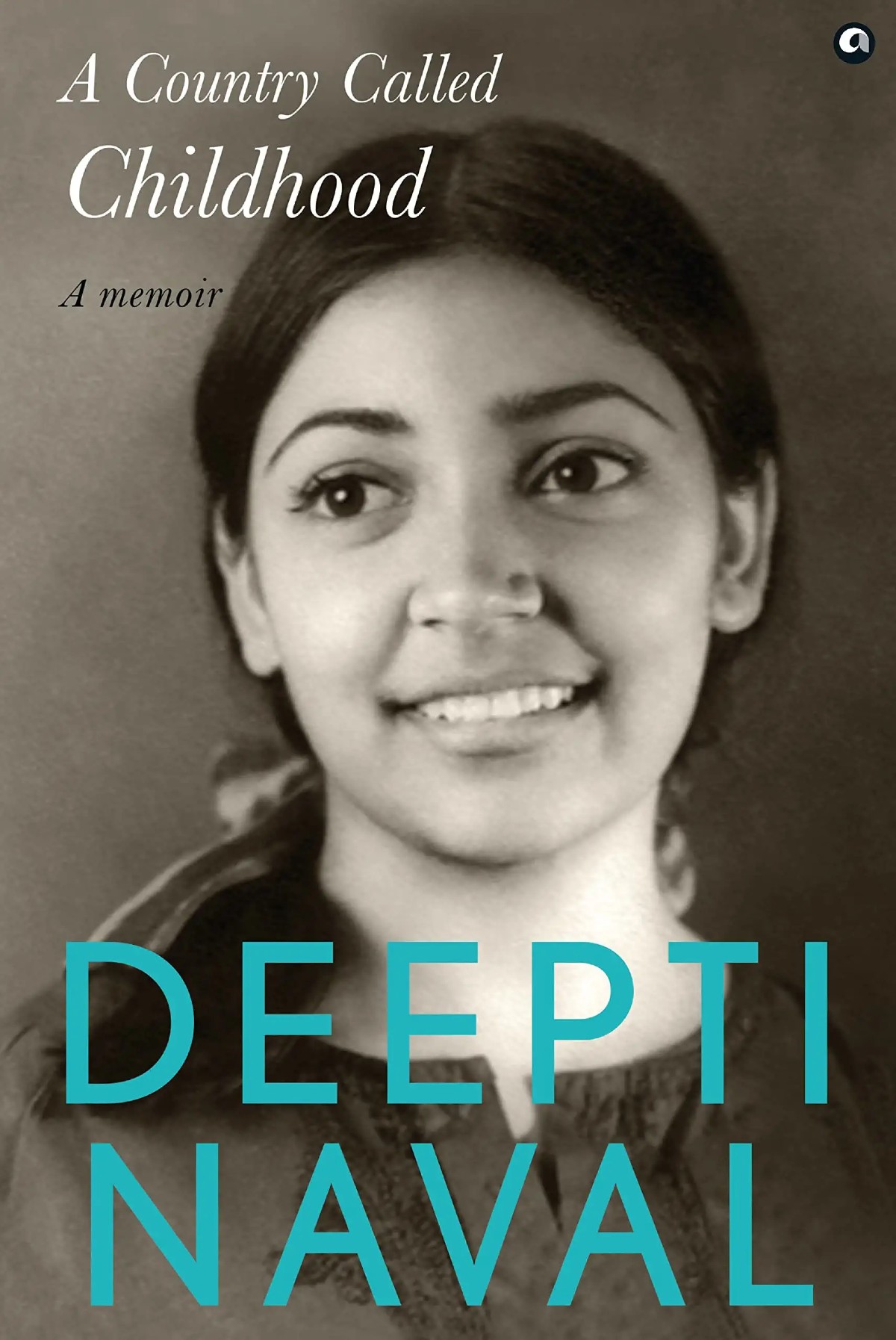

Deepti Naval. Photo courtesy of her Facebook page

Partition played a role in Deepti Naval’s family life — her parents met in Lahore and somehow managed to cross the border — though the small village to which Naval’s Piti (as she called her father) belonged was wiped out in an act of mindless genocide

Families with large houses are similar in many ways. Stories of the rooms and the people who lived in them, the surroundings and the way life is lived day after day through a series of scenarios, overlap. In her memoir, A Country Called Childhood (Aleph Book Company),Deepti Naval is very clear that she is not laying out a linear narrative. Instead, she wants to present her growing-up years like a film with the scenes that made the most impression on her in a collage. This is why the prologue opens with the drama of an afternoon dust storm in Amritsar sweeping out of the sky with the little Deepti rushing through the dust whirls in search of her Mama who has gone to the cinema. Ultimately, the child is rescued by Sardi Mai, her ayah. From that dramatic beginning, the memoir unfurls travelling through the country she calls childhood.

Naval has her scenarios neatly laid out, setting the background of her Chandrawali house and the neighbourhood in which it lies, hard by the Khairuddin Masjid, with the mochis in the galli below, an area she calls Mochistan. Floor by floor, she tells the story of the house and its inhabitation in the walled city. The first narratives are confined to her and her sister and their relationship with the maids, the neighbours and the children and animals — mainly the cows around them. The story begins to open up when she talks about her parents’ families and their very different origins. Naval’s mother, for example, grew up in Burma, had a passion for Bengali women and their songs and loved the city of Lashio, a love that she never outgrew. Naval’s Piti or Pitaji was a failed businessman who ultimately became a professor of English literature with great reluctance.

Naval describes the great escape from Burma with her grandmother insisting on carrying a gramophone on her back tied in a kind of sari sling and talks about the resultant loss of place time and time again which made her mother’s father see himself as an eternal refugee who carried the sadness of forgotten dreams in his eyes.

A Country Called Childhood: A Memoir

Deepti Naval

Aleph Book Company

pp.388, Rs 999

The story is one of different types of bonding and the varied equations that come to play in family life. These are illustrated by anecdotes, some told in the words of those to whom the narratives belong, the rest in Naval’s simple, lucid style. Those with convent upbringings will relate to the experiences with nuns and uniforms which cut across state divisions. Partition played a role in her family life — her parents met in Lahore and somehow managed to cross the border — though the small village to which Naval’s Piti (as she called her father) belonged was wiped out in an act of mindless genocide. Different kinds of tragedy stalked the different wings of the family whether it was through life and death or through career choices.

Naval brings in lyricism through her family trips to Kullu surrounded by mountains and apple orchards and the train rides that were part of the great Indian family life. She shares her world of picnics, treks and food with the reader or opens up family celebrations with candour and amusement. Her mother was fond of dresses and liked looking for new styles for her daughters from the then easily available Woman and Home. Gradually Naval starts opening up her world and introducing her growing interest in acting — which started when she was a child following her Didi’s orders. She writes about her encounter with Balraj Sahni and her determination to follow his humility under all circumstances. She also points out that her Mama, who acted in charity shows, faded out from theatricals in silence because it did not find favour with the conservative women whom Naval’s grandmother knew — something that Naval writes she would never have been able to do.

Ultimately, Naval writes a coming-of-age story that is a love letter to her mother — she unabashedly calls herself a mummy’s girl. Their bond was one of artistic traditions shared with a focus on film. Notably, the painting of the Amritsar mosque on the back cover of the book — the one that was a stone’s throw away from their house — is by her mother, who passed away in 2017 and who had gradually separated from Naval’s father, revealing the crack in what, to the children, had seemed a perfect relationship.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated