Upamanyu Chatterjee. Photo courtesy of Speaking Tiger

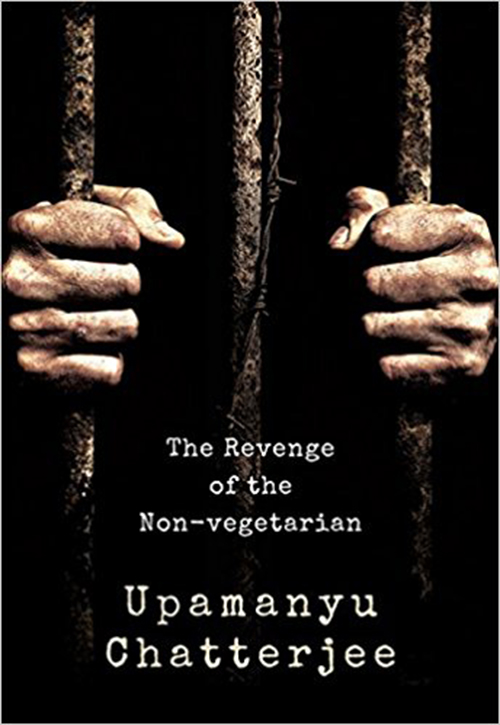

The Revenge of the Non-Vegetarian is tightly conceived and though slim, packs a punch, dissecting India’s descent into atavistic madness over meat and its flawed judicial system

In Upamanyu Chatterjee’s fiction, fantasy, fairy tales and reality blend seamlessly to evoke dark tales about bureaucratic India. As Chatterjee unfolds India’s darkness layer by layer, light remains never far behind as he laces his stories with humor, wit and charm. Chatterjee’s new novella, The Revenge of the Non-Vegetarian (Speaking Tiger), is a searing meditation on the politics over meat, which has defined much of the contemporary political discourse in India, with cow vigilantes launching the lynching epidemic across the length and breadth of the country.

Thirty years after his debut iconic novel —English, August, the story of Agastya Sen, a young westernised Indian civil servant ensnared by women, literature and drugs — made waves, capturing the imagination of readers across the globe, Chatterjee is back with another dark, satirical tale, suffused with wry humour which has become the trademark of his fictional universe which draws on his experiences as an Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer. Currently serving the Indian government as Joint Secretary on the Petrol and Natural Gas Regulatory Board, Chatterjee has his fingers on the pulse of the stifling tentacles of India’s babudom, its absurdity and tedium.

The Revenge of the Non-Vegetarian, a murder mystery, set during 1949-1972, is a reflection on the slow and sluggish judicial system in India where litigations drag on for decades. It echoes the contemporary debate over morality of meat-eating which has triggered India’s disturbing descent into primeval bloodletting. Scores of men have been lynched for transporting cattle everywhere across the country, and many over the mere suspicion of having consumed beef.

The novella opens with Basant Kumar Bal, a domestic servant, recounting the fire that had swallowed up the single-storey house and the six-member family of Nadeem Dalvi, a subordinate mamlatdar of Batia, where Bal has been working as a help. In his statement to the police, Bal narrates that he was woken up by the midnight mooing of cows and the “frenzied, terror-crazed wailing” of the dog after Dalvi’s house went up in flames, fifteen feet in the air. In the subsequent chapter, we meet Madhusudan Sen, ICS, who appeared in English, August as Agastya Sen’s disgruntled father. It’s 1949. And Sen is the sub-divisional magistrate of Batia in Narmada Pradesh. When Sen visits the site of the ghastly occurrence, he sees “walls blackened by soot, windows with neither glass or frame, doorways with no doors… verandah reduced to jagged, charred stumps, the tiles of the roof, shattered, singed lay all anyhow everywhere, on the ground about the dwelling and inside, on the floor… everything reduced to soot and cinders” just before the day the Dalvis were to celebrate the engagement of their daughter. Bal, who slept in the outhouse next to the cowshed, is apparently the only eyewitness to the conflagration.

The magistrate’s residence is a late 19th century bungalow on temple road in the Civil Lines Area, in the “blessed shadow” of the patron deity of 1,000-year-old Dayasagar Adinath temple, which lies at the summit of the knoll behind it. “The patron deity was fiercely ascetic than most incarnations, reverential beyond compare of life in all its forms" writes Chatterjee. On the second day of his arrival in Batia, Sen discovers, through his cook Murari, that a large swathe of the area around the temple was vegetarian “out of respect”: “Meat, fish, eggs, liver, not allowed. Not even onions and garlic,” informs Murari. Very soon, Sen, a Bengali “accustomed since childhood to some non-vegetarian item in every meal: Meat, fish, eggs, liver, beef” finds his “principal protein and cholesterol supplier” in Nadeem Dalvi. After all six members of his mamlatdar are gutted in the fire, Sen takes an oath: He will not touch non-vegetarian food till the culprit behind the death of the Dalvis is hanged. Arif Dalvi, junior engineer from water works, is Nadeem’s younger brother, who takes on the task of supplying meat to the magistrate. The magistrate, meanwhile, fires his cook and gets another: “The temple — and not a lowly mortal’s kitchen — is the place for one who considers touching onion and garlic a sin.”

The novel revolves around Sen and Bal, shuttling between past when Sen was finding his way around in Batia — taking baths with “tingling well water” and finding solace in Cutty Sark and Gold flake — and the sequence of events that led to the tragedy that finished the mamlatdar’s family and Bal’s subsequent incarceration, awaiting trial. The case, as expected, drags on for decades. An ideal prisoner with no visitors queuing up to meet him, he is advised to plead Not Guilty. Then, the usual rigmarole of the sickeningly slow judicial process — the chargesheet, the trial.

Sen, meanwhile, turns vegetarian and even goes to the extent of getting an abattoir close its shutters, having witnessed the “savagery and torture” of poultry and cattle. Sen says: “This blood sport with sacred life is but to create some cutlet or curry or kebab for the dinner tables of the carnivores.”

On June 24, 1951, Sen, the first native member of the Indian Civil Services (ICS) to serve at Batia, leaves the province for the last time, entrusting Arif Dalvi, with a task — “you’ll have to be my eyes and ears…you have to watch the case, follow it, for a decade or two, perhaps even more…it was never in our hands, I know; it won’t, for that reason, slip out of our memories.”

The verdict in the case of Basant Kumar Bal versus Narmada Pradesh, is pronounced early in 1956 and Bal gets death for having “butchered and burnt six innocent human beings because he, inter alia, wanted to enjoy, all by himself, an entire pot of a preparation of beef.”

The court of Justice Shyamlal Goyal rejects the “revenge of the non-vegetarian” theory that assumes the Dalvis half-starved his employee and not provide him three square meals a day, because of which the accused, deprived of adequate nourishment, became mentally so disturbed, so aggrieved that he was in a sense, goaded, compelled to retaliate in the hellish fashion.”

Bal spends the next 17 years of his life in the prison as the judgment of death of the Sessions court needed to be confined by the High Court. Awaiting hanging, he has two rapist murders and one child kidnapper-killer — all vegetarians — as company. They’d greet him as go-maas-a-haari, beefeater.

In 1970, Sen is back in the scene after 21 years as the new Inspector General of Prisons of the Central Jail where Bal is behind bars. But by then, a mercy petition has been sent to the President of India to save Bal albeit it is addressed to King George VI.

In December 1972, district and sessions judge issues the warrant of execution of Bal’s death sentence. In the end, Sen has his revenge as writes to Arif Dalvi, who had migrated to migrated to Rawalpindi in 1957, that “once or twice a year, some Satanic villain should dangle at the end of the rope”.

The Revenge of the Non-Vegetarian is tightly conceived and though slim, packs quite a punch, dissecting India’s descent into atavistic madness over meat and its hopelessly flawed judicial system.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated