Australian-Iranian author Shokoofeh Azar is the first Iranian writer to have been nominated for the Booker International Prize. Photo: Booker Prize Foundation

Before Iranian writer Shokoofeh Azar, 48, shifted to Australia as a political refugee in 2011, she had been jailed three times. Her childhood and early career were spent in a climate of hostility and fear under the Islamic regime in Iran. The journalist, author, poet and artist became the first Iranian writer to have been nominated for the 2020 Booker International Prize. Her first novel to have been translated into English from Persian, The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree, steeped in myths and magic realism, tells the story of the suffering, bereavement and loss of an intellectual family in Iran in the wake of the Islamic revolution. In this interview, Azar talks about why writing about the massacre of dissidents in Iran, the historical “catastrophe”, was her social and individual responsibility, writing magic realism on the basis of facts — “everything related to my body, mind and soul can be a fact” — and drawing on the Iranian literary traditions for the novel: Excerpts from the interview:

Shireen Quadri: In The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree, you bring to life the wave of repression in the first decade after the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran. What prompted you to tell this story about this painful part of the country's history? Has the subject been explored adequately in Persian literature after the revolution?

Shokoofeh Azar: The Islamic regime never admitted to the killings of thousands of its opponents in 1988. Only eyewitnesses and the families of the victims testified that the massacre took place. Due to the strong censorship system in Iran, this massacre never officially entered to our literature. It is also due to the taste of Iranian writers (avoiding writing about political events). So, we have no political literature inside Iran after 1979. Iranian fiction writers who have gone beyond Iran’s borders have also rarely written about political and social catastrophes. But memoirs and documentaries have been written more outside of Iran.

For me, as a writer, writing about this historical catastrophe was a social and individual responsibility. Especially that since I have a close friend who lost six to seven members of his family that summer.

Shireen Quadri: Instead of focusing on the macro developments taking place in the country in the throes of Islamic revolution, The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree focuses on one intellectual family of five that was compelled to flee their home in Tehran to a remote village. What did you set out to achieve by focusing on the microcosm of a family caught in the vortex of bigger changes? Did it help to underline the oppression and infractions of the time better?

Shokoofeh Azar: By presenting a general picture of a society, you can probably write an informed editorial, but not a strong novel. To show the general situation of Iranian society, I went from a small part to the whole. In my opinion, providing a detailed and accurate picture could better affect your emotions than a general picture. For example, if I give you a general picture and say, “I ran a lot yesterday,” it won’t affect your senses. It’s even so general that it may not be believable. But if I tell you, “I ran seven kilometres and five hundred and twenty meters last night during torrential rains and thunderstorms on Geelong-Melbourne Road, surrounded by barking dogs and beeping trucks,” I have given you a whole bunch of ideas for believability. By creating this family in my story, I wanted to make it possible for my readers to understand how an anti-revolutionary family in Iran feels.

Shireen Quadri: The novel, though full of political overtones, avoids being overtly political. Told using the device of magical realism, and narrated by the ghost of a 13-year-old girl, Bahar, it beautifully blends the personal with the political. How did you work on striking the delicate balance between the two?

Shokoofeh Azar: Writing a literary novel about politics is as risky as writing a literary novel about love. In the first one, the novel is at risk of becoming a sloganeer, and in the second one, the novel is at risk of becoming a pulp fiction romance or worse pornography.

As you mentioned, there is a very delicate and sensitive border that the author must be aware of before starting the story. Writing a political novel was doubly risky for me as an Iranian. For a few reasons: First, the Iranian regime does not like Western countries to understand how cruel this regime treats its own people. And it was clear to me that also this book could never be published in Iran due to the censorship that ruled the country. Secondly, there was a risk of negative reaction to the book or myself by the regime, after publishing it in English (we have not forgotten Khomeini’s fatwa against Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses). As far as I know, it is unprecedented in Iranian fiction literature that Khomeini (Super Leader and Founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran) has become a fictional character; such a coward character who has delusion, nightmares and gets her pants wet. For understanding the danger of writing about this topic (humiliating Khomeini), you should know that if someone insults Khomeini or Khamenei (the present Super Leader of the regime) in Iran, she/he will be sentenced to death.

Thirdly, Iranian writers also do not like novels with the critical-political themes about Iran. Usually, they believe any story written about Iran politics is a sloganeer and has no literary value, obviously, I disagree.

Shireen Quadri: The novel, which deals with the politicisation of Islam and its disastrous consequences on the country’s culture, people and polity, is steeped in several Iranian myths and legends, references to Iran’s rich literature and philosophy, mysticism and folk culture. There is an unmistakable poetic feel to the entire novel, which has a tragedy at its heart — the tragedy of a brutal end to some of Iran’s best minds. How did you go about working on the novel’s fabric — with a poetic atmosphere soaked evoking the lives of intellectuals and the cultural values?

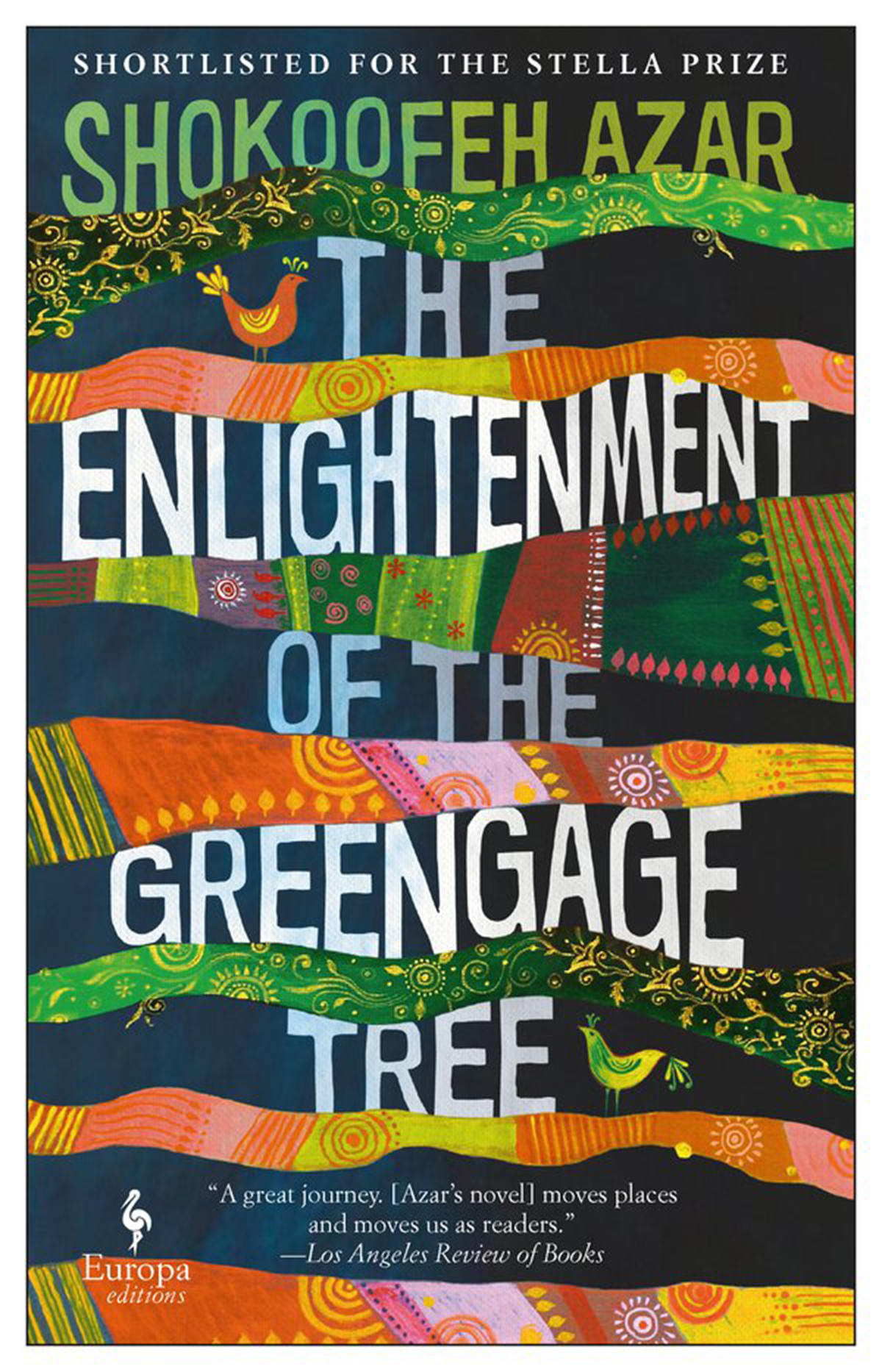

The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree, By Shokoofeh Azar, Europa Editions, pp. 256, $18

Shokoofeh Azar: My writing is very similar to my paintings. Totally impromptu. I am inspired by painting when I write, and vice versa. As I put a white canvas in front of me without any previous plan, design or idea, little by little, I start playing with paints, then the shapes appear, and a layer is placed on a layer, I do the same in my writing. This novel has several layers, characters and deals with several themes. Whatever I didn't like in my story, I quickly deleted it, moved it, reshaped it, or changed its quality, tone or atmosphere. From the very first paragraph, the whole structure of the novel was starting to form in my mind, without me having any plot for the story or characters at all.

In the very first paragraph, as you see, three characters are introduced, a mystical enlightenment and a political execution happened, two main locations are introduced, a traditional Iranian-Islamic custom introduced, a historical-political event mentioned, with a poetic and complex tone.

The whole novel is shaped in the same way; line after line, paragraph after paragraph in the best way that I could write and without any previous plot or idea. Each impromptu idea or scene created after another impromptu idea or scene.

I wrote this novel three times, but the first two times I wrote in a realism style. I soon realized that I hated it. So I started the third version, and in fact, this version was never rewritten. This is what you see in the book. From the very beginning, I wrote and progressed sentence by sentence in the best and most sophisticated way I could. Sometimes I would pause on a paragraph or page for a long time, to find the right information, language and tone. When it was done, I continued writing, just like Persian rug weaving. The rug weaver must weave each line correctly so that they can weave the next track correctly on the previous lane. I wrote like that, and of course, at the same time, impromptu.

Concerning the poetic tone, I would like to say that I did not want to use only poetic literature or vocabulary, but I wanted the poetic atmosphere and poetic thought (Iranian mysticism) to be influential throughout the novel because Iranian literature relies on poetry. Poetry is in the fabric of our culture, and I wanted to show this throughout the novel. For me, in this novel, poetry is equal to being Iranian.

I would also like to point out that research is an essential part of my work. Some people think that magic realism only relies on imagination. I write magic realism on the basis of facts. These facts could be political, historical, religious, mythological or folk beliefs. To write The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree, I read many books and articles. Also, I wrote about 400-500 pages of notes, ideas, news, memories, facts etc. on various topics: mythology, contemporary Iranian history, Iran-Iraq war, the revolution of 1979, executions of Summer 1988, anthropology, sociology of the Iranian people, ancient myths and legends, Zoroastrianism, Geography, soothsaying etc. So, research is an essential part of my writing. I can claim that almost there is no page without a fact in this book. To me, as a fiction writer, the fact is not only history, science or something that is mentioned in a book or approved by reliable resources. The fact, to me, also can be a dream that I had five years ago or an emotion that I had experienced when I was a child. Everything related to my body, mind and soul can be a fact to me.

Shireen Quadri: The novel boasts of some really interesting characters, the mother, for instance? How did they come to you? What kind of stories have you heard about those times in the family?

Shokoofeh Azar: I put the real name of my parents on the parents in this novel, perhaps because I missed them a lot. And every time I wrote about Rosa, I imagined my mother when she was young, tall and slim with short hair, brown skin and with a polite smile on the corners of her lips before people. But it is interesting to know that my mother’s character is very different to Rosa’s character in this novel. Maybe Rosa, who I wrote in this novel, is the kind of woman who I admire.

My real mother is a very devout, conservative, hardworking, quiet, calm and submissive mother. She endures all hardships and sufferings in silence. Her courage is summed up in her motherhood and motherly sacrifices, which, of course, is very valuable. She is a great mother — a mother who every child wants to have. However, this regime also changed my mother's character. My mother, little by little (with influence from her five children, especially three of us) became braver and sensitive to social issues. She was even involved with the street protests against the regime alongside us, her five children. I am filled with joy when I remember how my mother in the street protests moved her fist in the air and slogan: “Down with the dictator. Down with the dictator.”

Anyway, Rosa in the story comes from the idea of a fascinating woman/mother in those circumstances of the story: The woman who is brave enough to say “no”, be independent and have enough courage to abandon everything behind to find who really, she is. However, some parts of her character are inspired by the women around me. For example, I knew a woman who, five years after the hijab became compulsive in Iran, in 1981, did not leave the house in protest to avoid being forced to wear a headscarf. Or, for example, my mother used to write poetry in her youth. Or my mother and father met in the same mountain (Darband) that Rosa and Houshang in the story met. And my father, like Houshang in the story, proposed to my mother in the same day, and my mother accepted right there. Or the scene of Rosa and Houshang’s death, when a stranger arrives and tells their children to stop crying so that Rosa and Houshang can die easily; this exactly happened with one of the women I knew.

Shireen Quadri: Your novel, and your nomination, is vital in many sense. You are perhaps the first Iranian-Australian to be on the shortlist. You are the first Iranian to have been nominated for this award. What does the award mean to you personally?

Shokoofeh Azar: It has been the dream of Iranian writers for decades to be able to display rich Persian literature in the world level. Farsi literature and language date back to thousands of years and the first human rights cylinder (the Cyrus Cylinder), One Thousand of One Night and Book of Arda Viraf (the book which inspired Dante Alighieri when writing Divine Comedy) is written with. I am very honoured that my writing has had this chance. Not only for myself but also for the Iranian literature, Iranian people and for my family, whose work has been formal or informal in writing, journalism and poetry, for at least five generations. I feel that my father, grandfather and grand-grandfather (who was the writer of Qajar palace in 19 century) would have been very proud if they were alive.

Also, I should mention that the shortlisting of my book at the International Booker Prize has made Iranians, many of whom are not even literary people, happy. ‘Amid all the bad news in Iran, we are glad that you made good news,’ they wrote for me on my social media.

Shireen Quadri: Tell us about some new Iranian writers who are chronicling the lives of Iranians who deserve to be read by the wider world.

Shokoofeh Azar: As I mentioned above, due to severe censorship in Iran, unfortunately, we do not have political and social literature in Iran. Fiction authors living outside of Iran have also paid less attention to these topics, either their books have not been published in English or I have not seen them. One of my dreams is to set up an institute to translate Farsi literature and mythology into English.

However, I would like to take this opportunity to introduce some non-fiction books written by Iranians about contemporary Iran that have been published in English:

• Olya’s Story by Olya Roohizadegan (Oneworld, 1993)

•The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad (Little Brown and Company, 2018)

• Politics and Culture in Contemporary Iran: Challenging the Status Quo by Larry Diamond, Abbas Milani. (Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2015)

• Reading Lolita in Tehran by Azar Nafisi, (Random House, 2003)

• The Persian Sphinx by Abbas Milani (Mage Publishers, 2000)

• The Shah by Abbas Milani (St. Martins Griffin; 2012)

• Inquiry Into the 1988 Mass Executions in Iran by Tahar Boumedra, Azadeh Zabeti (Create Space Independent Publishing Platform, 2017)

Shireen Quadri: The lockdown after the pandemic has brought the entire world to a halt. How have you been holding up? What do you make of the Iranian response to the pandemic? How do you see your writing changing after this?

Shokoofeh Azar: Just as the lockdown started in Australia, it so happened that I fostered a ten-year-old Afghan girl. The experience is exciting and, of course, challenging. For the past three months, my daughter, me and my new daughter have been trying to get to know each other and learn how we can be a family. In the same time, we experienced home-learning, which was not a comfortable experience for me. Making two playful girls sit, and concentrate on their study, was the difficult part of my every morning. I also had much less time for writing. My only time was midnight when they have slept. But thankfully schools have opened, and I am back to my regular routine. I usually work 10 to 12 hrs a day: six-hour daytime (school hrs) and 4 to 6 hour night and midnight time (when kids have slept).

As usual, the Iranian government managed the situation terribly. They announced the lockdown very late. Coronavirus testing is costly and many people cannot afford it at all. On the other hand, the government soon ordered the reopening which has created a new wave of positive cases, unfortunately. Simultaneously with the lockdown, an earthquake and a flood occurred in some cities, and domestic violence and several horrific homicides and suicides occurred.

Since I need the space of time for events to find their way in my writing, I cannot say how exactly it is all going to affect me in the future.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

There is nothing to say because while reading this we too in Iran and we can feel that happy family, the rules and regulations of the country. We can enjoy the presence of jinn, through magical realism and the life Beeta she turned to a mermaid. Everything that touching, and its sure that if we read this we can feel that we too with Bahar. I like this work and Thanks to the author that for giving me an opportunity to know about the beautiful culture and stories of Iran..... Thanks....

Febin shahna

Jun 28, 2021 at 10:15