Photo by Taryn Elliott

From scribbles to final touches, For the Hope of Spring emerges as a celebration of hybridity. This hybridity is not just in content but also in form, as Sen dabbles in various styles

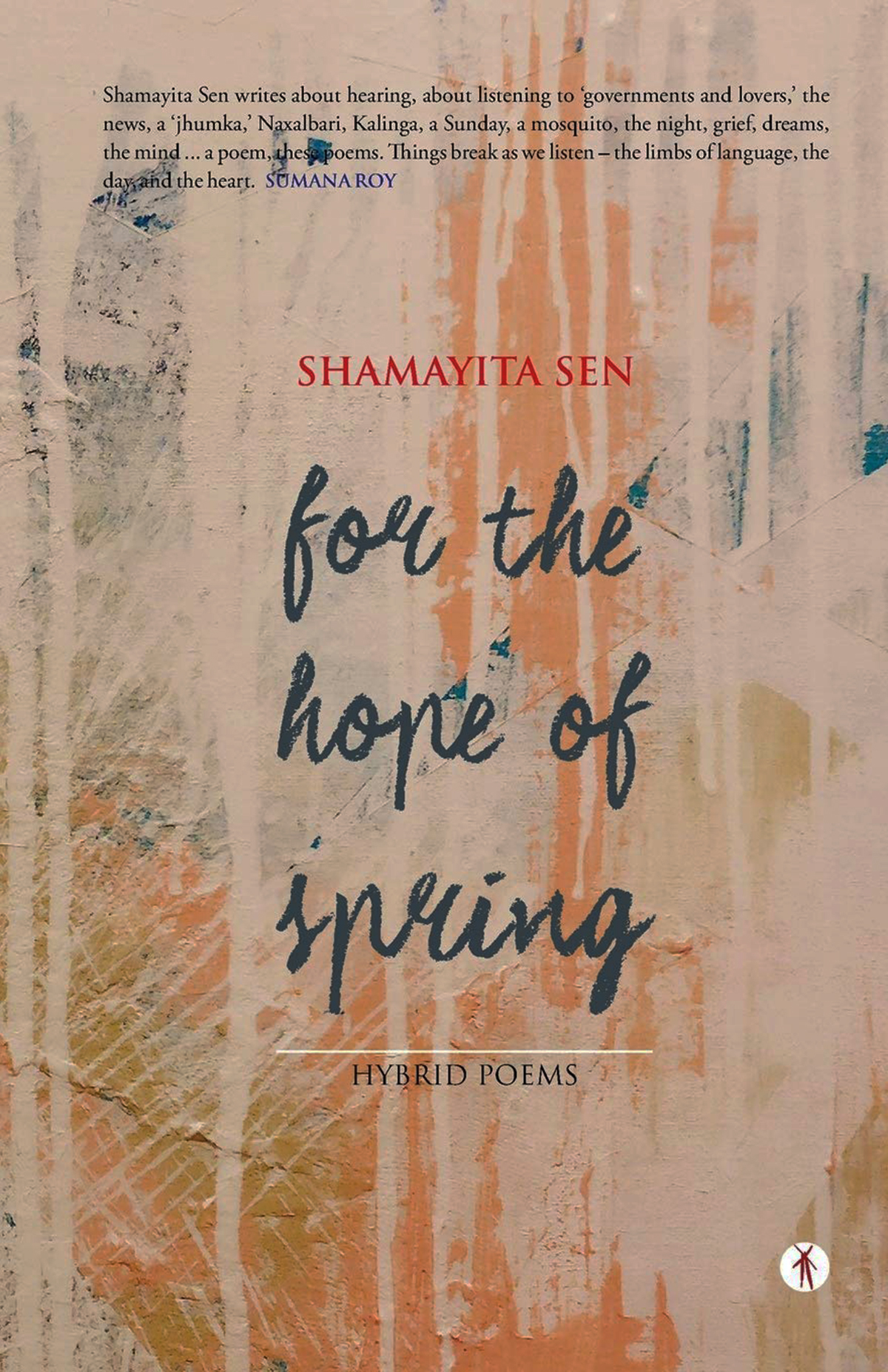

At first glance, the crisscrossing lines of orange, yellow and teal on the cover of Shamayita Sen’s debut collection of poetry, For the Hope of Spring (Hawkal Publishers), look like truant streaks of sunlight that have filtered through window bars to draw intricate patterns on the ground — hazy but bright, static yet mobile. They are soft, very soft, and remind you of how it feels to wait in hope of spring. On the second glance, however, the sharp jabs of these lines become apparent. Not as soft as you initially believed them to be. The lines then become scars left by the scribbling of the sharp edge of a knife, akin to those wrinkles life leaves on us. In the midst of this amalgamation of hope and violence, you find the title of the collection stamped in a flowy cursive in the centre. Underneath this is the subtitle — “Hybrid Poems” — in bold.

It is here that I pause, wondering what exactly could this mean. I Google the word “hybrid” and am pleasantly surprised to find that its root goes back to the Latin word ‘hybrida’ which means the ‘offspring of a tame sow and wild boar, child of a freeman and slave, etc.’. In retrospect, I feel nothing could have been a better way to describe this set of forty-seven poems. Sen’s poems refuse to surrender itself to the limitations of a single category. It hovers midair, occupying the liminal space, subscribing neither to this nor to that and, in the process, becoming simultaneously both and neither. Her words duly obey, sometimes leaking out in tame whispers, sometimes stirring up a storm with wild abandon, sometimes unabashedly flaunting its power of free expression and, at other times, shrinking in extreme trepidation.

Talking about her creative process in the Preface, Sen mentions how this collection was born out of “scribbling notes to publishing poetry” and it is perhaps these scribbles that intensify this ungraspable nature of her poems. Her language is punctured with gaps and pauses that cause the images to break down and reveal its raw viscera. This sense is further augmented by how the book has been fragmented into three parts: “On Dissent”, “Grief and Other People”, and “Love, Healing, etc.” Moving from the world to the home to the inner-home or the mindspace, each of these segments present encounters that keep getting dangerously close to the core of one’s being where the psyche is caught up in a constant cycle of collapse and creation. These “dream images”, as Sen refers to them herself, channel a steady flow of stream of consciousness where the personal and the political come together, making it difficult to understand where one begins and the other ends.

This sense is overtly present in the first section of the book, where “wars and rage” can co-exist on the same plane as “mutton on a Tuesday platter” or “erogenous zones on a premarital bed”. Here, the heart-wrenching tragedies that the nation has witnessed over the wretched year of 2020 can easily escape into dream vignettes creating “a moment of confusion” where the self cannot be distinguished from the other. In the middle of a perfectly solo outing, one can suddenly find their complacency thoroughly challenged on finding the art of “liv(ing) well” getting inexplicably tied up in similes to those Kashmiri homes destroyed by stray bullets. As far as length goes, this segment is the shortest as compared to the other two, containing only eight poems. Yet, within this limited span, Sen manages to traverse a surprisingly wide range, be it in space (from Kalinga to Naxalbari to Delhi to Kashmir) or time (from Sati to Partition to the Lockdown to Amphan).

For the Hope of Spring: Hybrid Poems, By Shamayita Sen, Hawakal Publishers, pp. 90, Rs 350

As we move further into the book, its ambit grows wider but more vertically than horizontally. Here the personal impinges upon the personal as the scribbles of the poet’s mind meet to only disperse and then recongeal, again and again, till it attains collective proportions. The sights and smells of cities waft through, coagulating with one’s own memories of “Street food”, “City lights” and “Coffee”. Lived cities blend into hometowns as nostalgia seeps in from one to the other. Period cramps to postpartum depression, phobia to therapy, rape to consent, everything finds place in these rendezvous of the ‘I’ with the ‘us’, “over measured coffee spoons”. Each of these pieces explores different kinds of trauma through their respective lenses. These are personal traumas and one can almost see the lives that might have inspired such tales. Yet, surprisingly, these are also traumas that all of us have faced some time or the other in our lives. Repressed memories that we are scared to stir up, “gaping wounds” of “past lovers and lost lives”, overwhelming grief that can “clutch you by your throat”, remnants of abuse on the body and soul, pain, desire, loss and hope — all of them create a montage of life sequences that is the poet’s but also mine and yours.

By the time we reach the third part of the book, this division, too, crumbles. From mine and thine, the poems move to an exploration of the mine within mine. The searing savagery of trauma that weighs heavy on the previous two sections, growing in intensity with each passing passage, seem to find a cathartic cleansing in this part. With memories of safety pins tucked in Maa’s anchol to the last trip to a hill station taken with a parent now no more, these poems finally let the grey clouds of the mind, pregnant with heavy rain, to shower down in soft drops. These poems are intimate in how they tease out tender moments, carefully curated from the mind’s innermost storage bank. They bring back much remembered memories like the smell of the first meal served by Maa on returning home after long, numbing memories of seeing one’s father turn to ashes in an electric chulah, false memories of figments of imagination or forgotten memories that have become “a lost strain of thoughts”. There is pain but it is a pain that becomes one’s becoming. It is no wonder, therefore, that the last poem of this section is titled “Autobiographical Much?” Having washed off all the excesses, it is only at the very end that a poet can be born.

From scribbles to final touches, For the Hope of Spring emerges as a celebration of hybridity. This hybridity is not just in content but also in form, as Sen dabbles in various styles. Sometimes her poems are like a garland of short sentences threaded together. Sometimes they are in block paragraphs, very much like prose. Sometimes they have titles, which you might later discover, is actually the first line of the poem. Sometimes, the first line of a poem is in fact a response to the title. Yet all of them share one thing — they are filled to the brim with a rich tapestry of images. While they add a lot of flavour to the whole experience, it can also get quite overwhelming at times. However, being overwhelmed is not always bad as it is only in the throes of such surplus that one can begin the process of purgation and truly bring forth spring. This is what Sen’s debut collection of poems does.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated