(Above and below) The baoli at Hazrat Nizamuddin. Photo courtesy of Niyogi Books

The baoli in Hazrat Nizam-ud-Din Basti or Nizam-ud-Din West was built in AD 1321–22 during the lifetime of Khwaja Nizam-ud-Din Auliya

As the story goes, the construction of a baoli in Ghyaspura (now Hazrat Nizam-ud-Din Basti or Nizam-ud-Din West) was underway, when Sultan Ghiyas-ud-Din Tughlaq’s ambitious project Tughlaqabad began. Tughlaq forced all the available labour to work only for Tughlaqabad, and the work at the baoli was stalled. Khwaja Nizam-ud-Din Auliya, fourth in the Chishti order of Sufism in India, requested masons to work at the baoli during late hours after their shift in Tughlaqabad. He was a beloved of everyone, so the masons agreed to do the job. One day, a supervisor found one of the masons sleeping during his day shift. Upon inquiry, the covert double shift plan was revealed. Tughlaq got so angry that he prohibited the sale of burning oil in the region. Without oil, earthen lamps could not be lit, and without light, no one could work at night. It is said that Hazrat Nizam-ud-Din Auliya cursed the fort of Tughlaqabad and suggested his disciple Hazrat Nasiruddin to attempt lighting the lamps with the baoli’s water. People say that Hazrat Nasiruddin, who later became Nizam-ud-Din’s successor, illuminated the village by lighting lamps filled with mere water. He was thus given the title of Roshan Chiragh-e-Dehli (the light of Delhi). The water of this baoli is considered miraculous thenceforth. One variation of this story is found in the record of Zafar Hasan, where he mentions that when Ghiyas-ud-Din prohibited the sale of oil in the region, Nizam-ud-Din complained to Sayyid Muhammad Behar, who was building a mud wall. The latter, angered at the emperor’s persecution of the saint, demolished his mud wall and exclaimed, ‘I have destroyed his empire!’ Other writers attribute this incident to Hazrat Nizam-ud-Din and say that the saint cursed the city of Tughlaqabad with the words, ‘Ya rahe ujjad, ya base gujjar’, implying that the city will either remain in ruins or be populated by herders.

This is a story that the people of Delhi will narrate to you with pride. However, such stories are often regarded as hearsay and discarded by credible historians. But they remain an important part of the oral traditions of a community and say a lot about the era. Such stories sometimes also fall prey to Chinese whispers. Going by the recorded information, many historians and archaeologists noted that this baoli was built in AD 1321–22, during the lifetime of Khwaja Nizam-ud-Din Auliya. Khwaja Nizam-ud-Din started removing the mud with his own hands, thus marking the beginning. In 1379, one Muhammad Maruf, son of the minister Wahiduddin Qureshi, built mud houses in the nearby streets of this baoli and inscribed the name of Feroz Shah Tughlaq on a stone slab. Sir Syed Ahmad Khan mentions seeing this slab (mid-nineteenth century). He also says that there are several graves and dwellings around the baoli. The wall around the baoli (and the shrine) was built by Nawab Ahmad Baksh Khan of Ferozepur. To the south of the baoli, there is an arcaded chamber adorned with pierced, red-sandstone jalis. Originally, these arches were not sealed with jalis and were just covered with small stone parapets to prevent one from falling into the baoli. While experts like Maulvi Zafar Hasan find this structure of no interest, I think that this chamber is one of the most important aesthetic elements of the baoli. The baoli today is recognized due to this chamber and its five windows. Other important structures comprising the baoli wall are the tombs of Fatima Bibi and Zuhra Aga in the north-west corner, Chini ka Burj to the west, Bai Kodaldai’s Tomb to the west, and a building called Lal Chaubara to the north-west. Some of these buildings are dilapidated beyond recognition, and a few even lost. On the eastern side is the passage to enter the dargah. The baoli is accessed through a small gate from the north.

Further reference to the slab mentioned by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan can be found in the book by Maulvi Zafar Hasan mentioned before. While Zafar Hasan clearly states that there are no inscriptions on the baoli, he referes to a slab in the southern arcaded building which matches the description by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. The translation, as given by Zafar Hasan, follows:

In the name of God who is merciful and clement.

In the reign of the great king, the fortunate monarch and the descendant of Adam,

The support of the religion of Ahmad (the Prophet), Firoz Shah who is a king, Lord of the happy constellation and the greatest of sovereigns,

The slave Maruf was assisted by God, and he made firm the foundation of this building,

In the neighbourhood of the tomb of Shaikhul Mashayakh Nizamul Haq-Wa-deen, the pole star of the world,

Wahiduddin Quraishi, my father, who was a companion of the devotees (of Shaikh Nizam-ud-Din),

And who was a confidant in the secrets of the friend of God (Nizam-ud-Din) of good faith and sincerity,

When he brought me before the chief of the world (Nizam-ud-Din), he (the latter) took me in his arms and named me.

And the Shaikh with the breath of Jesus named me Maruf in his own utterance, in this world.

I hope through that auspicious utterance to attain to fame in the next world also.

Read the date of the completion of this building as a welcome when you visit this place.

It was seven hundred and eighty-one from Hijrat when this building was erected. God knows best.

This slab no longer exists. But the empty space (usually meant for such slabs) outside the south gate (towards the dargah) of the baoli chamber confirms the story.

As you enter the dargah complex from the northern gate, the first structure you encounter is this baoli. It measures 123 feet by 53 feet internally. This baoli has one similarity with the Kotla Feroz Shah Baoli. There is no separate well (like other baolis), but the tank is the well. One major difference from Kotla Feroz Shah is that Nizam-ud-Din Baoli is not covered.

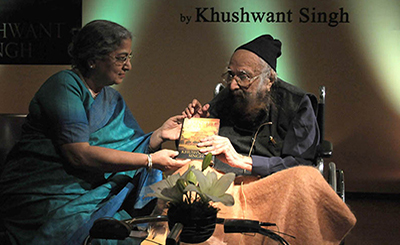

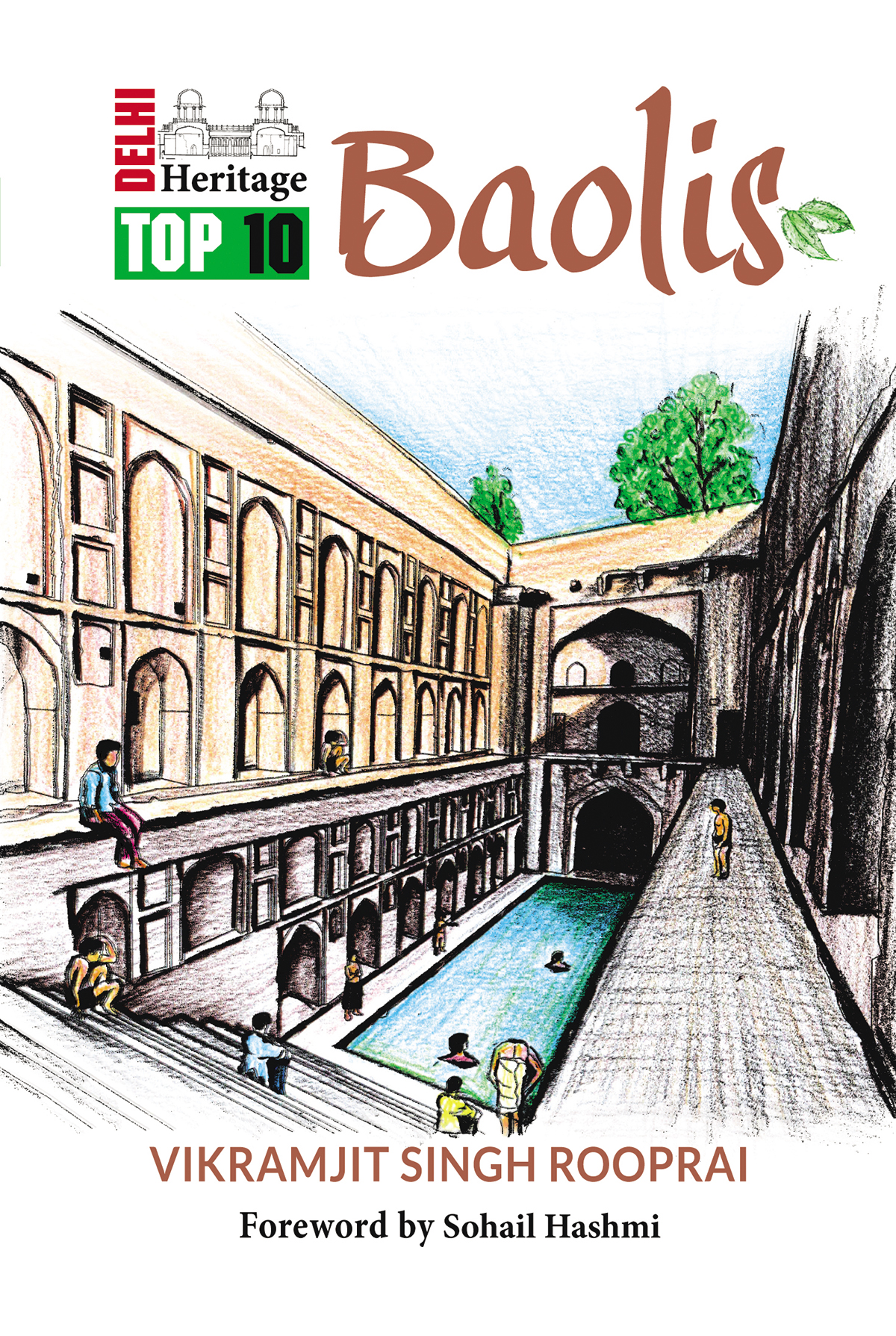

Excerpted from Top 10 Baolis by Vikramjit Singh Rooprai, published by Niyogi Books. The publishing house’s Delhi Heritage Top 10 series is a comprehensive guide to Delhi’s heritage icons and architectural gems. The first volume in the series, Top 10 Baolis by Rooprai, delves into the fascinating history and the great significance of forgotten, subterranean, man-made water structures, commonly known as baolis or stepwells. The book walks us through the top ten baolis, with two special mentions. Besides giving a vivid description of the functioning and revival of the baolis, the book also focuses on the social importance of each structure. The work is an outcome of a five-year-long research from various archives, and contains historic as well as modern photographs along with architectural drawings.

Excerpted from Top 10 Baolis by Vikramjit Singh Rooprai, published by Niyogi Books. The publishing house’s Delhi Heritage Top 10 series is a comprehensive guide to Delhi’s heritage icons and architectural gems. The first volume in the series, Top 10 Baolis by Rooprai, delves into the fascinating history and the great significance of forgotten, subterranean, man-made water structures, commonly known as baolis or stepwells. The book walks us through the top ten baolis, with two special mentions. Besides giving a vivid description of the functioning and revival of the baolis, the book also focuses on the social importance of each structure. The work is an outcome of a five-year-long research from various archives, and contains historic as well as modern photographs along with architectural drawings.More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated