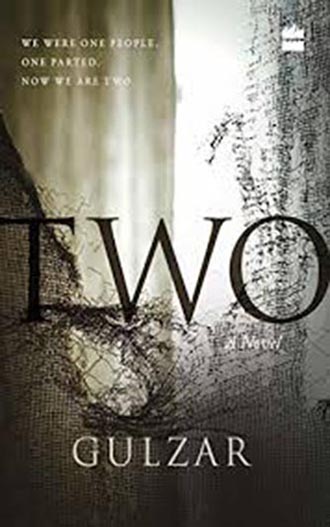

Gulzar’s first novel Two is not just his search for a catharsis from the Partition and its wounds; it is a bell sounding out the possibility of other Partitions that could be brewing in the darkness of human minds

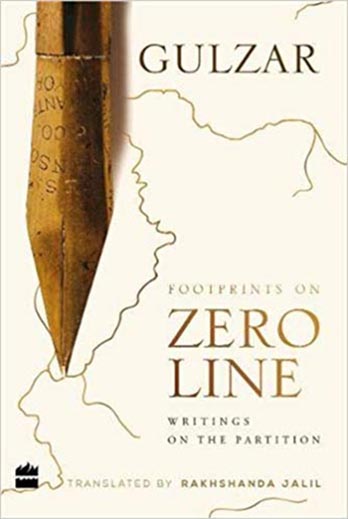

Footprints on Zero Line: Writings on the Partition by Gulzar,

Translated by Rakhshanda Jalil,

HarperCollins

pp. 206, Rs 399

Two: A novel by Gulzar

Translated by the author

pp 179, Rs 399

Poems, essays, short stories... The fact that the Partition has been haunting Gulzar through the years has reflected in his writings, sporadically. Footprints on Zero Line collects all the angst in its pages.

Most of the content disturbs, pulling at the readers’ comfort, uncovering a disquiet that every violent upheaval has evoked in them and which they have sought to push beneath the many layers of daily living. The poems are particularly poignant. Some recreate images from the poet's childhood, in others we walk with him as he visits his childhood haunts in Dina, across the border, where 'it has taken me seventy years to return'. He shares his dreams of mustard fields, and ' the house where I was born/ where all day long the sunlight /Pouring through the iron grille on the roof/Transformed my courtyard into a chessboard.' And carries the reader along as he flies on wheels, 'Pointing out wondrous sights over the Jhelum/ Where boys float over the river on watermelons'...

Other images are less magical. In “Bullet”, Gulzar describes the violence of a gun wound with cinematic precision:

'The bullet wove its way through the turban

And the blood splattered on the wall

as though someone had spat a mouthful of paan...'

Then the poem turns as only Gulzar can turn it, from violence to a personification of sorrow as he writes:

'A stunned silence stood for a while

Someone could be heard whimpering

Standing quietly in one corner of the house

An oil-lamp kept quivering.'

The poems are also in the original, printed alongside the translations. And in every turn of phrase in the originals, there is the inimitable voice of a poet who can make us laugh, cry and as here, gasp at the power of his emotional link with his roots and the angst over being torn away from where part of him still belongs.

Many of the stories in Footprints on Zero Line have appeared in other collections. “Ravi Paar”, from a collection of that name, is one of the most powerful Partition stories I have read, and it finds a place here. Two soldiers bring out the irony inherent in the fact that men who are children of the same soil have to fight on opposite sides of an imaginary line. Each story holds a different reflection of the author's experience, which he bedecks with imagination and sets into evocative prose.

A dialogue between the author and Joginder Paul on their fiction and Partition is the last offering in the book; not counting the translator’s note.

It is not easy to read this book in one sitting. The feeling of helplessness, of being a pawn in a game played by blind men that Gulzar conveys is overwhelming. Yet, it is a vital book, from a voice that has over the years been best heard conveying the emotions of celluloid protagonists but now speaks out both as history and a prophet of what the future can still hold, if the wounds the past inflicted pass out of memory.

Two is Gulzar’s first novel. It is a small book, and though it reads well, I am sure the original packs in even more power in the turn of phrase and vividness of description.

Unlike Bhisham Sahni's Tamas or Khushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan, Two does not explode. It smoulders. The unease, the fear and the feeling of creeping terrors that are as yet beyond the imagination are sparks that lie hidden under the slowly emerging tale. The characters, many based on real people, reveal themselves slowly; ordinary men and women, living together, sharing lives, each with his loves and hates but welded by a common space. The rifts are revealed not with the suddenness of an earthquake cracking open the earth, but with the menace of a tsunami gathering itself quietly in the far distance, gaining strength with every wave, till the ocean can contain it no longer and it rises, serpent like, above the surface and moves swiftly but quietly inland, to destroy everything in its path.

Again, the reader finds himself caught in a web of unease, of a dread that, with hindsight, has a name...hatred. Again, Gulzar conveys without any direct statement, the helplessness of being caught in a situation beyond control, of watching people being the victims of powers they have never seen. Yet, the poet lingers in the pages, and one uncovers lines that read,' The sky shed its dark attire and draped itself in morning light. The sun woke them up.'

Hope also walks in the midst of the fear and pain the characters experience. Hope in the form of a truck owned by a man simply called Fauji, who drives an odd medley of Hindus across the newly dangerous roads. Gulzar uses the truck to show the many ways human nature can react to danger, and discomfort, fitting in a story within the larger frame as the truck trundles along, skirting danger at every turn. Perhaps the most telling scene is when the travellers, hungry, tired, scared and thirsty realise that, while they have carried as many valuables as space allowed, only one or two of them remembered to carry any food or water to drink. Or perhaps it is when Harinam, an old family servant, stays behind when the family leaves, because he cannot leave Tiger, his dog, behind.

'And if somebody sees you now, '? He quickly removed his cap and showed him his head. ' I have cut my choti — and Ghulam has given me his cap.'

'You mean, for this dog...'

'What "dog", Sardarji? I brought him up like my son. If they say, I shall become a Musalman, but I will not abandon him.'

Tiger, his tongue lolling, came and sat next to Hariram.'

With such quick and easy cameos, the story progresses to wend through a minefield of emotions, and a terrain strewn with bodies and decaying relationships.

The story does not end with the truck reaching its human cargo across the border. It continues into the refugee camps, with the noise and the confusion, the wanting and hoping and the sense of deep loss. And through the story of Moni and her son, Loki, Gulzar touches upon another raw nerve in what could well be a contemporary story. When Moni who gives birth in the camp, and dotes on the son whom she is bringing up as a Sikh, (because her imaginary husband is supposed to be a Sikh), she suddenly realises the boy is the spitting image of the man who raped her, her love turns to bitterness and hate and, unable to avenge herself on her rapist, she throws his child into a well. A contemporary story indeed.

In fact, the last half of the book, even as it traces the survivors of the truck ride through their lives across the border, also holds in itself the seed of growing into a very relevant warning against the lasting and irrevocable effects of communal hatred. Gulzar’s Two is not just his search for a catharsis from the Partition and its wounds; it is a bell sounding out the possibility of other Partitions that could be brewing in the darkness of human minds, rearing and gathering strength, till heavy with its own weight, it must break and destroy, taking innocent lives in its wake.

Though rooted well in the past, Two is as contemporary a tale today as it would have been if it had been written sixty years ago.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated