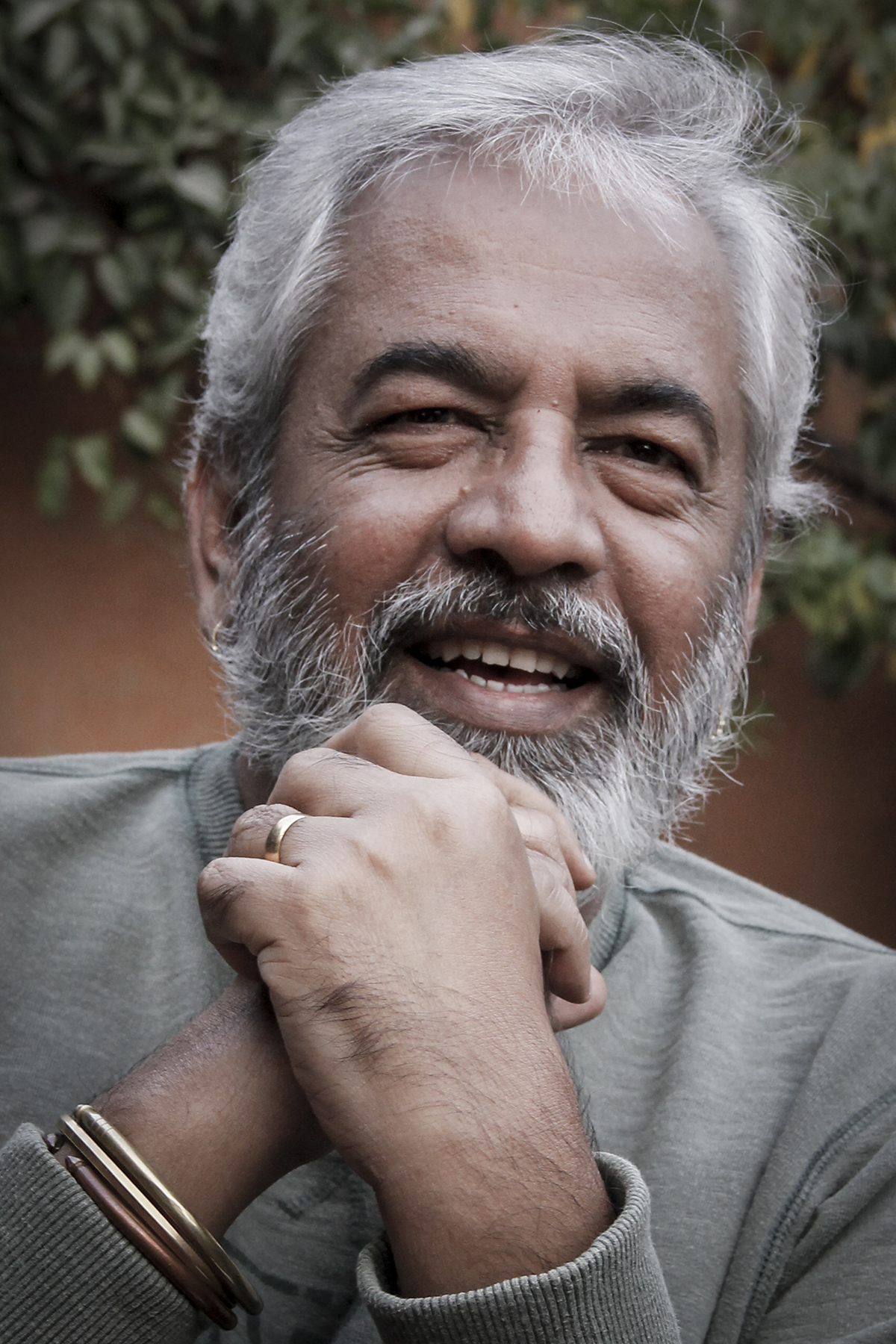

Dinesh Khanna in New Delhi recently. Photo: The Punch

To Dinesh Khanna, photography is

an extension of his very being. He observes, therefore, he is. His observations

bestow upon him the ability to process it in his work, sometimes consciously,

but often unconsciously. Khanna, co-founder of the Delhi Photo Festival, has

been involved in creating images for advertising, editorial and corporate

clients, specifically in the area of food, still-life, people and interiors for

over two-and-a-half-decades. He uses his medium to “share my aesthetics as well

as express my concerns”.

Most of his photography, Khanna says, happens instinctively. “You are blessed if you are born with visual talent, but over the years, you also collect a lot of experiences and also observe what is interesting in terms of angles, compositions, light ...how light works on certain things...how expressions on human faces work...how people interact with each other...I usually tell my students: Don’t shoot all the time, but watch all the time.These observations get stored in that hard disc also called the brain, where you are not consciously referring to it every time you’re shooting, but sub-consciously your mind is making those connections,” says Khanna, who curated the photography programme at the Serendipity Arts Festival (SAF), held in Panjim, between December 15-22, 2017.

The second edition of SAF saw Khanna introduce us to the archival and contemporary photographic practices. The objective of the programming, according to the festival brochure, was to focus on the “inter-disciplinarity in photography, with projects addressing a myriad of topics ranging from environmentalism to the history of Indian jazz”. As the discipline curator, Khanna designed Nature Untamed: An Exhibition of Africa’s Wildlife, as captured by Anup Shah and A Slow Violence: Stories from the Largest River Basin in the World, which focused on stories of personal and ecological loss from the Ganga-Brahamputra basin — the largest river basin in the world. The latter, a photographic installation, distilled the images shot by Arati Kumar Rao over the past three years at the basin.

“I do believe that art — and that

includes photography too— has somehow been trapped into believing that good art

can only be art which is socially conscious. Good art is only that which would

want to save and change the world. A good artist is only someone who is

socially responsible. I think that is too restrictive a definition and traps art

in a very singular space,” says Khanna. Excerpts

from an interview:

Nawaid Anjum: Let’s start with Reciprocation, your last show with Kathryn

Myers. How did it come about?

Dinesh Khanna: When I met Kathryn Myers, a Fullbright scholar who is also an Arts Professor in the USA, she was doing a project on Indian artists and she had seen my column called ‘Double Take’ in the First City magazine. Whenever Kathryn came to India, she used to refer to the First City magazine as it covered the art and culture scene in great detail. She got in touch and wanted to interview me for her project, ‘Regarding India”and discuss my work as a photographer. After that, we kept in touch. Both of us have an interest in Varanasi and that's actually where we met first. She did my interview for her website in Varanasi. Through Nazar Foundation, we organise “Nazar ka Adda”, every two-three months in which we invite people to talk about their work. Kathryn was one of the photographers we’d invited to talk. We noticed that there was an interesting similarity but also a difference in the way we saw the same subject: Varanasi. Both of us look at colour, but being a painter, her vision is somewhat different from mine. That’s how ‘Reciprocation’ came about. It is interesting to work with another photographer and juxtapose your work against his/her works. I have done that once earlier. That’s actually how Nazar Foundation came into being; Prashant Panjiar is my Co-Trustee in Nazar Foundation. He and I did a two-photographer exhibition with Palette Art Gallery called ‘Tirtha’ about 6-7 years ago. Prashant had done a lot of work on the Kumbh Mela in Black & White and I have done a lot of work on spirituality and faith. I’ve done a book on spirituality too, called “Living Faith.” The show, “Tirtha”, juxtaposed Prashant’s B&W photojournalistic works of the Kumbh and mine from the Faith series. It was, again, a conversation between two photographers in which we talked about the same thing but from a different viewpoint.

Dinesh Khanna. Photo courtesy of Dinesh Khanna

I think that’s what makes art of any kind, whether photography or dance or music richer because when you are able to actually accept and enjoy another point of view and give it enough space in your own mind as an alternative way of looking at an object or situation, it ends up enriching you. It’s something that’s true of democracy and politics too. The problem with India these days is that people are not ready to agree with another’s point of view. One has got to at least listen to the other person. So, in photography or art or politics, one must be willing to open one’s mind enough to listen and then reciprocate and have a conversation. Instead of becoming antagonistic, one should try to find a meeting point between the two ways of seeing.

Nawaid Anjum: This quest to find the meeting grounds and have a

conversation with another artist springs from a deep well of experience and

understanding of your craft. Let’s talk about how you ended up as a

photographer. Your body of work is marked by a certain richness of expression and

is also rooted in our core ethos. In some sense, your photographs are a

celebration of a way of life, of a way of seeing. Tell us about your journey

and how has it been shaped?

Dinesh Khanna:The interesting thing is that both the points you are making — about what inspired me to be a photographer and the fact that I seem to be rooted in India — actually the opposite is true. I decided to look at things this way by deciding not to be a photographer. I decided to shoot India as an outsider because I felt I was an outsider. I live in Delhi and I used to work in advertising. But I realised that I actually knew verylittle of this vast country which was mine.I didn’t know much about large parts and aspects of India. So, I used photography to discover my country.

I didn’t want to be a photographer because my father was a photographer. He used to work with the American Embassy and used to be with SPAN magazine. I learnt my basics from him. While I was in school and college, I had access to a camera, to film. We had a dark room at home. My father used to encourage me to shoot and even to travel with the camera. So I used to go to places like Rishikesh and Haridwar to shoot. And this way I got into street photography and started loving it. However, when I was finishing college, I was very clear that I would not be a photographer. Though this had nothing to do with photography and my love for the medium. I thought that in India, due to the caste system, if someone’s father is a cobbler, the son becomes a cobbler. If the father is a tailor, the son has to become a tailor. The son is expected to take the family business or legacy forward. I think this is something that is fundamentally wrong with our social system. The caste system is still there and people still live according to its diktats. So, at the age of 19-20, I had told myself that I would not be a victim of this. Though it had nothing to do with how much I loved photography. Of course, I loved photography. The thing is thatI was not a very good student. Nor I was interested in studies. But I had gone to a very good college and well-known school. And that is another problem in our country: If you get the right labels in India and you are fluent in English, then it’sall okay. And this definitely worked for me. I feel that there is so much wrong that had been happening in India in terms of social and cultural discrimination. We must start breaking down the barriers and divisions. If we don't work on this, India will continue to be what it is and not be able to make our society more fair and equal.

Anyway, I drifted into advertising after college, in spite of my rather poor grades, and ended up spending 11 years in the business. And I must say, I really enjoyed the profession. Also, fortunately for me, I did really well. I worked in agencies like Clarion, Lintas and Enterprise. In my last advertising job at the rather young age of 28, I became the branch director of Enterprise. I started the agency’s branch in Delhi and ran it for five years. But, somewhere along the line, I realised that photography was my first love and I wanted to pursue it professionally. So, after about 10-11 years of advertising, I decided to be a photographer. In 1990, I quit advertising and took up photography as my profession. I started doing small assignments — product and people photography because I had to teach myself on the job as I had no training or experience at all. After a-year-and-a-half of doing small commercial assignments, I felt that the reason I wanted to be a photographer was not only to make a living and, even if it was to make a living, I did not want to just do advertising photography. For me, photography has been a means of expression, a way of looking at the world, of discovering what I am passionate about. I was also conscious of the fact that I was a typical metro kind of person and knew very little of how the rest of India, outside of cities like Delhi and Bombay lived their lives. And I wanted to discover this ‘Other India’ for myself. And the way I wanted to do that was through traveling and using photography as my means of ‘seeing. ’So, since I had a sense of what interested me, that’s what I started doing. I continued doing my commercial work, but whenever I had the money and time, I used to visit places like Pushkar, Benaras, Hyderabad, Kanchipuram and so many others. Whenever I would hear about a mela or a festival or anything interesting taking place in a city, I’d travel to that city, whether by road, train or air.

Through the 1990s, I travelled a lot and shot a lot. All over the country. Small villages, medium-sized towns and large cities. Melas, festivals and bazaars. Mosques and mandirs and gurdwaras and monasteries. I was interested in exploring and photographing all of them. But all this was without any particular project or subject in mind. I was totally fascinated by everything I saw through my camera and in love with all the new and wonderful discoveries I was making about my own country. The colour, the textures, the people, the architecture, the festivities all attracted me, but amidst all this it was the individual and her relationship with her milieu and surroundings which I tried to capture as a photographer. I had my first solo exhibition in 1996 in Mumbai. Then, in Delhi, in 1997. I never thought I was ready for a solo, but Prabuddha Dasgupta, who was not just a friend but also my mentor, insisted that I did a solo show at NCPA Mumbai’s Piramal Art Gallery. He spoke to the NCPA and they saw my work and agreed to the show. Interestingly, Prabuddha was part of the creative team that I worked with as part of Enterprise. While I was the branch director at Enterprise, he and Akash Das, (who is also a fashion photographer now), the art director, were the agency’s creative team. We were very good friends. My wife, Rachana, was also in advertising and worked with them in Everest earlier. We were like one large, happy family.

It so happened that David Davidar, the then MD of Penguin India, visited my show in IIC and asked me if I would be interested in doing a coffee table book. I, obviously, was ecstatic by his offer.When we were discussing the subject, I told him that I had been travelling for 10 years and would go back and look at my archives to see what I could put together for the book. It was then that I realised that what I had been doing instinctively was shooting the traditional bazaars of India and the myriad shades of its faith.The reason for it is that I was so fascinated by the other India that I wanted to explore and discover it. And that’s what I had been doing with my camera during that decade of regular travel. India is very open and always has been. Our commerce is in the open and our faith is also practiced out in the open. Temples are in the street corners, people pray, offer namaz or have gurudwara’s langar in public places. There is no constraint. So,I went back to David and told him about these 2 themes, about the Bazaar and Faith, I had unconsciously been shooting and following with my personal photographic exploration. Fortunately he and Bena Sareen, the chief designer, thought that both the ideas were very interesting and they would like to do 2 books and not just one! And so ‘Bazaar’ was published by Penguin in 2001 and ‘Living Faith’ in 2004.

Photos by Dinesh Khanna, Varanasi

During the analog period, photography was a somewhat restricted medium. Opportunities were few and only the rich or the professionals could afford to indulge themselves. However, since the time it went digital, it’s been much easier, and cheaper, to shoot photos.To my mind, the Internet and the ease to share photos and reach thousands of people is as significant a difference that has come to photography as the ease of takingphotographs with digital cameras. The photographic film was a very tough taskmaster; one needed to understand the chemistry and physics of photographyand, additionally, be sensitive to the moods of light.So, one was forced to learn photography as a craft,and while you did so, you also sharpened your vision.With digital, that unfortunately is not quite the case.With film, it took us a few years to work on a project, both because film was expensive to use and difficult to master. And the opportunities to share your work were severely limited as one could only share physical prints with a limited number of people. But now things are different. Now, even a DSLR has a Wi-Fi and you can very easily and quickly post andshare your images on social media. And if one is not careful, and inspired, digital can make one visually lazy as there is very little rigour required to learn the craft. Or so it would seem. Social media has, seemingly, given us the power to ‘publish’ our work and share it with the world without any constraints. Or restraint. I am very active on Facebook and Instagram myself. But more to inform, share and strike up conversations about photos and photography and not with the misconceived perception that my work is published. Today, curiously, too many people think that they are a photographer simply because they own a camera. It’s like saying that everyone who has a pen is a writer.

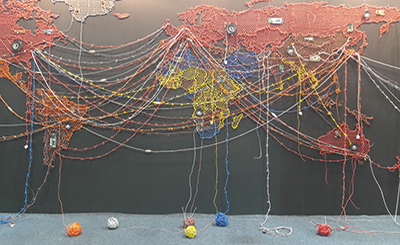

The second edition of Serendipity Arts Festival, held in Panjim in December 2017, saw Dinesh Khanna curate Nature Untamed: An Exhibition of Africa’s Wildlife (above), as captured by Anup Shah and A Slow Violence: Stories from the Largest River Basin in the World, which focused on stories of personal and ecological loss from the Ganga-Brahamputra basin — the largest river basin in the world.

However, there is a lot more to photography

than just pointing a camera and shooting a bunch of pictures. Today, it is

true, that your camera and software can ensure that almost every photo taken is

a competent one. You do not really need to learn the craft with the same rigour

as one did with film. But to be a photographer one must be born with the ‘eye’

and visual sensitivity. It’s a natural gift that only some of us have. But that

is only the start. Much like the natural ability to sing or dance or draw. Only

some of us are gifted with these talents. But these need polishing. One might

be born with the eye for the visual, but it needs to be honed and sharpened and

evolved. One has to do ‘riyaaz’ (rigorous practice) regularly and constantly to

develop ones photography and truly excel in it. Anyone who is really interested

in pursuing photography has to be sensitive to this point or else run the

danger of drowning in the tsunami of images that we are inundated with across

mainline and social media on a daily basis. Which, incidentally, is a big

reason why most people can’t seem to distinguish between fantastic photographs

and the mundane stuff.

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

.jpg)

.jpg)