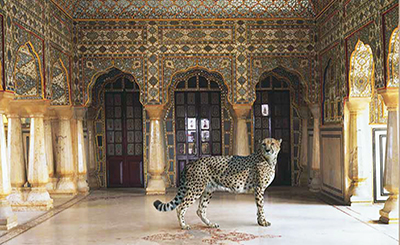

A picture from Catherine Leutenegger's 'Kodak City' series. Photos: Dhiraj Singh

Chennai Photo Biennale, in its second edition, brings to the fore many interpretations of the expanding universe of photography

“I went into photography because it seemed like the perfect vehicle for commenting on the madness of today’s existence.” — Robert Mapplethorpe

These past few years, one has been forced to ask whether it was possible any more to trust an image. We are after all living in a ‘post-truth’ world where faked and photoshopped pictures go viral all the time. Where the fake image has an almost Voldemortian power of falsifying what really is in ways that were unimaginable a few years ago. It would seem then that pictures are no more true as they once used to be but instead have become agents of moral corruption and decay. In such a scenario of willful blurring lines we get to have an event that makes you explore the increasing complexity of picture making and the faith-like relation it once had with truth and reality.

This year’s Chennai Photo Biennale, which is in its second edition, brought to the fore many interpretations of this expanding universe of photography. It was great to see the Biennale take on an air of multi-disciplinarity which was so far only seen and felt in the field of visual arts. What was also noteworthy was the use of venues that put the spotlight on Chennai’s past in very intelligent and well-thought out ways. Venues such as Senate House overlooking Marina Beach, Madras Literary Society’s 200-year-old library and the Government Museum perfectly showcased an extremely photogenic city that straddles many different Indias, all at the same time.

Vijay Jodha's work on farmer suicides

What I found particularly endearing was the idea that distantly hung over the Biennale like a cloud. And I mean it in the best possible of ways. The idea of a ‘Fauna of Mirrors’ comes from an old Chinese legend of an emperor who colonised the world that existed on the other side of the mirror. These ‘mirror people’, though earlier a friendly lot, became hostile towards humans because of the emperor’s capture and have ever since been feuding with them. The tale in itself is an allegory of human unhappiness at being shown the mirror but in the context of the Biennale, it became a deeply introspective encapsulation of what curator Pushpamala N. had in mind for a photography show of this scale. I have been a fan of Pushpamala, the artist, whose work and practice I adore because she uses impersonation as a way of exploring the contradictory nature of myths and histories in the subcontinent.

So, I was really keen to see how Pushpamala would be as a curator. And I have to say that the Biennale remains true to its idea of holding a mirror to the changing face of the planet in a host of aspects that include environment, politics, gender and history. I found Archana Hande’s work extremely thoughtful as it dissolved many binaries not just of image-making but also of looking at the colonial enterprise. Titled “The Golden Feral Trail”, it sought to reimagine the exploitative tale of the Indian camel that was shipped to Australia to work in the mines there. Set in a projection pit strewn with crystals, the work involved moving animations of camels, trains, drilling equipment snaking through the Australian outback in a bid to extract gold.

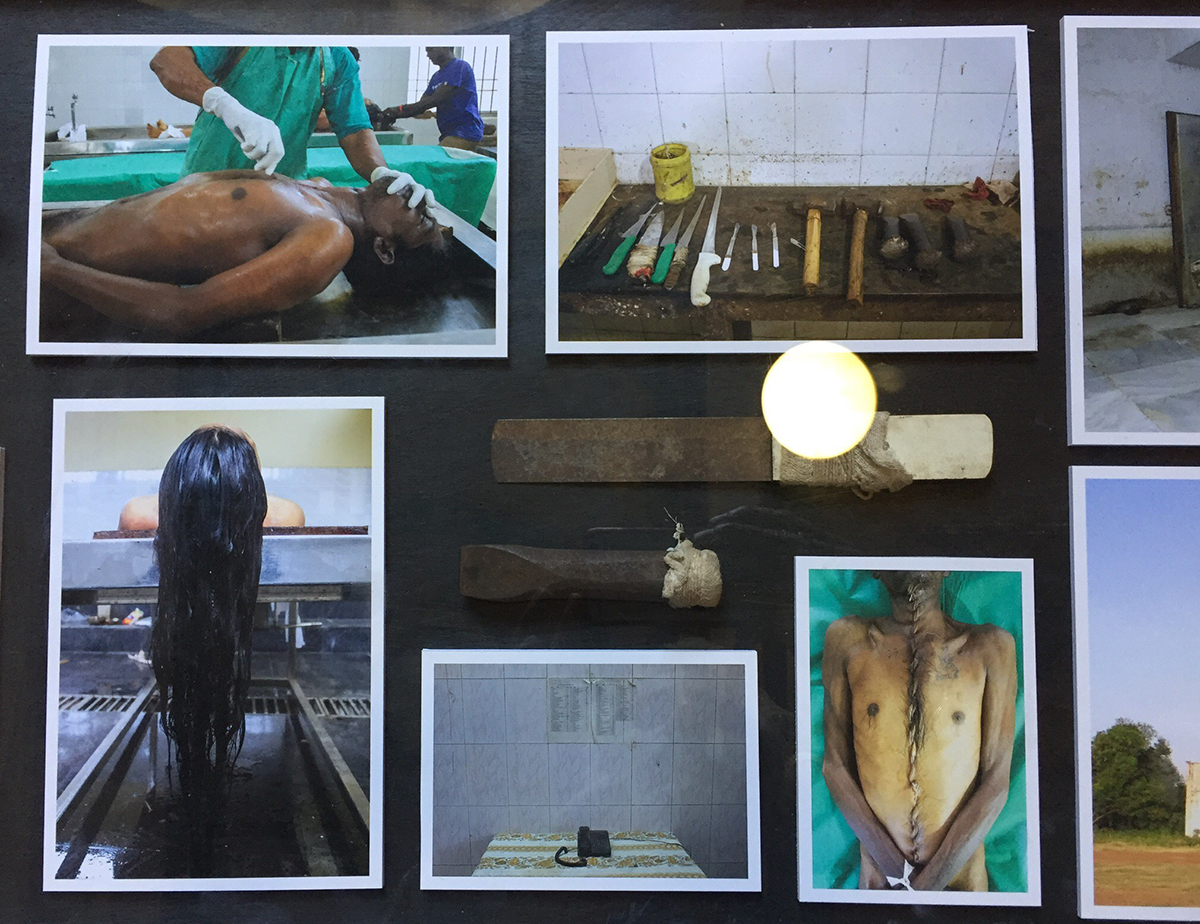

Arun Vijai Mathavan’s installation on autopsy workers

Manit Sriwanchipoom from Thailand, too, furrowed deep into the trauma of his country’s past, 1976 to be exact, when student protests were violently quelled by the ruling military junta. The most well-known of these was the Thammasat University massacre where protesting students were lynched, shot and raped under the watch of the military. The death toll in the massacre is still disputed though official figures are said to be a fraction of the actual numbers. Manit, in his works, has inserted a ‘pink man’ in some of the massacre’s most iconic (and gruesome) pictures creating images that, at once, evoke both humour and horror. “My series reflects how the authority or the ruling government is trying to hide information from the public,” says Manit. “If they can control the narrative, it means that they control the power; that is why most governments don’t want the real truth to be exposed,” he adds. But Manit doesn’t simply put these pictures back in circulation. He inserts in them his own ‘representative’ of collective greed and bloodlust by putting in his mocking ‘pink man’ in them. “I want to make them look like they are people we should ridicule, make fun of. This is the power of humour; you can play with the authoritarian government,” he says.

On the other hand, Vijay Jodha’s pictures are of family members of Indian farmers who have committed suicide. Mounted as larger-than-life portraits, these pictures are devoid of any action or drama but the story implicit in them is worth the effort. “When you go out to shoot the celebrities, film stars and other powerful people, you make sure you shoot them very cleanly. The details are there, you know the skin tone, the texture of their clothes, and everything comes out well,” Jodha says. “But when you shoot people like these or riot victims, then you just put them in a bunch, not bothering to get details. When I was doing this project, the idea was to restore individuality to them,” he adds. Also on display are Magsaysay award-winning journalist P. Sainath’s photos that are distilled from his vast corpus of work on rural India. In these pictures, Sainath captures the plight of rural women whose daily toil goes largely unrecognised due to gender discrimination.

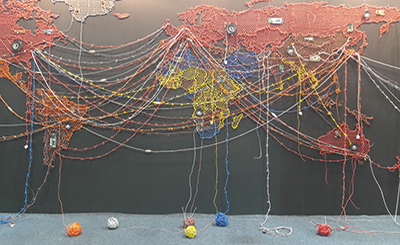

Inside view of Senate Hall showing Atul Bhalla's work on fishing communities of Tamil Nadu

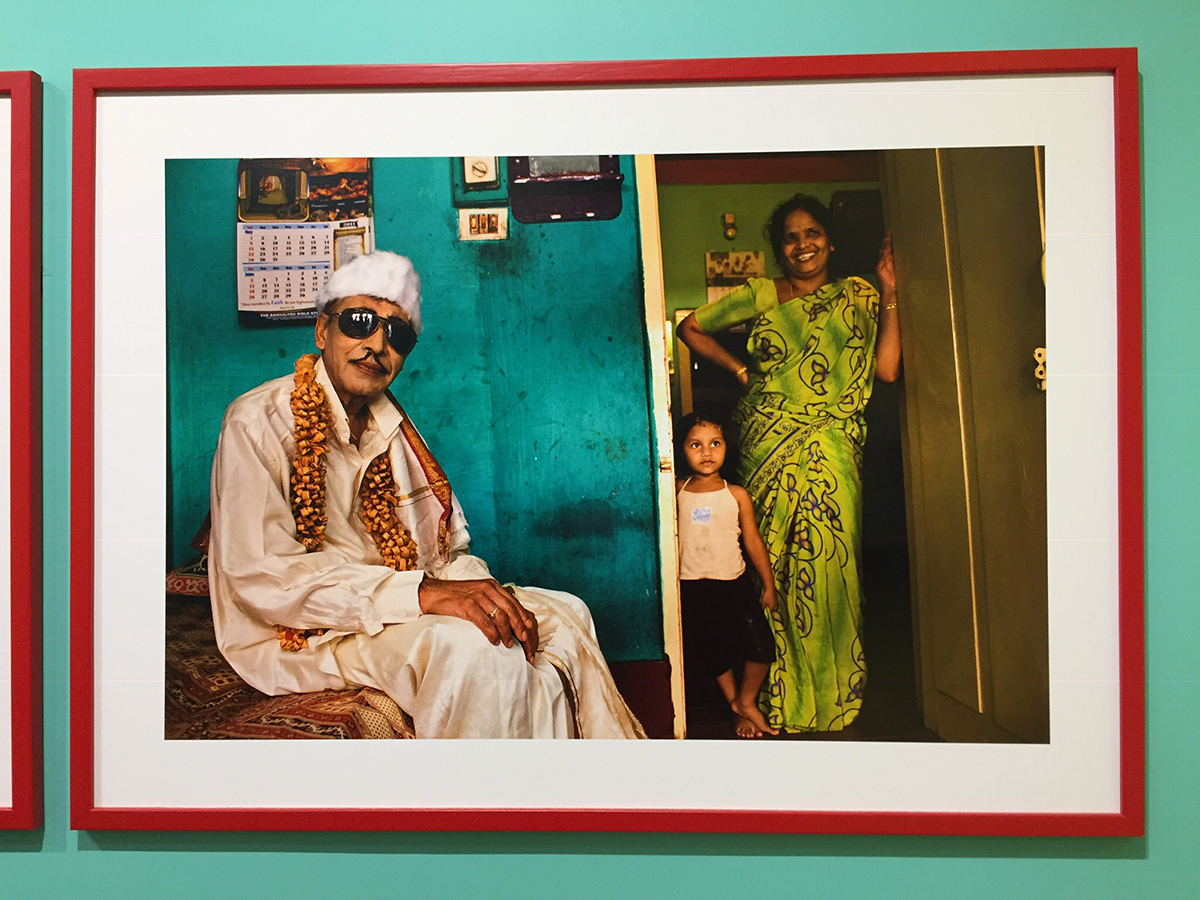

Indu Antony takes on the issue of gender in a more personal way, picking out the aspect of women behaving as men as she photographs herself dressed up as Superman, Captain Jack Sparrow, a coconut seller, a police inspector: all archetypes of stud masculinity. But even as she indulges in this roleplay, one isn’t allowed to forget that her underlying message is seriously concerned about the freedom that’s often denied to women in male-dominated public spaces. Cop Shiva, a former traffic cop-turned-photographer, has taken to documenting the lives of impersonators. At the Biennale, he presents a series of pictures of an MGR impersonator. “The man lived like MG Ramachandran everyday for almost 47 years,” says Cop Shiva. “For me, he was a common man who lived an extraordinary life.”

Arun Vijai Mathavan focuses his lens on autopsy workers in Indian hospitals. These aren’t doctors but “sanitary workers” often belonging to the Dalit castes who cut and stitch corpses, before and after the medical staffers make their report. Mathavan’s pictures capture the grisly anatomy of the post-mortem ritual. It is a sight one is not familiar with, but Mathavan goes where no other Indian photographer has dared to go before.

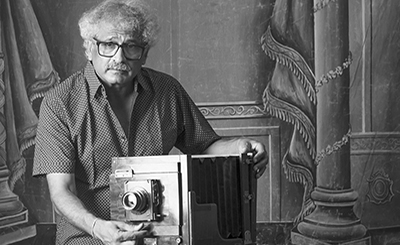

Cop Shiva’s documentation of an MGR impersonator

Catherine Leutenegger takes you to an American suburb, which remained a household name for much of the 20th century. Her series, “Kodak City”, chronicles the wiping out of a film manufacturing base set up by George Eastman himself. When Kodak filed for bankruptcy in 2012, many of its office buildings were razed to the ground. Catharine has made their videos part of her work, mostly comprising pictures of Kodak buildings in Rochester, New York. The images are mostly unpeopled but they are still a moving study of loss and decay unleashed upon a mascot city by the arrival of digital photography.

Angela Grauerholz showcases another form of loss and decay in her works “Privation” and “The Empty Shelf”. Taking the form of two giant photo books, Angela creates a documentary of disappearance. “Privation” is a more personal work that has scanned images of books from her library that was burned down in an accidental fire. “I realised that the books were very beautiful after they burnt,” she says, “I’ve been thinking a lot of what is the future of books and how can I sort of participate in the photographic reflection of that. Also, the future of the materiality of photography,” she says. Exhibited at the rundown Madras Literary Society library, that incidentally owns one of the first printed editions of Aristotle’s Opera Omnia and Newton’s Principia Mathematica, Angela’s works take on a larger context of the function of books in an increasingly digitally stored world.

This year, the Chennai Photo Biennale spread its wings to some unorthodox venues. These included railway stations, such as Chintadripet, where student works hung around escalators and landings. I thought this was a wonderful way of engaging a moving population of daily commuters who would otherwise not come to a gallery or any other formal viewing space. Displayed at Chintadripet railway station were works by the students of Srishti Institute of Design and Technology. iPhone pictures by students are also displayed in the open at the Government Museum. Pushpamala’s own video art is shown at Phoenix Market City mall. This certainly helps open up the conversation about photography among the masses.

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated