Stephen Apkon, co-director of Disturbing the Peace. Photo: Twitter

Stephen Apkon, co-director of Disturbing the Peace, on one of the most impressive documentaries of recent times that plumbs the depths of identity, transformation, and the challenges of integration

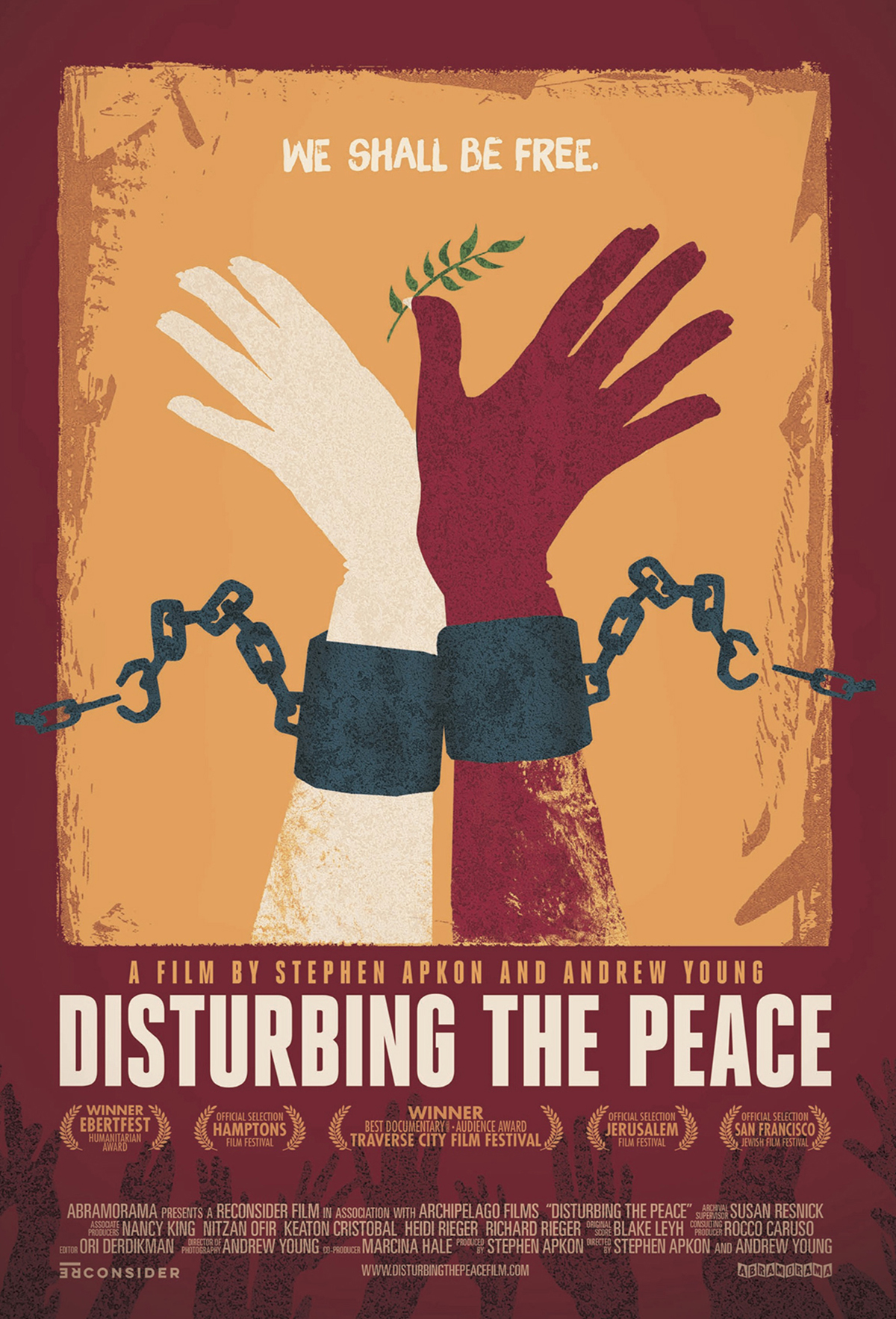

Disturbing the Peace (2016) is one of the most impressive documentaries of recent times for it plumbs the depths of identity, transformation, and the challenges of integration. It does so through the stunning stories of four Palestinians and four Israeli women and men who lived crucial moments of transformations. They belong to the “Combatants for Peace,” an association based on the principles of non-violence, formed by former military or paramilitary people from Israel and Palestine, who work “towards a two state solution in the 1967 borders, or any other mutually agreed upon solution that will allow both Israelis and Palestinians to live in freedom, security, democracy and dignity in their homeland”. To acknowledge the otherness within is more difficult than to label the otherness outside because it changes one’s life. It is a matter of challenging the individual and societal narratives, and of integrating the shadow — to quote Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung. Therefore, this cinematic journey goes far beyond being a documentary solely about the Israeli-Palestinian question.

Stephen Apkon, co-director of Disturbing the Peace, together with Andrew Young, is the founder of the Jacob Burns Film Center, a non-profit film and education organization located in Pleasantville, N.Y. that has developed educational programs focused on 21st century literacy. Apkon also serves on the boards of The World Cinema Foundation and Advancing Human Rights and focuses on other non-profit initiatives. He has presided over several productions and, with Marcina Hale, is the executive producer of Louie Schwartzberg’s more recent documentary Fantastic Fungi (2019). Along with Hale, who is a licensed marriage and family therapist, Apkon serves as the Executive Director of Reconsider, an organization that works towards improving awareness and responsibility within human relations and political dynamics.

This conversation took place at the Human Rights Film Festival Zurich (HRFF). I wish to thank Stephen Apkon, Sascha Bleuler, director of the HRFF, and Brett McClaim, for her collaboration in editing the text of this interview.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: Disturbing the Peace starts with a sentence by Joseph Campbell and ends with a sentence by Martin Luther King. What drew you to make this film and how did the audience react?

Stephen Apkon: The film was not made for Combatants for Peace, but it’s about them. And people experience the film in a variety of ways. I think most have an emotional experience, but on different levels. Some feel that it is about Israel and Palestine in a political context, framed in a historical narrative: for them, it essentially concerns geopolitics. Others feel that it is about the transformation from violence to nonviolence. There are people who have watched the film several times and they said that they use it as a meditation tool. For still others, it is about transcending duality, and I think that in Jungian terms, it is very much about integration.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: People, both from Palestine and Israel, ex-combatants or soldiers, discover their deep commonalities, their equal humanity in the documentary. There are impressive scenes that underline this.

Stephen Apkon: Yes, and not only that, they recognize that they were willing to kill people that they didn’t know. For instance, Shifa al Qudsi, who was hours away from detonating herself as a suicide bomber, was arrested and, while in prison, she had an experience with a guard who lost a brother to violence and she started to reflect on her standpoint. And to understand something of the humanity that is quite different than what she had internalized. Consequently, she realized that both Palestinians and Israelis carry the same message — the desire for peace. So the integration has really brought the shadow to light.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: There is the scene where the mother of a Palestinian combatant, Jamil Qassas, cries for Israeli victims because, she says, “blood is blood”. This episode transformed him because “in that moment, he said, “I recognized that the pain of a mother does not have any party.”

Stephen Apkon: The transformation is not a linear process; we are constantly faced with opportunities to break those patterns, and every time we think we are through, to the other side, there is something more. Yet there are not only huge moments that create transformation. They can be a shock, a very deep experience of trauma, but they can be very subtle. That’s what has happened, for example, to Chen Alon who, as an Israeli soldier manning a checkpoint, was stopping a car with a Palestinian driver with six children, who needed to go to the hospital in Israel, and at the same time, he was getting a phone call, trying to deal with his wife on the matter of picking up their daughter from school. The Israeli soldier, all of a sudden, felt something extremely wrong about being in that situation. Looking at the children in the car, he says, “I realized that there is a split there between me as a father, responsible and worried for my daughter, and me as a soldier,” because those children “are exactly in the same situation, as they need responsible adults that take care of them”. This moment creates a split, and this split is the difference between our actions and who we know ourselves to be. So, for Chen, as also for Shifa and for Jamil, whose experience was very powerful, probably one of the most powerful in the film, a split happened. And when those splits happen, as we say at Reconsider, once you know, you can’t not know. This is a notion taught by my partner in work and life, Marcina Hale, as are a lot of the concepts embedded in the film and that you see in the transformation of the characters are, with their experiences. These ideas run very much parallel to the kind of work she has done for decades, besides her psychotherapy work, and transformational workshops, which are now at the core of Reconsider, our nonprofit organization focused on shifting consciousness. The work we develop in our seminars is in the same vein and the direction of that is embedded in the film. Once you have these kinds of experiences, you can’t go back into the narrative without at least an awareness of your participation in it.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: You can’t go back in the former narrative, in which you were used being embedded and even captured.

Stephen Apkon: Yes, so here is the issue. If you look at each of their moments of transformation, whether big or small, essentially what happens, is that you get thrown far enough outside of your reality, that you recognize that you are playing a role in someone’s else story. It does not mean that you can’t go back into it, but you can’t go back into the same way because you understand the narrative — you understand the story, and the role that you play in it. And you begin to take responsibility for that. Because you have a split between the role that you have been playing within this narrative, that is a created reality, and who you are as a human being. Somebody else has written a story in which here are your enemies; here is the way to become a hero, here are your friends, here are the values you hold, we hold, that you belong to, and if you don’t hold that, then you won’t belong. There will be pain involved in not belonging. And that’s how we maintain these narratives, and how systems and institutions maintain their narratives. In fact, on a very primary level, this film is not about Israel and Palestine in the classical sense, but is also a metaphor, for all of us, in our own lives. I always say that we wake up in the morning, and we know who the heroes of our story are. We are just trying to figure out who the villain is. We also know we are the victims, and we try to figure out who the perpetrator is. It is the fusion of both of these things that keeps us stuck in the patterns that continue to recreate themselves. The culture and the institutions that we have created are living beings inasmuch as we are, and they want to sustain, to perpetuate themselves. There are languages, there are rules, and there is pain in leaving — whether it is for military, a family, or particular communities. So, in some way, it’s about the heroes’ journey according to Joseph Campbell, it’s about giving birth to oneself, and it is also the Jungian idea of psychic development — and that is really what we are doing.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: Jung’s idea of individuation deals with the dynamic processing of the complexities, and the opposites.

Stephen Apkon: Yes, and the opposites always call for the integration because if you repress or deny the shadow, then you’re always in relationship to it. It’s always there; it always finds its way. When you integrate it, you accept it, you recognize it, you bring it in, with your compassion for it — that creates wholeness. But it also allows us to recognize that we are constantly making a choice, of how we want to show up in each moment.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: You say that the film shows the asymmetry between the oppressor and the oppressed, but it also highlights the asymmetry of the common human nature. Obviously, it is harder to recognize or work out the second kind of asymmetry, than to recognize it…

Stephen Apkon: Well, because we don’t want to do it. We want to hold on to our victimhood. Both sides want to hold on to their victimhood and the cycle is perpetuated. In some ways, both societies are post-traumatic societies. You know, coming out from the Holocaust, and coming out from Nakba... I’m not equating the two; I’m just saying that you can recognize the sense of victimhood in both societies. Sulaiman Khatib, who is in the film, grew up in Palestine, and served ten-and-a-half years in prison, from the age of 14; he is the person I asked at the beginning of this process, “what are you guys really trying to do?”. He said, “We are breaking the circle of violence by breaking our own sense of victimhood.”

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: Sulaiman says, “God does not change what’s in a person’s heart until he changes it himself. The change begins with one person, and then this positive energy affects others.” This sounds very Jungian, and also reminds me of the Hasidim’s belief system — especially in Martin Buber’s understanding — according to which God essentially needs human being’s help for His work. This idea appears at the beginning of the film.

Stephen Apkon: Yes, because this really fits with the concepts that Marcina and I want to explore in our work at Reconsider. So, Sulaiman is constantly talking about not allowing Palestinians to stay in a place of victimhood. What is important about it is that he not only understands that this is the way out, but also he realizes the cycle of violence and perpetrator-victim — it almost does not matter what role you are playing; in some ways, it is easier to be the victim, and much more difficult to be the perpetrator on a soul level. Differently, if you stay within that process, your sense of victimhood would ultimately turn into the perpetrator: the cycle will just continue… So, for instance, I think there is no question, that is easy to see that Jews have a moral,… I don’t want to say authority, but holding a place of a moral potential, if you will, coming out of the Holocaust. Consequently, the notion of “never again”; and “never again” means never again for anybody. Again, I’m not comparing — that is very important — the Holocaust to the Occupation, but the sense of oppression, of being oppressed, to becoming the oppressor. Because of these very small incremental decisions, based on fear (our security demands it, “look at all that we have been through”, “never again”), yet, fifty years later, you find yourself occupying three and half million people, which is not at the core of what Judaism is.

By the way, the oppressors are always afraid of breaking the sense of victimhood, because they understand the process as well. That is why it is very hard to give up being the oppressor because you understand what you have done to oppress somebody, and the fear that the cycle continues, and that they’ll become the oppressors in turn. So both have to walk away from that sense of victimhood, together. There is a fear that Israelis experience that. Part of that fear is resolved in the decision that they make in occupying other people.

Shifa al Qudsi. Photo courtesy: timesofisrael.com

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: One could see here an enantiodromic process to recall another an expression dear to Jung... [Enantiodromia is a Heraclitus’ philosophical concept, literally “run to the opposite”, taken up by Jung and defined f. i. as “"the emergence of the unconscious opposite in the course of time”].

Stephen Apkon: Another thing Marcine and I talk about at Reconsider is the notion of micro and macro. Whatever is happening out there is happening in here. So that the battle is the battle that happens within us. And, again, that comes back to the integration: the integration of the shadow and the light, our capacity for compassion, and our capacity for violence… A thousand years ago, the Rabbis talked in the Mishnah about our evil inclinations, and our good inclinations… What they recognize is that both are necessary. You know, our sex drive, our desire to conquer… whatever it is that motivates us to actually create in this life; equally, there is our desire for peace, love, and compassion, and the integration of all these things in a healthy way, and to recognize them, not repress them. So, that notion is also very interesting to me, because wholeness in Hebrew would be Shlemut… The three letters from Shlemut derive from Shalem, and are also the same as Shalom, which is peace (שָׁלוֹם ): So peace, in essence, is not just about peace, love and compassion. Peace is integration.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: Literally.

Stephen Apkon: Literally wholeness. And that integration, within oneself, and also seeing somebody else as fully integrated, recognizing their light and their shadow and seeing all of that, and connecting in that way, does not only re-humanize others, but also re-humanize us: what we are actually doing is reconnecting to our humanity. So what we see in somebody else is what we see in ourselves. As Chen Alon said: “You can’t continue to do the work that you do within the military without de-humanizing the others”. You suddenly see them as human beings with hopes and dreams… And you start to understand this notion, this contextual notion which Abraham Lincoln expressed in the civil war: “If you were born where they were born, if you were taught what they have been taught, you would believe what they believe”. Ehud Barak, prime minister of Israel, said that if he were born five kilometers away, he would be a fighter, a Palestinian fighter, he would do what they are doing.

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: Specularly, the film portraits some Palestinian prisoners who were moved by watching Steven Spielberg’s movie Schinder’s List and who became interested in Israel’s history.

Stephen Apkon: In fact, this film is partly motivated because many years ago I was reading a magazine article written during the troubles in the Northern Ireland. It was about school children who were going to school every day, walking down streets of terror, and they would get to the school, and on a poster on the inside of the front door was written: “if you were born where they were born, if you were taught what they have been taught, you would believe what they believe”. So the narratives start well before we’re in the womb — If you think about epigenetics, or whatever else… Avner Wishnitzer — a brilliant, amazing philosopher — is the tall, thin Israeli commando who belongs to the elite units: he becomes a soldier and his father is very proud of him. Interestingly, he has said that if you grow up in a society that mythologizes the hero, you have to constantly create a villain because in Hollywood terms you can’t be a hero without defeating a villain. You know, the batman needs the joker otherwise he’s just hanging out in the mansion, has nothing to do, and never puts the cape on. So, the joker plays a very important role; he is the shadow, so we have to constantly create that in order to overcome it. Similarly, I think we can say that if you apply it to the notion of victimization, and if you grow up in a society that mythologizes the victim, you constantly create the perpetrator, otherwise you can’t be the victim…

Giovanni V.R. Sorge: This happens when the shadow continues to be projected onto the others.

Stephen Apkon: Exactly. And the only way out, is the integration. What I would say is that the only way out is the way in.

Page

Donate Now

More from Culture

Comments

*Comments will be moderated