residencies, and the secret alchemist formula that makes for a successful one as a personal endeavour for a writer, revealed nothing much. Wading the waters of not knowing how to do this, found me creating my own way on what the Residency would do for me. And to me.

Anticipation of the name turned out to be a misnomer, if only in my own personal opinion. And, in this Residency, it was the construct of own personal opinion that began to become the keystone that us thirty-five writers used to define our place, our roles within a tenuous thread. Some of us came armed with baggage that extended beyond warm winter coats, for we could never quite Google the unpredictable weather of an Iowan Fall. Some of us called it autumn.

Very early on in the haze of jet-lag and the seduction of the beautiful Western world, there came an incongruous humidity we did not expect in Iowa. The melting and melding had begun. Each bleary-eyed Resident emerged with his/her own personal style. And this style was not often as obvious as we made it out to be. Somehow, the unpredictability of it all eluded me, chasing away the pre-conceptions I had arrived with. I believed that this would be some sort of Summer Camp — where the cool kids would band together, the geeks would fidget with gadgets and the rebels would go looking for a cause. I imagined the lines that would divide us. Country and language started out being my go-to boundary that would splinter the herd.

Rather quickly, over a breakfast that initially was staccato, where we all would arrive fully dressed and smelling fresh, I found that I was wrong. Language, and country, did not create the tables of dominion. Neither did it become age, nor gender. Girls did not aggregate with girls, sitting in giggling sorority groups as I had imagined. Novelists did not bunch up with novelists, poets with poets. Soon enough, only a week had passed and arrival at the breakfast room in pyjamas and messy hair became the order of the day. Yet there was no ordered way in which we congregated.

I stopped at that point and asked myself, quite literally and out loud, what is the defining quality of this group that would sub-divide and sub-let space in each other’s lives for a gaping maw of ten weeks? It is a thought process that served to drive me slightly batty. Why was I constantly analysing, and not experiencing? Was I writing academic articles in my own head, when I should have been taking in the literature of a city that walks on America’s inaugural UNESCO City of Literature? I refer to the entrancing metal plaques embossed with words in the sidewalks of Iowa City.

I recalled a wonderful quote I had read from a lecture spoken and then penned by Susan Sontag, on the occasion of my fellow country-woman Nadine Gordimer (1923-2014) being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1991.

“Literature involves. It is the recreation of human solidarity.” Sontag had said, and in a country where solidarity was the vanguard of a fight against apartheid, this recipe of solidarity was something I tacitly understood. What I was yet to understand through a process that took ten weeks was how to do this unanimity thing.

First, I knew that I had to stop. I really had to stop. I knew that all this taciturn reflexivity was robbing me of beautiful sunrises and even more beautiful conversations. Often the best conversations about art, life and nonsense happened in the least conspicuous spaces. They didn’t happen on formalised panel discussions or question-and-answer sessions in large lecture halls. They happened in the laundry room of the hotel. They happened in dive bars, late at night. They happened on a white wrought iron bench behind a chapel outside the hotel where writers would sporadically appear, to break the university rules and smoke cigarettes at 2 am. I missed the best parts. Hiding as I did, in my own head, fumbling around for a place to call my own, I did disappear down a rabbit hole and it was a lonely one. I loved that bench too late.

I trouble-shooted to a safe place as an observer, a voyeur, feeling my role as one placed there to observe a group, and to hearken every action of this group to the psychological theoretical frameworks of Albert Bandura and Foucault’s Panopticon. Discernibly, there are dynamics within any group. Watch a group of kindergarten children in a playground and you will probably learn more about human nature than the entire epoch of Human Psychology 101 put together at the Iowa University Library. These writers on this Residency were neither kindergarten toddlers, nor were they subjects for me to add to an already overburdened research canon that had just said far too much about nothing much at all.

Of course, you don’t need a psychology degree to hypothesise that groups will splinter, form and then re-form again like some form of mercurial liquid in the palm of your hand. There is no quantifying it. And reflecting on it ethnographically is actually rather like entering into voluntary schizophrenia. Am I the watcher today, or am I the participant today? Am I the catalyst today or perhaps, let me just be a Resident today?

A few of the Residents came from an initial incarnation of non-literary careers. But I certainly did not see the geological engineer in the group digging around our midnight discussions in the common room looking for crude oil. Nor did I see the human rights lawyer attempt to take on cases of subjugation. Why then, did this psychologist, who came to Iowa looking for an enormous chair end up with a couch?

Was I ostensibly encouraging the Residents (who were by week three becoming family), to sit on my couch and tell all? Did I want to break each one down into their bare bones so that I could understand them and become them?

No. It was none of those things, and I know it only now. I did it because I was insecure, and I wanted to understand what in the world I was doing there.

I suppose I hypothesized that if I didn’t break this group down into archetypes in my own head, then the familiarity of how to navigate my way within this group would be lost to me. I think that suffering this nasty affliction cost me one of the greatest joys that the International Writers Program offers, and that is enjoyment. Pure and simple, there is no greater place to be than in a room full of slightly inebriated writers, poets, dramatists and artists, who banter for pleasure and not for profit. And profit is not always monetary. Profit can be comradeship.

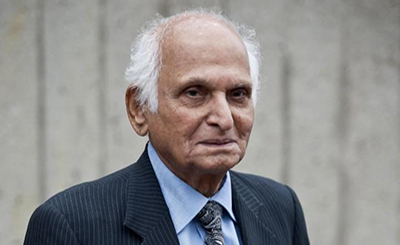

One morning at the river, after I had returned from yet another brow-furrowed walk, I met a writer and Literary Professor from Cyprus, Stephanos Stephanides, 70, a man who I timidly got to know over passing conversations that were so spontaneous, but almost planned in that they always engaged the very topic that occupied my mind. I am never one for mysticism but as the Iowa River sparkled, I noticed that the currents were too wayward, moving in one direction for a minute and then suddenly veering off in another. There was no predictability in how this water would move. Maybe, Steph recognised this churning in my mind.

I paused to ponder, digging into my memory banks for scientific explanations of currents and physics. Steph came to stand next to me, and simply remarked:

“Isn’t it beautiful?”

I shook myself off like a dog after rain. I realised that I had not even noticed the beauty, lost in analysis. I told him this. He laughed. We began a conversation that bloomed into an almost daily routine where I revealed to him my puzzled fragility. He told me stories of how he had once been teetering so dangerously on the edge of drowning in academia, with its allure of entering into a permanent state of auto-ethnographic investigator, that he had to physically step away from the world of research. He said that he was losing his poetry. He said that each time he attempted to spend his time recording his memories and then academically analysing them, he began to lose those very same memories. He was losing his poetry.

My realisation that I was doing the same did not come easily. It was my ego that had to be guillotined first. My titles, my science and medicine. My enormous therapist’s chair, where I felt much like it had been a throne that a very scared queen sat on.

As I reviewed my extensive journals that I kept about myself, the writers and the flurry of activities, I slowly began to see that a cynical eye had revealed itself. This eye of jaded sarcasm reared its head in my writing. Nothing really appeared to me as a pure and simple act, a sharing, a moment in time. It was always the whys and the wherefores. This slow recognition, with daily increasing fellowship amongst my Fellows, prompted a disquiet within me. Should I have simply retreated into a darkened room? I tried that. Claustrophobia won out, but my darkened room was persistent, and transmogrified into witching hour walks along the bridges of the Iowa River. I was losing my walls, but it was not easy.

Still, an air of watchfulness remained. An air of separation. This detachment was neither snobbery nor shyness. It was just an irritating habit of constantly needing to reflect and analyse. When the time came for muscles to be flexed — and I am talking now of panels and readings where we really saw the writers transform from dishevelled breakfast room siblings and tipsy common room revellers, into serious panellists with prepared speeches on all things literary — I almost felt my ears rotate to every single word that each one uttered. Am I looking for the Holy Grail? What makes this person a writer? And why do I not feel like one?

I never did find my answers in books and psychology. Funny how the things you learn are not from the books you read at night in a City of Literature. I thought of Steph, and I realised, poetry had been leaving me, too. I just didn’t know it had once had me, and wanted me back.

How stubborn was I to find and place my voice in that cacophony and throw my hat into the ring! Who was I? Just a little-known, one-novel writer from a small village in Africa. I felt the inadequacy of my own role as a writer, that I felt the need to suck the souls of other writers. In my quest to place myself in this group, I harassed those that were indeed confident enough in their craft not to dissect it to smithereens. I recall badgering a playwright from Argentina to a point of his ultimate frustration to teach me how to write plays. What a ridiculous request! Learn to write a play in two hours or less!

Neither poet, nor screenwriter, neither this nor that, I had read through the introductions and lengthy portfolios of all my fellow Residents and wished to be swallowed up by the Earth. And when one loses a root that shows you your place, psychology will provide you the formula. And theorise I did. Nothing escaped my endless theories that veered into Constructivist Feminism theory into the murky waters of the Testimonio of Rigoberta Menchu. Is it a creature called a zombie, who, having no soul, becomes a soul-sucker?

On a reading visit to the Davenport Museum with two wonderful writers from Israel and Ethiopia, it was a peek at an exhibition on the Wizard of Oz (1952) that shifted a little cogwheel in my head. Looking at that Tin Man, that Lion and that Scarecrow, I finally knew that I was all three. And much like all three, the answer to acquiring what I had come onto the yellow brick road for was found not in the destination, not in the Wizard, not in the Philosopher’s Stone, but in the journey of the road itself.

I often took long walks with Akhil Katyal, a poet from India. He was highly intuitive, to the point where he probably observed my reclusiveness and literally came banging on my door almost every afternoon with his huge smile and his wagging finger.

“Get out of those pyjamas, and get out of this room. We are walking!” he would say, and I would comply, actually beginning to await those knocks on my door.

There was no destination for our walks, no special and important place to be, no points to be discussed. We just walked. Everywhere. The streets of Iowa City began to expand in my vision. The world did not just consist of the library and the grid of restaurants. We meandered, lazily, and found ourselves crossing fields filled with dandelion weeds, eventually ending up two hours later at Goodwill, where we tried on wigs. We drank frozen mango juice and sat on benches, saying nothing much. We sang old Bollywood songs outside The Hancher auditorium, waiting in line with The Senior Citizens Club to watch the Iowa City Orchestra and University Choirs perform a rendition of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony (1902) that unlocked my heart like the wings of a blue butterfly.

A strange thing though… almost every walk of ours would find me tripping over and almost falling face down onto the clumpy grass mounds of Iowa City. Laughing it off as having inadequate soles, I realised one day that I was so consumed with the analysis of the “event” of meandering to no place in particular with this poet, that I had lost out on the gift of meandering. Akhil was on to me. Telling me like it is, he would bring my mind back to the present moment in true poetic style of simple enjoyment. I told him, “Just maybe I am too busy watching out for the cracks in the road.” Well, he told me, I was too busy looking for darkness, when the world around me was bright yellow.

The International Writers Program was a span of experiences, and the most significant of it all was not actually writing. There would be time enough for this lap-top humping when we all would be sprinkled on the levanters, back to our lands. It was all about being fully present in every moment, without artifice and without analysis. It was about the beauty of a borrowed guitar and impromptu songs.

Eventually, I became a writer. Later than earlier, in that ten weeks. But it did happen. When I stopped, when I ceased from inhabiting the space of desperately wanting to be seen as one, I became a writer in Iowa City.

And I did find that there is a room somewhere, far away from the cold night air. And this room did not have to conform to the archetypes of the solitary angry writer dryly cutting everything down to bones. It was a warm room and it was filled with the combined daily lives of 35 people. The angers, the nostalgias, the memories, the tears of Skype chats home, the guilt, the laughter and the flow of beautiful words. I found the room. And I found the enormous chair. I did not have to sit on it alone.

A few days before all the writers on the Program left Iowa City, I stumbled upon a quote written on the noticeboard of the Public Library. It was a quote by Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711-1776), and it read: “Your corn is ripe today; mine will be so tomorrow. “‘Tis profitable for us both, that I should labour with you today, and that you should aid me tomorrow. Here then I leave you to labour alone; you treat me in the same manner. The seasons change; and both of us lose our harvests for want of mutual confidence and security.”

I scribbled the quote into my journal, although now, I do not need that reflective journal any longer. I might just throw it into a river in Africa.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated