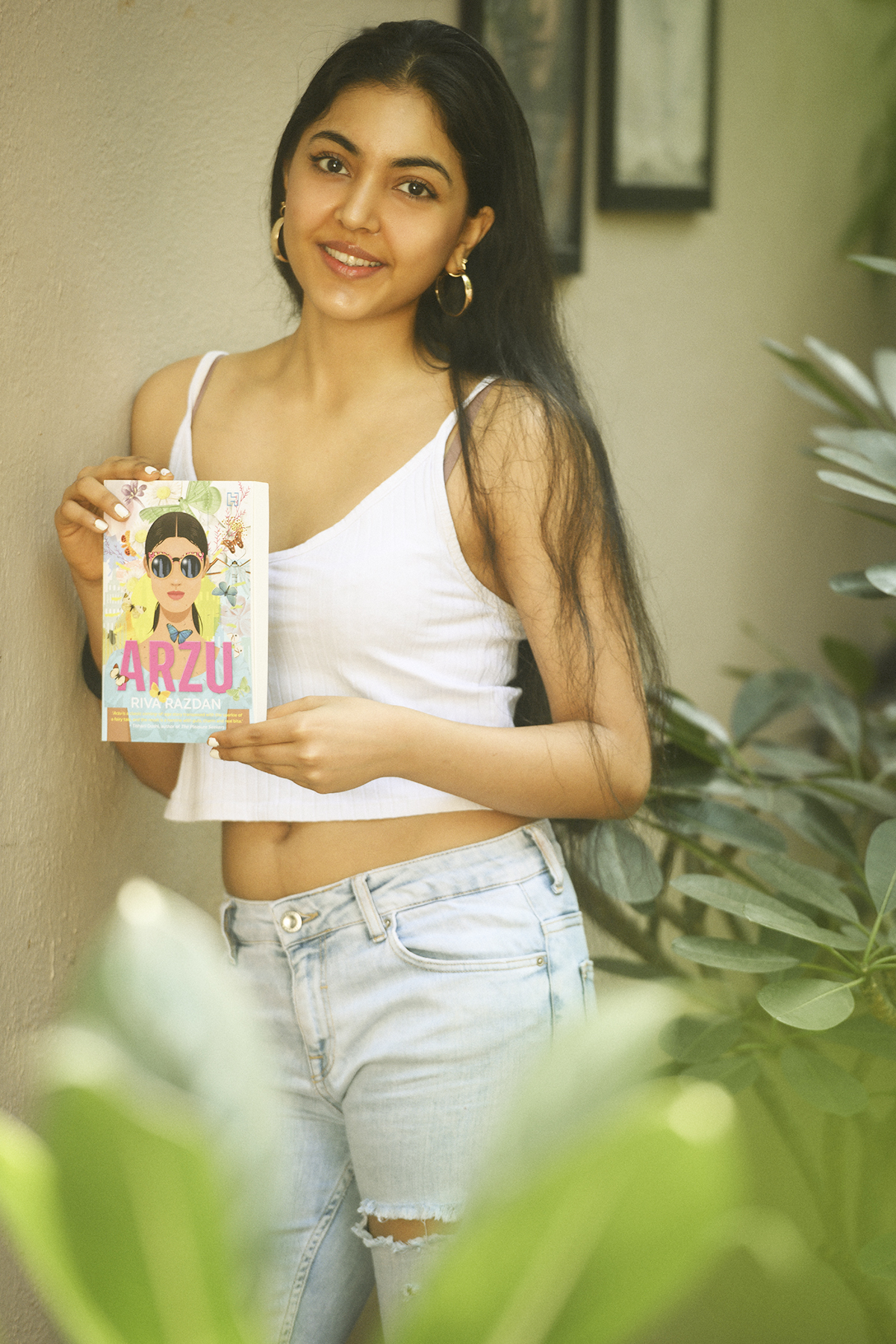

Riva Razdan, author of Arzu (Hachette), a novel. Photos courtesy of Hachette India

I am determined to be part of a culture of storytelling that places Indian heroines at the center of the narrative. I hope that young girls will be able to find, in my books, protagonists who look like them, who talk like them, and who grow to be capable and authentic heroines that the readers are capable of being

One of my earliest memories of joy is wrapping myself in my grandmother’s lavender chiffon dupattas and enacting the latest story she’d told my brother and I. Others could be present or not, I’d continue on, Cassandra-esque, enjoying being the empress of my own make-believe world.

My little imaginings started to be honed into more formally presented visuals in narrative in the second grade, when we learned the art of the essay. My ‘I wish I had a dog’ was received very well and given rave reviews by family in Bombay and extended family in Delhi. I’d even perform it at the slightest request and bark at the end, if I liked the audience enough.

But that was the end of my illustrious literary career in school. It burnt brightly, but burnt out quick. In a class of forty students, in a grade of 250 other children, all of whom are planning to do something practical and truly illustrious with their lives, being a writer or an artiste, just seemed...silly. It didn’t matter that my family was also made up of writers and artists. They seemed a bit silly too, always talking about films or literature instead of the class parent politics at the PTA. I didn’t want to be deviant. So I moulded myself to fit in with the other 250 kids at school, till the dupatta-draped little empress disappeared entirely.

I never signed up for elocution or dramatics or essay contests again. I was going to be a lawyer. Safe and slottable and because my math grades were never good enough to consider medicine. I still loved literature and film. I still found my identity in the pages of empowering prose by female authors like Meg Cabot and Jane Austen and Jacqueline Wilson. I still secretly hoped to conjure compelling worlds of my own, making magic out of the urban Indian milieu.

But I didn’t tell anyone. Hell, I didn’t even tell myself that I was going to be a writer. To be honest, I still have a hard time introducing myself to strangers — bracing myself for the inevitable eyeroll. It’s a little bit easier now, with my book Arzu (Hachette India), out. But the comparisons to Rupi Kaur begin almost immediately. Not that I’m complaining. She did outsell Homer last year.

It wasn’t until high school, till I started applying to colleges abroad, that I realised that there are spaces in the world where you’re encouraged to be different. You’re supposed to stand out. And the only way in which to do that is to start being honest about who you are. I started to be honest in my applications about what I wanted to do with storytelling. I got a scholarship to college to study it.

And there I found that the arts were a discipline, not an indulgence, meant to service others. It was meant to spark discussions and further dialogue. I committed myself wholeheartedly to understanding how the others before me did it. Ken Follett, Margaret Mitchell, Aristotle. I learnt that cultures were built and rebuilt over the stories their people told themselves. That storytelling isn’t just a necessity, but a cornerstone of society. And those who ignore this truth, do not even know that they are being acted upon by social scripts handed down to them years ago — social scripts that may no longer serve them. I, for example, was trying very hard to play the good Indian girl all through school. A script I had doubtlessly imbibed from hours of watching bad TV with pretty/dutiful Indian doctors, lawyers and wives. (Give it up for StarPlus, am I right?)

Not that there’s anything wrong with any of these occupations, but the overall message seemed to be for women to toe the line in terms of societal expectations. In all the mainstream Indian fiction I consumed, it seemed that the girl who wanted to be a DJ or an artist or an actress, was also the drug-addicted problem child. The black sheep of the family. And the story was never about her. It seemed as though taking risks as a girl, immediately shoves you to the edge of the frame or the outskirts of the narrative. Meanwhile, the West was embracing girl stories and celebrating their radical heroines. Hunger Games became a bestseller globally and Katniss Everdeen a household name. From her, I, and a lot of my friends learned that it’s alright to be fiery and powerful. From Normal People by Sally Rooney, a generation of girls learned that it’s okay for us to feel desire. All of these little confessions we allow ourselves, help us inhabit ourselves a little more. They help us make decisions that serve us, instead of serving others.

Our culture today is still shaped by the movies we watch and the books we read. But while the young Indian girl is very much a part of our culture, there isn’t much fiction that is documenting her experience, romanticising her adventures or encouraging her to inform herself and make her own choices. Where is India’s Katniss Everdeen? I meet her often enough at coffee shops or in offices. Why hasn’t she made it to literature or the movies yet?

I am determined to be part of a culture of storytelling that places Indian heroines at the center of the narrative. I had to delve as far back as Sita and Draupadi to find the courage to start draping myself in naani’s chiffons again (metaphorically speaking) but I hope that young girls will be able to find, in my books, protagonists who look like them, who talk like them, and who grow to be capable and authentic heroines that the readers are capable of being. I hope it helps them, a little bit, in finding and owning their own spark, as it took me too many years, and too many lies before I rediscovered my own.

This piece is part of The Women’s Issue, curated by Shireen Quadri

Comments

*Comments will be moderated