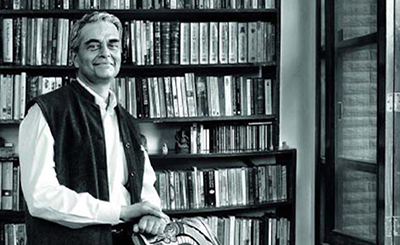

Unni R. Photo courtesy of the author

Noted Malayalam writer Unni R’s short story collection underlines his mastery of storytelling

He sits in his usual corner of his favourite cafe on the Kowdiar-Kuravankonam street, which is dotted by some of the best cafes in Thiruvananthapuram. Unni R loves his coffee and the ambience of cafes, a far cry from the rural milieu his stories conjure up. The mid-morning light pools in his deep-set eyes. His beard is freshly trimmed. His cap fits perfect.

Unni sips his coffee, and looks out to the street. He won’t find any of his characters walking by. They all are far away in his village of Kudamaloor in the central district of Kottayam. The passing cars catch the sun and reflect like lightning before they fleet across the window.

“Yes, I am apprehensive,” he says, “as a writer of a time when writers are shot dead or silenced.” Unni, one of the leading voices in Malayalam literature, believes, despite the darkness that envelops us, in the moral duty of a writer, and that of literature. “You just write,” he says, taking another sip from the coffee.

“Writers may not be able to bring out an immediate reversal of what is happening in India at the moment but literature is a powerful tool which in the long run will bring about changes,” he says.

Unni’s first collection of short stories to come out in English, One Hell of a Lover (Westland), wonderfully translated by academic J Devika, has pitchforked him to the national attention and showcases for the readers beyond the confines of Malayalam one of the country’s contemporary and powerful storytellers who picks up the sylvan lives he has seen around him and weaves a world of universal appeal and relevance. Unni’s stories are a reflection of the rural life, with its menagerie of characters caught in a vortex of simple to complex character traits and behavioural patterns.

Unni’s eyes are both piercing and transcending. They pierce through the socio-cultural layers, which are obvious, with surgical precision, and exposes the complex and secret lives, passions and fetishes of mundane, earthly lives. Unni leaves the highways of urban life and takes the less-taken roads of rural interiors in search of stories among rubber plantations, cassava and yam orchards. “It is in the inner lanes and less journeyed village pathways of pastoral tracks with hedges and streams that I find my stories.”

Unni’s eyes also transcend the cultural borders, and they seek and find the merging point of the rural and universal. His stories essay the lives of both farmers, shopkeepers, wayfarers, homosexuals, voyeurs and literary luminaries with equal panache. Unni’s stories are noted for their craft. “Each story has its language or diction demanded by the story itself,” he says. “Each story is a journey…not a well-planned one…it takes on and leads me in its own trajectory.”

Unni, who is also well-known for his award-winning movie scripts, believes unlike his writing for cinema, his stories are not written for masses. “Some stories don’t go down well with the general readers.” Unni is also aware of the fact that in Kerala there is no dearth of pseudo-intellectuals who pounce on everything written with a hint of world literature. Some of Unni’s stories are based on stories of Hemingway, and he knows only few readers could really understand the inner layers of such stories as “Water”. Unni’s stories often break the conservative. However, Unni believes that Malayalam literature is of global standard. “Some of our writers are at par with masters in any language.”

Unni’s diction, though simple at the outset, is layered. He has the uncanny skill for turn of phrases and conjuring up a magic world by making the abstract tangible and living. Unni’s world is also of magical realism. Once Salman Rushdie said of magical realism in a memorial lecture on Marquez that the problem with magical realism was that we only hear the word “magical” and tend to miss the equally important part of “realism”. To an extent, it is the other way around in Unni’s diction. We tend to see only the “realism” and we often miss the “magical” part of his prose. Unni is a master storyteller whose characters are so real and everyday that we often don’t get to notice the fabulous or fantastic part of the narrative. He takes the world and earthy characters from Kudamaloor, and in a masterly wave of his wand, turns them into ethereal beings — transporting the readers from the realms of reality to the stratosphere of the imagined or the magical.

J Devika, a well-known feminist writer and translator, has done an exemplary job of translating Unni without losing the nuances of his layered prose. She has, in a way, got under the skin of Unni’s diction and narrative. Unni duly calls Devika’s contribution as “trans-creation”. “The translation is equally good,” he says. One Hell of a Lover has been shortlisted for Atta Galatta Bangalore Literature Festival Book Prize.

Another latte arrives as Unni obliges a college girl’s request for a photograph with her.

Unni is political, and so are his stories. Unni’s politics has been conditioned by his student days and extensive reading. But his politics is not in-your-face type. That’s where Unni’s craft comes into play. He places them cleverly in his stories like a slow-burner, making the reader think it over. In a politically hyperactive state like Kerala, a writer like Unni cannot shy away from reflecting on the socio-political realities.

“Caste is a reality,” says Unni. “I don’t think that as a writer I can be politically correct by naming or making my characters look bland, apolitical or neutral.” In Kerala, it has been a practice to address people by their caste. “It’s been there for years, and my characters are often called by their caste irrespective of what they do,” Unni adds.

Unni fears that Kerala will soon be fragmented by religious bigotry and communal hatred. “That’s why I am apprehensive as a writer.”

Unni’s only novel, and his latest work, The Rooster is the Culprit, which will be published by Westland, translated by Devika, is a telling tale about the "unknown fear" that is being driven into all of us in the contemporary India. A simple yet disturbing story of subtly telling us how we all are changing, it also shows Orwellian traits of political satire and prophecy.

Unni finishes his coffee, and smiles. In his eyes reflects the noon sun’s fierce light.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

I loved the way the narrator gives an anatomy of the person sitting before him. That's quite unusual to my experience. (and yeah, now you cannot portray Unni R without that salt and pepper beard and legendary cap. They have become the landmarks.) This anatomy is not limited to the body or coffee but to the vision. And yeah, about Magical realism, it's true that when the work is being written, the author is writing the realism, he is narrating a story as he sees it, it is only a reader, who is not from the cultural context of the writer finds magical elements in it. I remember myself reading One Hundred... in my teenage days and as someone who hasn't crossed Western Ghatts more than once, I couldn't find Magical elements in it. But, few months back, when I read the novel as part of my course, I was wondering why I didn't come across these elements earlier. Then I realized, two years in Delhi and a break from a "superstitious" world made the difference.

Badshah Ibrahim

Dec 2, 2019 at 13:32