The Caged Bird Rehearses Before It Sings

Papa’s antique Sony radio preaches the vacancy around it;

the harsh sound of a religious scholar

dampening the sonorous call for Fajr prayers.

There are so many ways to declare the break of dawn.

Morning breaths create nebulae over our heads,

Weightless water from sprinklers haunts the fern of its longevity.

There is always the phlegm-filled clearing of throat

around shuttered tuck shops; an aubade for the sparrows

who have forsaken their shepherd-like voice

because the ritual of morning songs has long been

replaced with Israfil’s trumpet rehearsals.

The stomach churns like the shriek of a kettle;

an alarm to remind our bodies

they are only ours until hunger strikes.

This frequent need to be fed is an heirloom from the maker;

the one who lost himself in the music of his creation.

Papa takes control over the faucet in his hands,

the water drizzles until it’s warm, until the skin can bear the heat;

as if this too is a test for endurance.

Bags zip and cars fail to orgasm in their masters’ grasp.

We have created so many objects to validate our sentiments.

The cold summer breeze creating welts in our chests,

that one leg hugging the pillow, struggling to let go.

One of us has to run to the kitchen to prevent the chai from

spilling over the stove. Every morning is a cold stab

of mint on our sore gums. That’s how the world is restored:

with a cold stab where it hurts the longest.

Portrait of a Photographer as a Historian

Travel back to a still shot, it has an earthly existence;

babbling blobs of spellbound hibiscus and thistles.

The photographer is not naïve; she scours every

starlit vision before snapping it between her fingers,

between the whorls of breath. She has always known

Nature to be fraught with unexplored terrains and levees

and footnotes to past lives. The rustling of every lost

artifact, the cold hush of a Harappan language.

How rusted is history, to be called a rustic beauty?

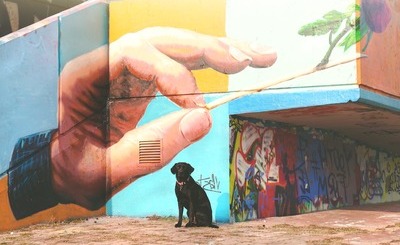

All that is gone is an improbable threat, like a muted mural.

The photographer is caught between erasure and exposure.

A great old oceanic sound erupts in heruvula:

who is Frankenstein, the panoramic landscape or its

motionless silhouette?

The lifespan of a shot is akin

to a gash that has already bled. Every creation is a musical

dribble on the windshield, wiped away when conceived;

artistically willed into depletion. The key is to take as many

still shots, to taste the rum on the photographer’s tongue,

to call god ancient and benign. Answers hanging like weary

autumnal boughs. A man-made object is dead is redolent

of a microcosmic uncanny. There is nothing to unearth

from wreckage. All history-makers, photographers, artists

and dancers have one memory in common: they danced

around campfires to perish in the lucid after-echo of cymbals.

Outro to Grief

Boredom is a legacy. You crave cigarettes,

if not cigarettes then a Siamese kitten;

Blueberry, his malleable purrs, if not a kitten

then your own life hung in the billows of lampshades,

this jarring sorrow coiling around you,

like Madhubala’s regal twirls in those thousand

ceiling mirrors, the melody of moonlight.

How boringly slow a funeral procession is,

intensive too like the seven minutes Nana Abu lived

before dropping his arm on the spring mattress;

a whispering thud evacuating the last drop

of exultation. A myna with her Tuscan-sun beak

leaves the clay pot aquiver on the windowsill.

There comes a time in the longest day, you get

bored of mourning so you liberate yourself in

a small room, puff a Parliament, think of ways you

could destroy the last horcrux — that has kept

the day alive — to hungrily let go of this humdrum.

Kill the Refugee

When you see a newborn refugee,

first let your eyes peer through metal

barricades, the sky a glaring tangerine

blending in the seams of malnourished

cityscapes. You may have never seen with

your bare eyes the ululations of a family

forced to abandon its grave; the soil

of the homeland is a native’s great beyond.

Imagine not being able to die at the time

of your death, someone has to dodge

Azrael’s all four faces to stay on Earth,

become a landfill of memorabilia,

a creature of yore. Look, a different kind

of man lived here, reduced to a different

kind of rubble. Look, the ruins don’t

speak the language of home. Of homeliness.

It happens sooner than later, underneath

the scintillating Canopus, your grandma’s

cutlery submits to the staccato of

someone else’s kitchen-table jargon.

The objects are diagnosed with amnesia.

That bisque ceramic teapot and the abluted

prayer rug, and the dog-eared calendar,

and your father’s unused musket sagging by

the wall; now face a brand new qiblah.

Perhaps, even god had to remember what

he is made of, what he left behind

before pronouncing himself omniscient.

It only takes a billion years to chant

the names of your belongings before

losing them to this news, say, on a radio

in a burgundy Alto; which then seems

like the only place where homesickness

is not a deliberate crime. Remembrance

is exorcism.You don’t know which

demon of geography you will summon

when you saunter inside a bereft thought.

You have to ask yourself,

are we allowed to mourn?

The next time you go to a playground

and you see a newborn refugee;

weary shadow of an Afghan boy kicking

plastic bottles on the dirt of Rawalpindi,

his shalwar flapping; one brisk kick at a time

in the dark of daylight: you should muster up

the courage to kill the refugee, the Afghan,

the boy, the threat. Then call him a child,

your very own. Return him the tears, his tears.

Ode to a Nurse

The pretty nurse taps her feet,

nibbles the fuchsia colour off her nails,

rests all day in the plastic chair,

cares for her patients’ bodies till they bloom

into sedimentary macrocosms.

She interlocks her death-licking fingers,

remembering the fragrance of Shea butter

she stole from a surgeon friend’s purse.

Her phone tings,

she whispers texts to her lover,

except the texts do not confess love

in the Bollywood style,

she reminds the time around her

of the rhythm of unreleased pleasure

squirting in her nerves.

Between these lonesome intervals,

Karachi whizzes through her reveries,

sometimes a train foregoes a lunar death,

onion peels chant a mystic spell

in the far offing of ill-grown greenery,

husbands quarrel in tall buildings.

Her hindsight can never forget

the distinct sounds of these husbands.

She stares into the effervescent gloaming

of her patients’ eyes, knows

which one needs to recite the kalima.

Her mouth chews on cashews

and peanuts, like its cud.

How cunningly she has earned

the title of a prophet,

sensing the advent of Qiyamah

when a patient gives up his snores.

She knows that lungs hold more

than a thread of breath,

and that death too

demands careful nursing.

Wedding Mashup

The beat of Punjabi drum, a very masculine bhangra

and the groaning aunties measuring gold and diamonds

with their tongues. A perfect proletarian wedding

with bleats of glitter and palpitating gossips, masala

and all that sugary tarnish of cordial mimicry.

I want to be the most uncalled for blackout;

dark then limned, a cigar I am keen to light up

in the rose bed of aunties and uncles praising

someone’s girl for being a doctor who can cook.

Long wisps of smoke respiring through my unchaste

lips, and I am so tired of sitting with my legs crossed,

my ghagra flirting with my stiletto heels,

I am so tired of smiling without a grin. The food

isn’t served yet. I smell steaks and the subtle singe

of barbeque, the chilman biryani hiding behind

her inability to express. I am tired of uncles calling me

their pretty daughter only to burn their voyeur eyes

on my nipples concealed under my silk diamantes dupatta.

‘Don’t slouch’, says an aunty. She runs her fingers though

my hair, measuring the length and the femininity conditioned

in the fine purple streaks. Purple is not a graceful colour,

maybe a tinge of blonde or brunette to give the men

a western dream: untouched and impossible to possess.

I am beautiful, beautiful in the way I want to spread

my legs across the table, where Pepsi is served in wine flutes,

and men rape their wives with their eyes and the wives

of their friends. These heels are killing me and the clothes

and the barriers and the uncles and fathers and aunties

and no one cares about the delicately arranged love

between the couple. I yawn, like a gypsy fox that is ready

to trot home, without spreading her legs, without

lighting a cigar, without telling the uncle that my nipples

are supple skins trapped inside a lavender brazier;

trust me it’s not an invitation concealed in a metaphor.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated