When our daughter was about to be born, I chose for her a short name, Ila. Ila’s mother is Muslim, I am Hindu. We had got married when our two countries, India and Pakistan, were fighting a war. Ila is a Hindu name; it is also the opposite of her mother’s last name, Ali.

Ila Ali. A friend of mine said it would be a name that would sway in the breeze all day. I had noticed that it formed a palindrome. Ila’s name mirrored her mother’s, and yet kept its difference. I liked that.

Which is all to say that even before she was born, Ila had become, like many other kids, a site of complicated, and often silly, fantasies on the part of her parents.

Ila is now six. A few days before she was born, I chanced upon an essay by Raymond Carver called “Fires”. It is a memoir produced, I suppose, in response to a question about literary influences. In a characteristic move, Carver declares that more than books and writers, it was other things in his messy, real world, that had affected his work. In particular, his children. The memory of those years, when his kids were growing up, still bothered Carver. Sitting in the basement of my in-laws’ house in Toronto, while waiting to become a new father, I read the following lines: “I have to say that the greatest single influence on my life, and on my writing, directly and indirectly, has been my two children. They were born before I was twenty, and from beginning to end of our habitation under the same roof — some nineteen years in all — there wasn’t any area of my life where their heavy and baleful influence didn’t reach.”

It is a searing little essay. Carver describes the desperation of his younger years, working at one, sometimes two, menial jobs and trying to put food on the table for his family. He describes his struggle to write. He wrote short stories because there was never enough time to write anything longer. His despair soon begins to feel like a dark liquid pooling on the page. You feel the writer’s pain but, of course, you can also imagine the children drowning in that misery.

Around the time that I first read “Fires”, I was also starting to draw the outline of a first novel. I cannot remember now whether it was Carver’s essay which led to this decision in my mind, although I remember reading that piece more than once that summer, but as I played with the outline I began to think that I would write about the birth of my daughter. My wife underwent a long, painful labour. The novel began with a man in a prison near my hometown in India. I tried to imagine him witnessing a birth in a prison, not a human being giving birth, but an animal. Say, a dog. Now when I look back on it, I wonder whether some of Carver’s “dirty realism” (or what Tess Gallagher has called his “benign menace”) hadn’t crept into my presentation of Ila’s arrival as an animal birth witnessed in a prison. In any case, when the novel was published, the scene I have described above found its way into its pages. But there were many times during the writing of the book when I wished I had more time to write. Perhaps all writers complain about time, there is never enough time, and in the years following that first encounter with Carver’s essay, I have often gone back to it like an alcoholic returning to drink. As far as I am concerned, despite or perhaps because of my hunger for it, that piece is like poison.

For the truth is that I also love my daughter so much that anything sweet or tender reminds me of her. I don’t only mean a child on a street in strange city, wearing a dress of a style and colour I associate with my daughter, who can suddenly induce heartache, but even a bird calling in an overhead branch, ku-hu, ku-hu. I remember being in a small town in India a couple years after Ila had been born. In a dark front yard of a house where I had come to conduct a late-night interview, two young servants were busy with a black cow that was about to give birth. Lanterns swinging in their hands, the youths explained that the last time one of the cows had given birth, it had been in the middle of the night. No one was around to take care of the calf. In that crowded stall, the mother had accidentally trampled her newborn to death.

As I watched, fifteen minutes later, the calf arrived, its legs thin and crooked as in a child’s drawing. I could think only of Ila as I gazed at the lovely little animal in front of me: she was also the child whose drawings had given me a way to look at it that night. The creature’s arrival filled me with a sudden elation and it also made me miss my daughter terribly. It is the same when I’m in the train coming back from New York City, hoping to be home before she goes to bed. To participate in the ritual of preparing her for sleep, and then lying down next to her to read a story, offers me great joy. I will not exchange it for another hour of writing. At such moments, I have traded Raymond Carver for Wallace Stevens. When asked by Marianne Moore to turn in a piece on William Carlos Williams, Stevens said no, explaining in his letter: “There is a baby at home. All lights are out at nine. At present there are no poems, no reviews. I am sorry.”

Such grace. And, however impermanently, that sense of patience and grace is also mine. I say impermanently not only because, in my case, the feeling of sweet resignation that Stevens is describing gives way, sometimes, to the rage that Carver is articulating. That does happen, but what I have in mind is this: I put Ila to sleep and lie awake in the dark for a while; the lights are, indeed, out at nine, but not for long. I come out of the room and make my way slowly upstairs to sit down and write.

On occasion, I write about Ila. As I am doing right now. This is what writers do, they write about the world, and because their children often loom large in their world, they end up putting them into their stories too.

Carver certainly did. He wrote a poem to his daughter that invoked a similar effort by WB Yeats, except that instead of wanting his daughter to be plain, he wanted her to be sober. “You’re a beautiful drunk, daughter. /But you’re a drunk.” These are two lines that appear near the middle of what is certainly not among Carver’s better poems. In this poem, Papa is preaching against alcoholism. As in an aa meeting, there’s great value put on confessions of one’s own sins, the daughter being asked why she hasn’t learned from all the mistakes her parents made. No doubt because he’s a writer, Carver is better at description than he is at offering advice. The poem goes on to document the daughter’s degradation and her injuries at the hand of the man she loves. It’s all gritty and intense. Nevertheless, I wonder what Carver’s daughter herself thought of her father laying out in full public view the intimate picture of her sorry life.

I ask this as if I feel aggrieved; I’m not. I ask only as a member of the offending class. The offending class of writers. Once, when Ila was two, my wife was nursing her. Ila turned away from one breast to the other, saying, “This one not working.” I remember asking myself how long it would be before I used that in my writing.

When Ingmar Bergman died, many obituaries appeared in the papers; there was one by the British critic David Thomson that discussed Bergman’s isolation and his kids. “Probably no one knew the loneliness better,” wrote Thomson, “than the lovers, and the children, who saw how he put their smiles, their eyes, their meals, their untidy beds on the screen.” The phrase that stayed with me in Thomson’s obituary was a reference to Bergman’s “ruthless and obsessive use” of the smiles and faces of those he loved. Any feeling of guilt that I had was displaced by a curiosity about method: in what way was Bergman ruthless or obsessive? He had been married five times; he accepted paternity of as many as nine children. Did he meticulously portray the tangle of these relationships in his films? Most important, and this was a writer’s question and not a father’s, did he keep notes?

Ila would come back from pre-school and bring bits of her strange, alluring world to me. Everything she said I’d store like postcards from a fictional place. In my journal is a note that shows that when Ila was three she pored over a map and asked me, “Where’s California? California lives in the desert, right, Dad?” I thought that was precious but a part of me must have also believed that I could use that line in a novel. But even as I look at some of the other entries I have made in my journal, I see that there is another impulse also at work.

Consider the line that Ila offered at bedtime on 18 April 2007, when she was a few months short of four: “I know only two things. That I have to wear loose clothes when I go to sleep, and that we have to be nice to each other.” These are not notes for a novel: instead, these are memos to self. “Shape up”, these memos say. There are several entries in this vein in my journal. I find myself reflecting, not only on my daughter’s sweetness, but also on my secret desire to be the person that my daughter thinks I am. This becomes clearer to me when I read in another entry that after a ten-hour journey, when Ila and I are picked up late at the train station by her mother and I complain about the time we have spent waiting in the cold, Ila silences the apologies by saying, “You were on time, Mom. You were on time.”

My daughter thinks I am the person who will take her to Disney World. Who am I to pretend to be otherwise? This was a couple of years ago. My wife, who is an economist, refused to come with us. She said something like “It is a corrupt consumerist trap, you cannot possibly take Ila there.” I enjoyed the trip very much. I confess I had mixed motives for visiting Florida. In the pages of The New York Times, Thomas Friedman had written that post-9/11 America had become hostile to visitors and our government was exporting fear, not hope; more specifically, Friedman had complained, “If Disney World can remain an open, welcoming place, with increased but invisible security, why can’t America?” Friedman’s remark sparked my curiosity. I suddenly felt that I could excuse my extravagance.

Once there, I noticed that bags were searched before entry but there wasn’t much more that I could observe. This becoming a research trip was unlikely. It wasn’t as if while rushing from the Caribbean Beach Resort to the Magic Kingdom, I could touch Mickey Mouse’s elbow and ask, “Say, where are the hidden cameras?” Not only that. Even if I had found the answer to that question, perhaps all I’d have wanted to find next was whether the cameras would reveal where the lines for the rides were shorter.

Frankly, I couldn’t have been happier than doing what I had really come to do. From morning to night, nervous about a thousand things, I took my child in a rented stroller from one overpriced event to another. There was tea with Sleeping Beauty. There were endless encounters with people in cute, but no doubt hellishly hot, stuffed-animal costumes. We met patient princesses who held their smiles while parents of the kids standing next to them figured out how to use a simple digital camera. I was anxious that in the heat my daughter looked sunburned and thirsty. But I was happy not to have to think about work. I was on holiday with my happy child.

It is not always like this. I can be in another city for work, perhaps on way to an interview, but I’ll be searching with one eye for a toy shop. There was a period of time when I would take the train to New York City to attend a terrorism trial — but even while rushing to catch the subway, I’d stop at a kids’ store in Grand Central station to buy a little gift for Ila. I was often late to court, and when I took a seat on a bench near the door, a witness would already be halfway into a story about illegal funds. I would hear about where the money went, but have no idea about where the money came from!

Such happenings leave me conflicted. Not about the plain fate of being a father — although one evening, when she was four, Ila looked up from a game she was playing with me and asked, “Are you tired of having a child?” — but about how I deal with my responsibilities. Last October, I was in Beijing searching for clues to two writers’ lives early in the twentieth century. I went to museums and libraries, and even to cemeteries, but required more information for what I wanted to write. A lot of work needed to be done. Instead of pounding the pavements in search of people who would provide me what I needed, I found myself one morning in Beijing’s Hongqiao Market looking for a Chinese costume for Ila. Her instructions had been precise. She had watched Mulan on TV, and wanted what Mulan was wearing. Earlier, I had stopped at a store called Cinderella but it only sold bridal dresses; Hongqiao Market didn’t disappoint, it was full of goods that we think of as stereotypically Chinese. The shops were packed with haggling Americans, and salesgirls who, in a show of intimacy, would each grab my arm and shriek, “Very cheap, very cheap.” I had a list of things I needed to buy, which included a Chinese doll and a paper kite; on the back was the outline of two little soles because, as you might be aware, Mulan also wore distinctly Chinese shoes. I had to search for these items with care but what was also exhausting was the pressure to bargain. For thirty yuan, one could buy a pot of green tea, and, more than once, I sat down to sip tea and collect my wits. And during those breaks, I asked myself whether I shouldn’t have actually been conducting interviews at the Beijing Normal University. The answer was perhaps yes, but what was undeniable was the elation I felt as I ticked off what I had purchased on the list. It was my best day in China.

In January 2004, a Seattle paper reported that a conference was going to be held in Yakima, Carver’s hometown, to honour the writer’s memory. The keynote speaker was Vance Carver, the writer’s forty-five-year-old son. The younger Carver had declared his intention to remove the misconceptions about his father’s early family life, about the bad years before the writer sobered up and did the work that earned him his name. The younger Carver had told the newspaper: “His years as a family man before 1978 are often depicted as dark years, as a baleful time that were hard on him, that somehow have no redeeming value. That’s only part of the story.”

The detail that caught my eye in that news item was Vance Carver’s mention of a famous story of his father’s called The Compartment. This was the first story of Carver’s that I had read. A middle-aged man named Myers is on a train, going to visit his son whom he hasn’t seen for eight years. Myers thinks his break-up with boy’s mother was because of the boy’s own “malign interference in their personal affairs”. At one point, Myers steps back into the compartment after a few minutes’ absence, and finds that someone, possibly a fellow-passenger pretending to be asleep, has stolen the expensive wristwatch he had bought for his son. The mood has soured, and Myers realises he never wanted to meet the boy or make small talk to him. As it happens, more and more things go wrong, as they inevitably will in Carver’s fiction, and it becomes clear that Myers isn’t going to see his son anyway.

In the news story, Vance Carver had pointed out that The Compartment was based on a trip that he had taken to Paris with his father. But that wasn’t all. He also said that his father had transformed what had been a pleasant memory into a dark tale of a troubled relationship between a parent and his progeny. And yet, he said that he had liked the story but simply wanted people to know his relationship with his father didn’t resemble what we encounter in the story. Such pathos, such poignance! It is not only parents who have fantasies about their children. The opposite is also true.

But that is beside the point. I don’t myself know what I want to believe more. That the lives of the Carver children weren’t always as miserable as their father’s writings had suggested, or so clear and steadfast was Carver’s vision of reality that his imagination turned all he touched to something squalid. Here, I have a private fantasy of my own, which is a writer’s fantasy, fatuous and self-serving, and it goes something like this: Carver was good at hiding the drunkenness and his frustration from his kids when they were growing up, but when he sat down to write he hid nothing and tried his best to cut close to the bone. Of course, a writer’s greatest fantasy is that he or she will keep writing well. When Carver was doing that, a few years before he died of cancer, he claimed in an interview that he had regained his children.

At the end, Carver seemed to have found a balance in his life. I haven’t found that place yet. Perhaps because I haven’t felt myself at the end of my tether, or not for too long, I haven’t also scripted for my life bleak little narratives of destruction. But I think of Carver often. One night we were sleeping at a friend’s house. I woke up Ila at night and asked her to come to the bathroom with me so that she could pee. But she refused. I was afraid she was going to wet the bed. I tried again and again, and lost my temper when she crossed her arms and angrily turned away her face to the wall. I put off the light and said I wasn’t going to lie down with her anymore; she could sleep by herself. Ila began to cry then, and when I put on the light a few moments later, she was standing on the floor. Her hands were stretched out in the dark; her eyes were still shut, and tears were streaming down her cheeks. Such shame. The squalor of love, the play of power. That is probably what made me think of Carver, although in him one would find no quick redemption through swift kisses. There is little search for forgiveness in his writing, only the clear putting down of the right words for all the wrong things in life. He came to mind the other day again when I found myself thinking that there is a word in the English language for loving one’s wife too much, but none for lavishing too much affection on one’s daughter.

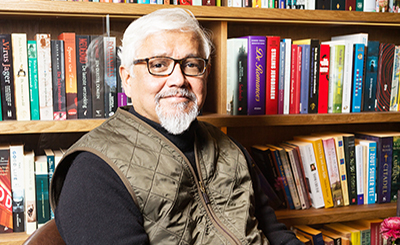

(Excerpted from Lunch with a Bigot: Essays by Amitava Kumar, with permission from Pan Macmillan India)

THUMBS.jpg)