Vivan Sundaram at Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in New Delhi. Photo: The Punch

Vivan Sundaram’s retrospective “Step Inside And You Are No Longer A Stranger”, on at Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in New Delhi till June 30, careens through different shifts in Sundaram’s art practice and his explorative approaches

New Delhi-based artist Vivan Sundaram, 75, aims to disrupt and disturb the viewers. His retrospective, “Step Inside And You Are No Longer A Stranger”, curated by Roobina Karode, is on at Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in New Delhi till June 30.

The retrospective careens through different shifts in Sundaram’s art practice and his explorative approaches. On display are around 180 artworks which include drawings, paintings, sculptures, collages, photo-montages and installations created over a period of five decades. A key highlight of the exhibition are a suite of 12 large paintings made in the 1980s, including The Sher-Gil Family, Guddo, Two Friends, Ten Foot Beam, Big Shanti,

among others.

Son of Kalyan Sundaram, chairman of the Law Commission of India (1968 to 1971) and Indira Sher-Gil, sister of noted artist Amrita Sher-Gil, Sundaram was born in Shimla in 1943. He studied painting at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Baroda (BA, 1965) and at the Slade School, London (post-graduate diploma, 1968, on a Commonwealth scholarship). In London, he had the opportunity to meet and learn from R.B. Kitaj, the American artist who had a significant influence on British pop art, with his figurative paintings featuring areas of bright colour, economic use of line and overlapping planes which made them resemble collages, but eschewing most abstraction and Modernism.

From 12 Bed Ward series, trash, 2008

At Slade School, Sundaram attended the course on history of cinema, and later a course on the Second World War which introduced him to many tragic moments of history. A visit to Poland in 1989 gave him a chance to visit Auschwitz, and an impetus to start the series of large charcoal drawings titled “Long Night”.

During the early 1970s, Sundaram was actively involved with the student movement, and worked with activists. This activism later manifested in his involvement with the work of the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust (Sahmat), of which he is a founder member and trustee. A keen organiser, he initiated the Kasauli Art Centre in his family house in Himachal Pradesh in 1976. It has hosted numerous national and international workshops and theatre productions.

Sundaram was part of the narrative-figurative school of painting that emerged from the Fine Arts Faculty, MSU, Baroda and included the practices of painters like Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, Bhupen Khakhar, Sudhir Patwardhan, Jogen Chowdhury and Nalini Malani. He participated in the seminal exhibition “Place for People” (1981) with his works, Guddo and People Come And Go. The “Place for People” gave him the courage to handle mortality and melancholy vis-a-vis his personal history in The Sher-Gil Family (1983-84).

In 1991, Sundaram drew upon the horrors of the Gulf War in a series of works using engine oil and charcoal. A major section of this retrospective is devoted to this seminal series wherein Sundaram first began to explore the spatiality of installation art.

Sundaram’s experiments with alternative media led to a shift away from painting in 1991. With “Collaboration/Combines” at Gallery Chemould in New Delhi in 1992, Sundaram became one of the first artists in India to produce installation art. The series “Riverscape” (1992-93) used charcoal on paper alongside engine oil and steel, fashioning three-dimensional elegies to a decayed environment. Sundaram’s 1993 installation “Memorial” responded to the December 1992 destruction of Babri Masjid in Ayodhya. “House/Boat” (1994) narrated the trope of migration away from one’s home. His 1999 solo exhibition “Shelter” drew upon the politics of “home”. In the show, he used the structure of a bunk-bed to explore issues of sleep, desire, and sexuality.

In 2001-2, Sundaram began the photomontage and video project “Re-take of Amrita.” Manipulating photographs of Amrita Sher-Gil taken by Umrao Singh (Sher-Gil’s father and Sundaram’s grandfather), the artist complicated issues of preexisting artistic agency and familial relationships and history. The series employed the concept of the archive, and drew also on The Sher-Gil Archive, which Sundaram had created in 1995-6. In 2007, Sundaram exhibited his Retake series, along with his other works that drew in his aunt thematically, at the landmark exhibition “Amrita Sher-Gil” at the Haus der Kunst, Munich, and the Tate Modern, London.

The retrospective also houses a Family Room which consists of The Sher-Gil Archive (1995), an arrangement of Sundaram’s personal and family history: photographs of family members juxtaposed with other personal objects such as the handwritten letters by Amrita Sher-Gil, old ivory lace, a warped fan, a broken crystal wine glass etc. In the installations which are part of the retrospective, Sundaram traverses through the industrial landscape and discards, oil grids, things sourced from local flea markets and second-hand markets to fragile terracotta recasts of modernist-master-sculptor.

Boat Kalamkhush, handmade paper,steel,wood, video, 1994

Several of Sundaram’s recent projects involve the use of photographs, found objects, video and three-dimensional constructs in a variety of materials. Titled after one of his paintings Step Inside And You Are No Longer A Stranger (1976), the retrospective invites its viewers to engage with gesture and layered narratives, addressing memory, history and the personal archive, marking significant shifts in the history of Indian Modernism.

In this interview, Sundaram talks about the retrospective, his creative process, the art of installation and mixing his artistic practice with history, memory and archives. Excerpts from the interview:

Nawaid Anjum: Your retrospective, “Step Inside And You Are No Longer A Stranger” captures the entire course of a career spanning 50 years. It is almost a lifetime of work. In these years, your works have traversed a wide gamut of range, incorporating so many strands of influences, mediums and forms. These explorations have seen you imbue your work with a certain edge, with each of your work concealing a spectrum of meaning, drawing on several universes and, at the same time, being universes unto themselves. How do you look back at your journey of half a century?

Vivan Sundaram: Right from the beginning, there are these junctures in my work which have certain patterns which reflect a constant questioning of what I have done and what follows. So, it could be just in terms of aesthetic inputs — from kitsch to very refined pallete (66-68). And, then, as we move along, there is a period when I’m involved in painting people. In fact, I was a part of the seminal 1981 exhibition, “Place for People”, organised in Bombay and Delhi, wherein big artists like Bhupen Khakhar, Ghulam Shiekh and Sudhir Patwardhan and Jogen Chowdhury also participated. That’s the narratives of the painting that emerged in India in the ’80s. As that positions itself through the decade, I find myself wanting to interrupt that and shift to another medium. Some flashbacks: My sister is in Hamburg. When I join her, enchanted by Hamburg’s harbour and ships with a certain degree of romantic appeal, I use soft pastels — they are very rich, pure colours. Then, leap ahead two more years. I’m the unofficial guest of the Government of Poland. And I want to go to Krakow. But I was told it was not on my itinerary, but if I paid the travel person $50, he’d take me to Auschwitz. Then, there is another flashback: It’s Slade School of Fine Art in London where I was told I could choose history of art or history of cinema. I chose the history of cinema. And then it started a course on Second World War. A documentary and feature films were made on World War II. And suddenly the reels of those films came in front of me. So, suddenly, you see the reality and then you see the reality that has got embedded. And so, like that, I spontaneously go back to my hotel room, make my first drawing and call it Penal Settlement (drawings in charcoal). There is a relationship between my being topical, reacting to situations and events and then that works itself through the whole year of making more than 60 drawings. So, on the one hand, I’m quite spontaneous, there is some history embedded in my works. I excavate the history, the history of cinema.

Towards the end of the ’80s, I encountered, indirectly of course, another war. I’m in New York and the Gulf War starts. The American media pushes its own line and I’m disturbed by it and I stay over another war. Charcoal is a very good material. It has a graphic quality. But the engine oil had a strong sense of depth of structure and suited the Gulf War which was fought from the air. I have a strong sense of aerial view. Since it was a war about oil, I thought: why don’t I go to my garage? In those days, petrol had a lot of carbon in it and we used to clean our cars with it. And I got a range of engine oil with carbon in it. That created a colour and it became fluid.

Then, subsequently, at the end of the decade — it’s now 1989-1990 — I felt that India was changing and the world was changing. I then had to reconfigure what it was all about. Politically, there is a global situation in the collapse of the Soviet Union and the rise of the Right wing here which is now very much present: the demolition of Babri Masjid followed by the killings in Bombay, the riots. Again, I had to forge a relationship with the found object. And the found object here was an iconic photograph, taken by Hoshi Jal of The Times of India, of a dead man killed in the streets. I kept that folded in my wallet. I asked myself: How do I make sense of this? Somehow, living with that photograph for six months, I felt that this becomes the key by which I can start making an artwork. The artwork then named itself as a form of installation art. So, it becomes an immersive experience for the viewer. By that time, I had already started referring to Amrita Shergill’s father, Umrao Singh (1870-1954), who is acknowledged as one of the pioneers of modern Indian photography. I said I will now use the retake of photographs of Amrita and the family in the digital. Advertising people use the digital manipulation, but here there was an album which documents the family life. By inserting the relationship of the father and the daughter, there are four series which are not manipulated. They come as a strip: Umrao Singh taking self-portraits during the years with his Hungarian wife over 50-year period. So, Amrita’s exotic mother and Amrita became the main subjects for Singh’s photography. But technically they are family album pictures. I used it as a tool which allowed me to play with it, exploring the relationship between desire and sensuality lost in photographs. Amrita always wanted to be photographed. So, I play the whole thing in the series. But narrative-wise, these are family album pictures.

Nawaid Anjum: In these multiple forms and textures, one notices a semblance of coherence. The times when you started practising as an artist were worlds removed from today. Has the perception of an artist and his perceived role in the society changed over the years? Do you see more openness and acceptance of the avant-garde in contemporary art?

Vivan Sundaram: The first break that came in the course of my career was towards the end of the ’80s. There was a global change and a national change. I felt that my journey in painting, graphics and drawings had to reposition itself. The repositioning came when I wanted to connect with people in different disciplines, talking to photographers of all hues. I made a work called Stone Column Enclosing the Gaze. I was reading Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography which argued that photography had been there for 100 years but there were no “monuments” to photography. It hadn’t become the museum of eye as it is today may be The Museum of Modern Art (MOMA)? Then I met a young sculptor named Frank Benson. He suggested that I create a 6-foot-high stone column and get somebody to carve it since I was not a carver. For the rest on the curve, I foregrounded the quotation of Barthes. In front and behind are Amrita’s photographs. As you turn around, you see the photo reflected in the mirror. That’s quite a seminal work. Subsequently, I went on to explore the relationship between photography, text and sculpture. For instance, “Memorial: An Installation with Photographs and Sculpture” (1993) was my response to the December 1992 destruction of Babri Masjid in Ayodhya and the violent aftermath.

Insurrection, 1946

Nawaid Anjum: You draw on cinema a great deal. It is a powerful audio-visual medium. How did films you watched shaped your sensibility? Today, how has your relationship with the medium changed?

Vivan Sundaram: I’m a product of the ’60s movement which saw the proliferation of auteur cinema. The director was an author. There had been great people earlier, but the ’60s did produce Roberto Rossellini, Federico Fellini and Jean-Luc Godard, who is my special hero. He puts more provocative questions and takes a radical position. Spanish filmmaker Luis Bunuel, the father of cinematic surrealism, was a major influence. I was also shaped by the climate in Europe. I became very much a part of it. Cinema became a part of my expanded friend.

Nawaid Anjum: How do you look at your creative process? How do your works take birth? How do you approach, for instance, an installation? Does it all begin in the head and you move from there?

Vivan Sundaram: Different works have different strategies of entering some parts of it. I spontaneously enter the unknown. For instance, I come back to my hotel room and Auschwitz is there, and I make a tiny little drawing called Penal Settlement. So, here, one single photograph introduces my entering the space of the zone of installation art and the larger context of what’s happening at the memorial. The relationship in the documentary photograph uses a counter strategy of sculpture and a minimalist position. The influence of sculpture resurfaced in stone column works in 1992 which captured an almost aggressive reality. They owed their genesis to a painful, tragic image of a Muslim killed on the streets of Bombay. My first photograph was pasted literally with 3,600 nails. The nails from the back came in the front. So, it formed a very minimal screen. You barely see this figure since it provides a protective screen. Then, there was a series called Shelter which drew on Shakespeare’s idea of giving man a “decent burial”. That became a metaphor to deal with death and mortality, which also appears in different aspects of my work.

When I start, there are multiple things that enter the frame. Now, it’s majorly minimalism. In the ’60s, when I was in London, it was pop. Sometimes, something which is not part of your aesthetic or understanding has a way of lodging itself in your range slowly. In other works, the photographic image meets the minimalist and immersive aesthetics. So, it is about making a ground plan. And then you take risks and see what happens. Sometimes, a work becomes memorable because you took risks. I also draw on whatever sense of history I have, especially what I learnt as a student in Baroda.

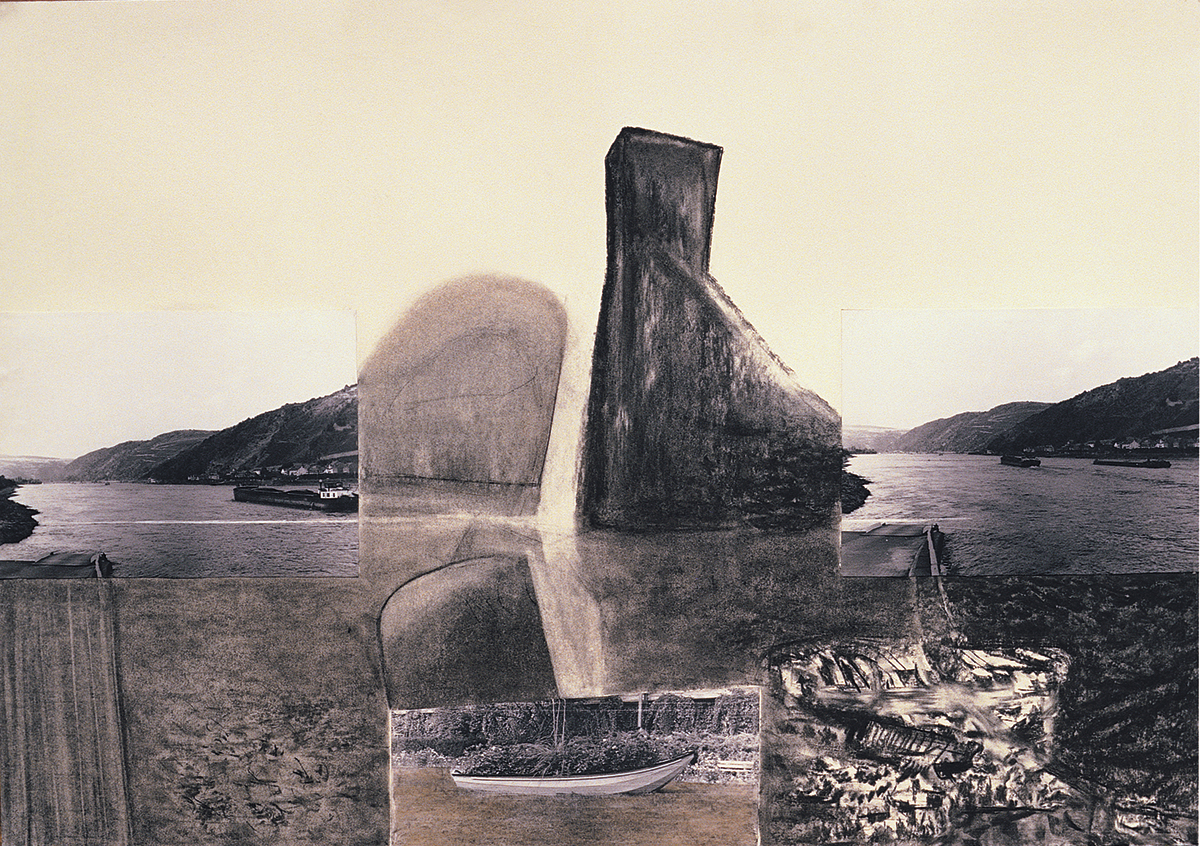

Riverscape: A River Carries Its Past, engine oil and burn marks on Kalamkhush handmade paper, oil and waterin zinc trays, 1992

Nawaid Anjum: Do themes work as your drive? Are you weighed down by the thematic content or intent of your works? Is it something that the artist should at all be preoccupied with?

Vivan Sundaram: Through the ’80s, the thematic content — the figurative narrative — was very dominant. It was seen at the 1981 exhibition “Place for People” in which I participated. The shift came in the ’90s. The series that drew on the Gulf War is all about the landscapes there. The works in the Long Night series, drawings in charcoal, have a connection with cinema. It is about concentrating on structures and metaphors. Sometimes, you create a shape or form that suggests that something more is going on which is complex and disturbing. So, there is a relationship between the subject and making meaning out of abstraction. Sometimes, there are opposite tracks. When you’re introduced to a subject matter with minimalist aesthetics, it is antithetical to the position the Americans took and Anish Kapoor followed. In fact, when Anish Kapoor saw my work in London, he asked why I put graffiti marks on my works. I said, “That’s the difference between you and me.” I like to suggest the politics through graphic signs or through text. In the ’60s, I encountered a great artist in Thailand who’s a Buddhist and a great admirer of minimalist jars who says that he has the right to put Buddhist herbs in these containers. What should the academy of the minimalists say? Will they say that it is not minimalist since he has played around it? Sometimes, if you move further away from the heart of the academy, you find greater freedom.

Shifting the Elements II, charcoal and photographs on paper, 1988

Nawaid Anjum: Some of the key words that define this retrospective are “history, archive and memory”. Are all these things interlinked? How crucial are these terms and their intermingling to you? At this stage of your career, what do you hold holy as an artist?

Vivan Sundaram: One is not thinking about their open relationship. As an artist, you juxtapose things with each other, put opposite things in a dialogue. There can be tensions but it can also become another eye. And then something starts. I propose the designer, Siddharth Chatterjee, who is also very open with the sense of artistry. So, finally, it is a collective enterprise. The other key word is the “site-specific installation”. Things may be just in fragments, but it has to be mainly an immersive experience so that a viewer gets involved and linger around. But there is greater academic interest in history and historians and there isn’t the same emotional connect among people. However, the works which are part of this retrospective will disturb and disrupt the audience.

Nawaid Anjum: Today, we have moved beyond the notion of artist as a mere painter. There is also greater acceptance and willingness on the part of the viewer. As a pioneer of installation art in India, how do you see this transition?

Vivan Sundaram: Everything takes time to be accepted. Today, the viewers are more exposed and sophisticated. Even the media relies less on the visual image. Sometimes, the visual image they use is less forceful than their articulation. In visual arts, eye is the organ, but there is also the mind. The mind produces ideas and depth which have to be constantly present. After the ’90s, things have opened up and artists have been travelling so much, exhibiting so much and also becoming famous mid-career, like FN Souza, SH Raza, Akbar Padamsee and Gulam Mohammed Sheikh.

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated