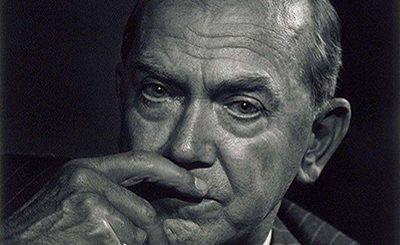

Author and Man Booker Prize for Fiction juror Lila Azam Zanganeh at the announcement of the 2017 shortlist. Photo courtesy of Man Booker Prize

Lila Azam Zanganeh is the author of The Enchanter: Nabokov and Happiness (Norton, 2011). Azam Zanganeh was born in Paris to Iranian parents. After studying literature and philosophy at the École Normale Supérieure, she moved to the United States to become a teaching fellow in literature, cinema, and Romance languages at Harvard University. In 2002, she began contributing literary articles, interviews, and essays to a host of American and European publications, including The New York Times, The Paris Review, Le Monde, and la Repubblica.

She is fluent in seven languages (English, French, Persian, Spanish, Italian, Russian, and Portuguese) and is the recipient of the 2011 Roger Shattuck Prize for Criticism, awarded each year by the Center for Fiction. She writes and lives in New York City, and is at work on a new novel titled A Tale for Lovers & Madmen. Azam Zanganeh serves on the Board of Overseers of the International Rescue Committee and the Advisory Board of Libraries Without Borders. Since September 2015, she has served as the Chair of Programs for Narrative 4, a global story-exchange organization that promotes radical empathy. Up until the end of 2011, Azam Zanganeh served on the advisory board of The Lunchbox Fund, a non-profit organization which provides a daily meal to students of township schools in Soweto of South Africa.

Besides Lila Azam Zanganeh, the panel of judges includes Baroness Lola Young, who chairs the jury, Sarah Hall, Colin Thubron and Tom Phillips.

The shortlisted novels are:

1. 4321 by Paul Auster (USA), published by Faber & Faber

2. History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund (USA), published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

3. Exit West by Mohsin Hamid (UK-Pakistan), published by Hamish Hamilton

4. Elmet by Fiona Mozley (UK), published by JM Originals

5. Lincoln in the Bardo, George Saunders (USA), published by Bloomsbury Publishing

6. Autumn by Ali Smith (UK), published by Hamish Hamilton

In an interview with The Punch, Lila Azam Zanganeh says that the novel summarizes consciousness while formally always reinventing itself. “The imagination is what defines us as a human race. It’s connected, as Blake believed, to nature, in its infinite sprawl, but also to empathy, the binding force of the 21st century if it is to survive itself. The more we read, the better we are able to empathize,” she says.

Excerpts from an interview:

Nawaid Anjum: How was the process of selecting the longlist, out of the 145 novels submitted this year, for you?

Lila Azam Zanganeh: It was less painstaking that we all imagined, I believe. The best novels stood out very naturally and obviously.

Nawaid Anjum: Three notable novels, which were on the 13-book longlist — Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, Arundhati Roy's The Ministry of Utmost Happiness and Zadie Smith’s Swing Time — could not make the cut for the shortlist. As a writer analysing their works, how would you see their latest offerings?

Lila Azam Zanganeh: All three of these novels are doubtless very accomplished. But part of the process is making a collective decision, in which we choose not only one single book but a collection of books as a result of a deliberative, democratic process. There are give-and-takes, and I’m very pleased with the shortlist as a result of this year-long, incredibly dynamic and enriching discussion. I think as judges we were quite good at listening to each other and at times changing each other’s visions, in ways I believe eventually paid off for the books themselves.

Nawaid Anjum: What worked for the six novels on the shortlist? As a member of the jury, what did you set out to look out for in the qualifying novels?

Lila Azam Zanganeh: The six novels on the shortlist each are innovative and stylistically unique. Each of them speak of and to this world — its defining fractures, endemic violence, but also to its wild heart, and immense beauty.

Nawaid Anjum: Could you talk about the distinct qualities of each of the shortlisted novels that make them compelling stories of our times?

Lila Azam Zanganeh: Elmet by Fiona Mozley and History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund are both stories of lives on the margin of society, and how seeing from the margins actually allows us to redefine the center, in sharper and at times much grimmer ways. Exit West by Mohsin Hamid is the story of migration told through a kaleidoscope of angles and a story that at times reads like a tale for the 21st century. Autumn by Ali Smith is an elegy for the present, in post-Brexit Britain, it questions what it means to be displaced and dislocated in one’s own country. Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders is, in a certain sense, a ghost story retold, a tale of otherworldliness, yet profoundly rooted in history and the meaning of empathy. 4321 by Paul Auster could be seen as a story about alternative universes, string theory or virtual reality, or more simply, like a Cubist self-portrait in four parts.

Nawaid Anjum: Half of the writers on the shortlist this year are from America — Paul Auster, Emily Fridlund and George Saunders. In certain quarters, this has revived anxieties about the 2013 decision to open the prize to any novel written in English and published in Britain, regardless of the author’s nationality, rather than restricting it to writers from Britain, Ireland, Zimbabwe and the Commonwealth. How would you respond to such anxieties?

Lila Azam Zanganeh: I have no anxieties whatever. I am absolutely convinced that this is better for the prize and thus better for literature in general. The opening of the prize to the world, essentially, turns it into the most important prize in the world after the Nobel, ahead of the Pulitzer Prize or the National Book Award in the United States. If you want to matter, as a prize in the arts, you have to be an international prize. The world and its writers are increasingly transnational. Many of us are writers born in one country, descended of another continent altogether, and writing in the language of yet another. This is my own case, as a French-born writer of Iranian descent who chose in her twenties to write in English. The restriction of the Man Booker Prize to Britain and a handful of countries would seem provincial at this point in time, in a moment when what matters — especially in the post-Brexit era — is that a great English prize extend its arms to the world, and not restrict itself to its own borders, or those of its former Empire. So in this context, as judges, we are overlooking nationality completely. And if the best writers are from Zimbabwe, or the United States, it’s an accident of birth. I believe it makes writing in English more competitive, and ultimately better. If more British writers win in the future, it will mean that they stand to be among the very best writers in the entire world.

Nawaid Anjum: Could you tell us about your appreciation of the form of novel? Who are some of the greatest novelists, both past and present, you have admired?

Lila Azam Zanganeh: I think that at its very best, the novel does what only the novel can do, which is to say, it summarizes consciousness while formally always reinventing itself. Some of my favorite novelists are Nabokov, Joyce, Proust, Yourcenar, and a few of our shortlisted writers, though I can't say which ones just yet!

Nawaid Anjum: In our troubled and fractured times, what role do you think fiction can play in bringing individuals, nations and societies together?

Lila Azam Zanganeh: I think it can play a crucial role. The imagination is what defines us as a human race. It’s connected, as Blake believed, to nature, in its infinite sprawl, but also to empathy, the binding force of the 21st century if it is to survive itself. The more we read, the better we are able to empathize. And there is strong evidence of positive correlations between developing the imagination and diminishing violence, in refugee camps, for instance. I work on these issues personally, through two organizations I'm involved with, and it's been extraordinary to see that everywhere we spread books and storytelling, communities tighten, and resume speaking, and also, in time, become better at forgiving, which is to say at imagining themselves anew.

Comments

*Comments will be moderated