A few words, placing the title in context, ‘writing the new woman’, instantly spark interest in these translations of collaborative writing, from over 90 years ago. The translators are to be commended for their work. As an Odia, I can relate to the subtle nuances of the Odia language, and the turn of phrases, that will also endear litterateurs.

Basanti began in serial form, in Utkala Sahitya, from 1924-1926 and was later published as a novel in 1931. It was then republished in 1968.

Nine authors, including three women, were part of the creative ‘Sabuja’ group — individuals with the desire to create a “language that is green”, evoking the Romantics,‘going back to nature’ and underscoring simplicity. Ananda Shankar Ray, Baishnab Charan Das, Harihar Mahapatra, Kalindi Charan Panigrahi, Muralidhar Mahanti, Pratibha Devi, Sarala Devi, Sarat Chandra Mukherjee and Suprava Devi were all dedicated to the cause of social justice, education for women, their rights and choices. There were similar writing collectives in the literature of Bengal at the time, for instance, Baroyari by 12 authors. Inspiration may have been derived from The Spectator — it flashes to mind, with its serialised essays. Also, from Charles Dickens, who wrote in sequential form and is credited as the founder of serial publishing, with his Pickwick Papers by Boz (from 1836-1837).

A new narrative was being experimented upon. Each author was to write two chapters and send these to one author for approval. There were a few other rules to be adhered to. The translators have not strayed from the original narrative and the pace of the chapters flow in seamless order.

It was an enlightening time for the privileged class in Odisha, with its access to books and newspapers, for we find mention of the suffragette movement in the UK and USA. Also, allusions to Romain Rolland, Keats, Yeats — whose works had impinged inquisitive minds, with the desire for change. Coupled with these thoughts, the writers had their visions for the future, gleaning knowledge from our own erudite Tagore and the ancient wisdom of Kalidasa.

Yet, as we are all aware, tradition placed certain restrictions on a woman, especially a married one and demanded their observation. These were branded into ‘her’ soul from an early age. In the protagonist, Basanti, however, we discover a familiar 21st-century well-educated, well-read, articulate woman. She questions and can debate a moot point. She writes for an Odia monthly, Nababani, on ‘The Place of Women in the World’, stating boldly — at that juncture in history — “for a place for women outside the world of men” — for a fulfilling life. This sentiment was being echoed the world over, including Europe and the Americas. Are Basanti’s characteristics, that had once endeared her to her future husband, Debabrata, the entwined yet inflexible components of the final ‘fatal flaw’, that lead to a change in her character, and their relationship, as the novel progresses?

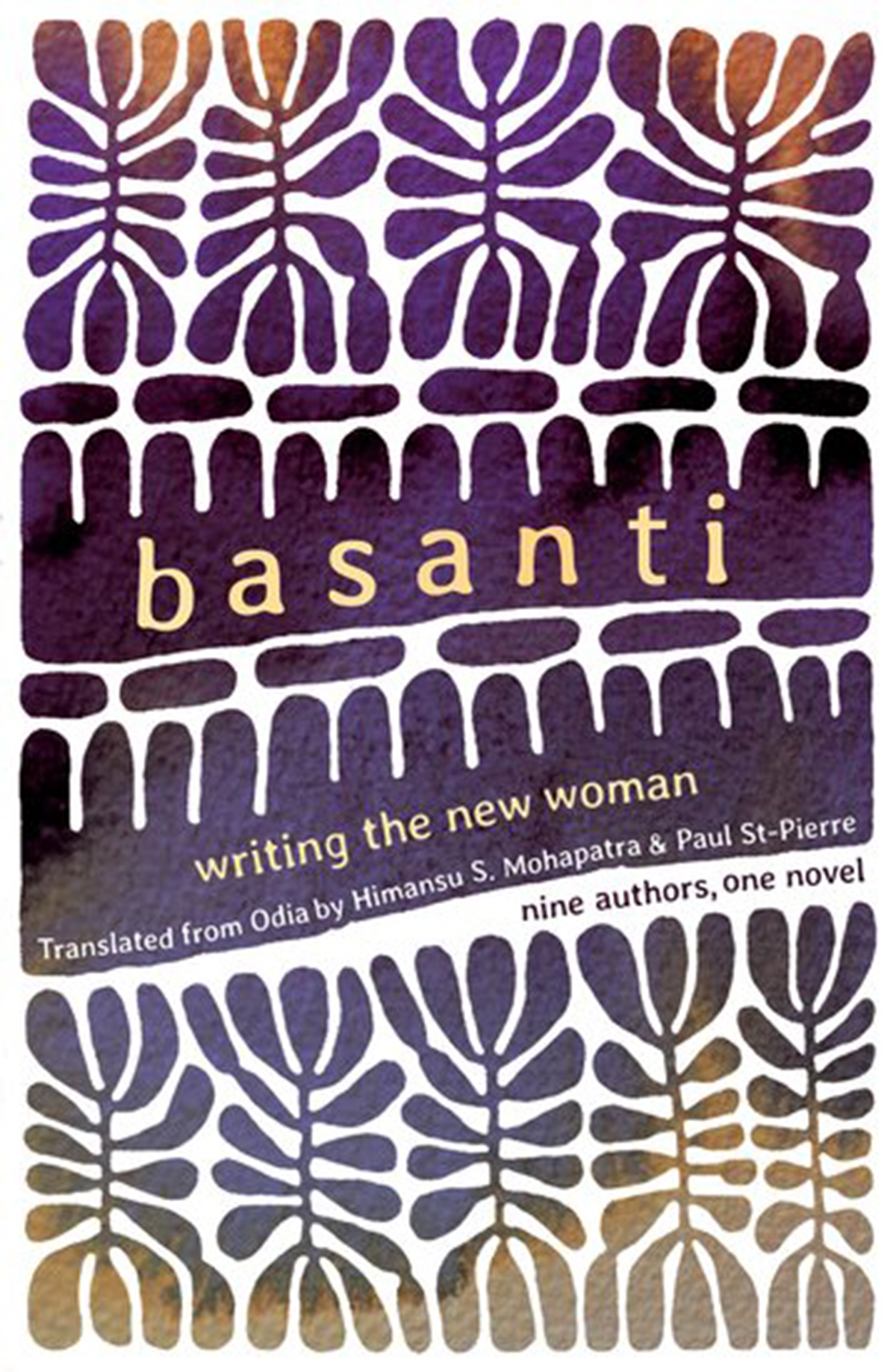

Basanti: Writing the New Woman — Nine Authors, One Novel

Translated from Odia by Himansu S. Mohapatra and Paul St.Pierre

Oxford University Press (2019), pp. 276, Rs 550

It is easy to cast Basanti’s ‘Deba bhai’ as the deuteragonist. An idealistic student, he has no qualms in upsetting the social order of the time. He has chai with anyone. He goes with a friend to a basti razed by fire to help, even though the inhabitants are of a different caste. He encourages the education of women in debates at college. Debabrata dares to marry for love and out of a sense of duty, biding by Basanti’s mother’s dying wish. Marital tension soon arises from their relocation to his zamindari, and an unwelcoming, stoic mother. Two intelligent minds, bound by love, are put to test here.

Basanti, one the one hand, strives to ensure her mother-in-law cannot fault her behaviour or her completion of household duties. She bites back retorts, as the domestic helpers and neighbours come over to gossip and begin to slyly cast aspersions on her upbringing. On the other hand, Basanti’s determination for change compels her to open a school for girls, against all odds, that she runs with her friend and sister-in-law, Nisa. She also dispenses homeopathic medicines to the poor.

Debabrata is no tragic hero. He lacks the strength, the spirit to overcome feelings of remorse, in being unable to provide Basanti with the best of everything. He is unable to break her indomitable will, or to denounce her writing publicly, on the need for women to be independent beings. Shades of Othello emerge as jealousy also rears its ugly head. Basanti accepts all that happens with dignity. The ending is unexpected.

For many of us, educated in English-medium schools, with perhaps a weekly class in our Mother Tongue, for two years, would have lost the topicality and modernism of women’s thoughts and experiences during this period in Odisha’s history. Basanti’s thoughts resonate today, though voiced almost a century ago.

Himansu S. Mohapatra is former professor, Dept. of English, Utkal University, India, and Paul St. Pierre is former professor, Dept. of Linguistics and Translation, Universitie de Montreal, Canada. The nine authors are: Annada Shankar Ray, Baishnab Charan Das, Harihar Mahapatra, Kalindi Charan Panigrahi, Muralidhar Mahanti, Prativa Devi, Sarala Devi, Sarat Chandra Mukherjee and Suprava Devi

(This review was part of May 2021 issue, which was delayed due to the pandemic and released on August 3)

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated