As much as it is a book about memories, it is also a book about the nature of language and the limitation of words to convey that which had plagued the darkest corners of a troubled mind

“Deepak becomes Virgina Woolf. A wolf who is always advancing into the depths of the sea. And the sea frees it. How shallow is my sea. It reaches only my knees,” Swadesh Deepak writes of himself in his searingly honest and audacious memoir, I Have Not Seen Mandu. Originally published in 2003 as Maine Mandu Nahi Dekha and translated into English by Jerry Pinto, the author of Em and the Big Hoom, it recounts his excruciating struggle with mental illness for seven years in a rather non-linear, fragmented fashion. He quotes from Lady Lazarus and identifies with Sylvia Plath, he invokes Shakespeare from Hamlet, is visited by the characters from his plays and meets people, real and imaginary, who informed “Sabse Udaas Kavita”, the play he writes after recovery. And yet for these tormenting years he found himself without words, the ultimate hell for a writer, as Pinto puts it.

A professor of English and an eminent Hindi writer, renowned for his hugely successful play, Court Martial, which has been adapted to the stage by mavericks across the country, Swadesh Deepak fell into the throes of mental illness when, as he reiterates multiple times, a woman expressed the wish to go see Mandu with him but he refused and abused her, ferociously. This woman, whose fatal beauty he compares to Helen of Troy and Draupadi, visits him at night, sometimes with three white leopards who serve as her bodyguards, invites him to Sundarbans, and at other times promises to take him abroad. Deepak calls her Mayavani, the seductress. But this woman, who has drowned him into the sea of sorrow, has made him forget his language, taken his pen away from him and castrated him, made him Mahabharata’s Brihannala from who was once a raging Arjuna, is a secret he carefully and stubbornly guards, from his wife, friends and doctors but ultimately relents on his way to recovery.

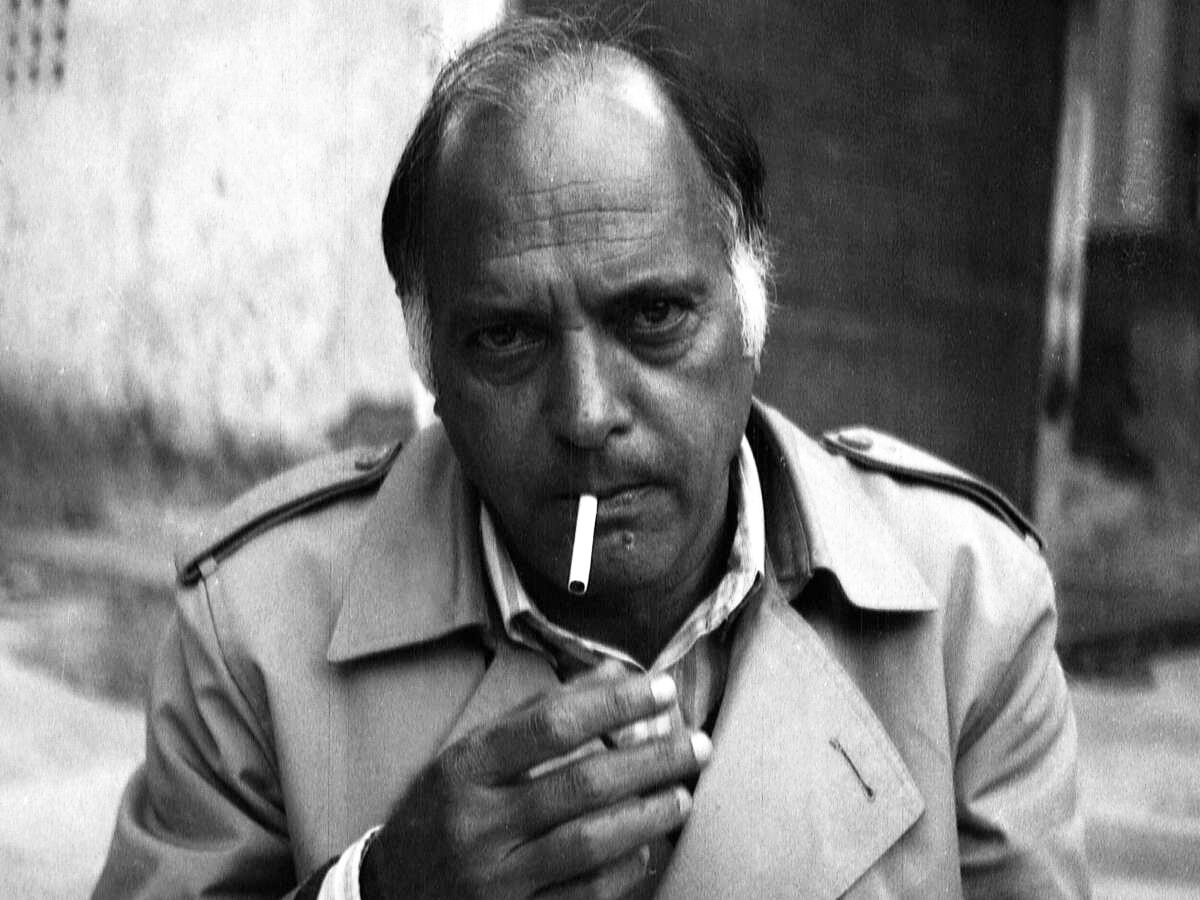

Swadesh Deepak. Photo: Soumitra Mohan

“What I could not remember accurately, I salvaged by talking to my family and the people at the hospital. My armoury began to fill again. I thought memories dry out in the sun; I was wrong. Memory lives in the soul and therefore it is immortal.” As much as it is a book about memories, it is also a book about the nature of language and the limitation of words to convey that which had plagued the darkest corners of a troubled mind. When a writer finds himself at a loss for words, is it the failing of the mental illness solely or language itself? And when a person reads it, wishing for more context, perhaps a little more order, maybe just some indication of differentiation between the real from the delusional, is it a failing of the individual reader or the way we have conditioned ourselves into reading ‘the normal’? Perhaps if the sentences did not melt into each other and the time periods did not become fluid as they do, leaving us gasping for breath, welling with questions and searching wildly for meaning, we might have had gotten an emotional sense of the dark pit Swadesh Deepak found himself in and yet would have had not an iota of idea of its bottomlessness.

Swadesh Deepak recounts the hilarious story he told Faiz Ahmed Faiz about how he learnt Urdu because his mother would ask him to get his father’s love letters to his mistress translated. Beyond the complexities of understanding and empathising, this book is also about the peculiar and fated ways we learn languages and remember words, dive nose deep into the world of literature and let its magic take hold over us and sometimes, haunt us. In the very first chapter, we find ourselves placed in a room reverberating with the intellectual repartee and satirical banter among the stalwarts of contemporary Hindi literature, a recovered Swadesh Deepak one among them. The great Krishna Sobti always clad in black, Soumitra Mohan who doesn’t shy away from calling even his own work ‘raddi’, formidable Sheila Sandhu whom he calls Jarnail and Nirmal Verma who he says is “a secret service agent of the soul” are figures we then meet on and off both in his mental space clouded with hallucinations and blotchy remembrance as well as when he writes about the past and the future. While in hospital, he remembers having the vision of Yeats being seated in front of him, pushing white hair back from his face and putting on a pair of golden spectacles, saying “I made friends with your poet Nirala in Heaven. He gets very angry if one does not memorise one’s lessons. But he is interesting. Next time, I will be reborn here. And write poems in Hindi.” Maybe Yeats’ desire to write in Hindi in this dream was the projection of his own longing to befriend his language again at a time when he would quote Plath, Shakespeare and Eliot relentlessly, addicted to speaking of English which he calls the language of lies.

I Have Not Seen Mandu: A Fractured Soul-Memoir

By Swadesh Deepak, Translated by Jerry Pinto

Speaking Tiger Books,

pp. 360, Rs 499

In Em and The Big Hoom, a heartbreaking portrait of a family sticking together, at the centre of which is a mother reeling with mental illness, rendered in marvellous dialogues, Jerry Pinto writes, “Love is never enough. Madness is enough. It is complete, sufficient unto itself.” The frustration, the helplessness, the love, the embarrassment, the motley of emotions, raging and mute, which the friends and family, the caregivers of a mentally ill person harbour and battle, encapsulated in these lines, ring true for Swadesh Deepak and his family too. “It is a mystery why family members and friends are always sure the mentally ill person is lying. Nothing is actually wrong with him. He is lying on the bed only to evoke sympathy. Often Geeta, tired and angry, would say-Nothing is the matter with you. You are shamming. You don’t want to work”, he writes. The stoic Geeta, his wife, stood by his side unwaveringly throughout, longing for her “lion hearted” husband, caring for him tenderly and snapping at him harshly, “If you really want to die, why did you sell the .22 rifle? The sea liberated Woolf? Well, Geeta will liberate you…..Your son has started telling his school friends that you’re not his father, you’re his relative”. His son, Sukant Deepak, gets his own chapter in A Book of Light, edited by Pinto himself, which begins with the image of a boy lying on his bed, trying to sleep with an iron rod underneath it. His father who is outside the door, knocking, has recently returned from hospital. He loves his father; his father loves him. The rod is ‘just in case’.

“Forget about time and the sequence of events. Liberate yourself from past-present-future. Write it down as it comes back. Genre, style, forget about these things. If you want, write a poem” put in dialogue as if it’s a play- a fractured prose for a fractured autobiography. And then we will have the first book that is like us.” Had poet and editor Giridhar Rathi not reassured Swadesh Deepak, this book might never have been born since he was insistent that he didn’t want to write about his mental illness, that “it’s tough, very tough” and that “he didn’t remember the events in any order”. When he went to meet Ebrahim Alkazi, the doyen of Indian theatre, Alkazi had said to him that Shakespeare’s King Lear was a tragedy of a king but Deepak’s Jalta Hua Rath was the tragedy of a country, as great as the former. Swadesh Deepak writes, “I always write the last scene first so that I will never stray out of the frame I have set myself.” At the outset we have been told that we do not await a happy ending, that one day he left for a morning walk and never returned. Perhaps I Have Not Seen Mandu is also a tragedy, not of a king or a country, maybe not as great as these canonical texts, but that of a mind descending into madness to recover only briefly and then to surrender itself to a darkness we won’t ever know, a tragedy without an ending. Only Swadesh Deepak would know the kind of ending he gets. Maybe Yeats still imparts him words of wisdom about the nature of a seductress, about his love for Maud Gonne. Maybe he still hunts his characters with a loaded gun.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated