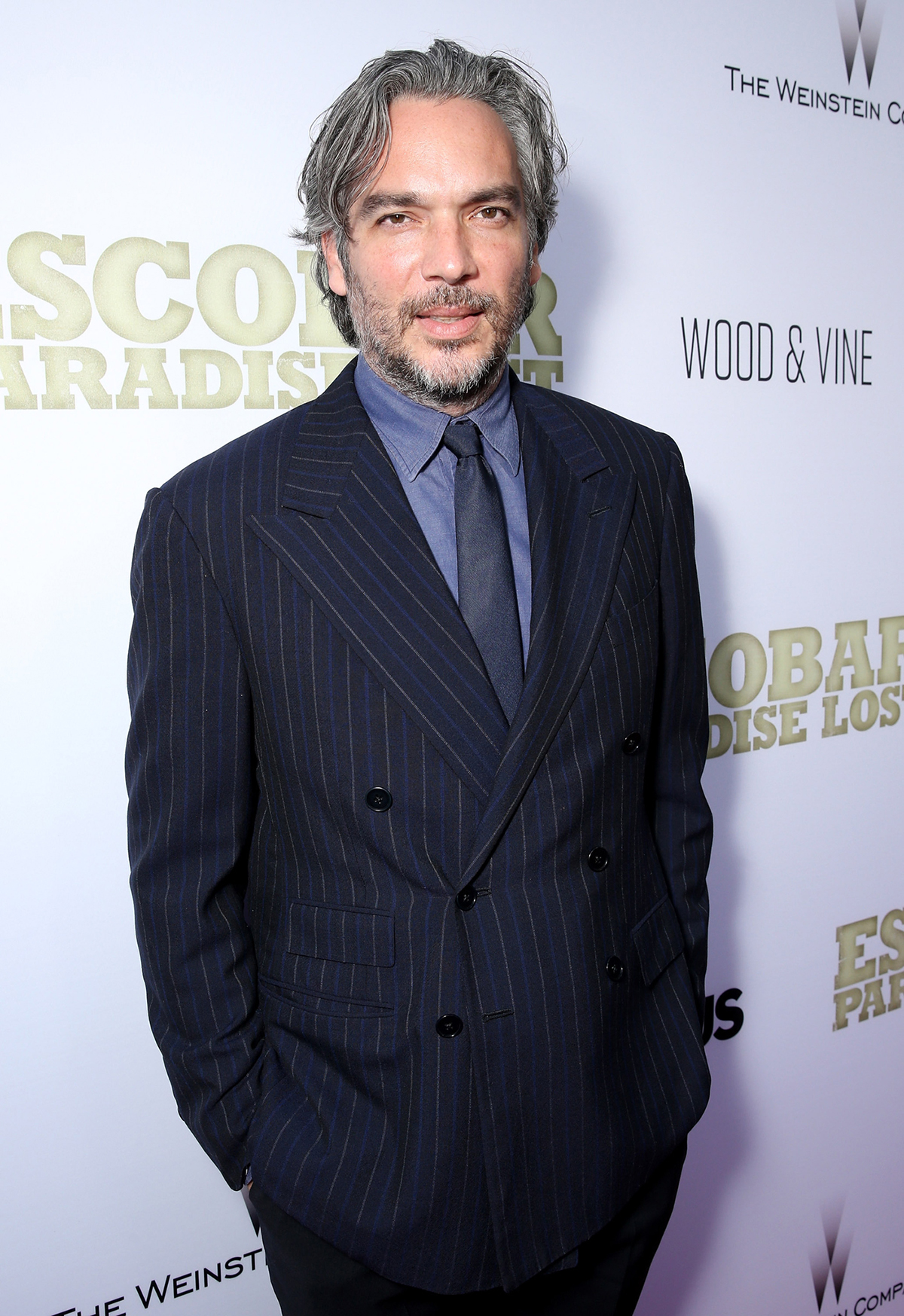

Andrea di Stefano. Photo courtesy: IMDB; (Below) Stills from The Informer

Journey to the End of the (American) Night: The filmmaker on The Informer, his explosive thriller that dazzles with its depiction of the dynamics and ganglia of the American organized crime as well as of the fight against it by the FBI and the police

The Informer by Andrea di Stefano (2019) is an explosive thriller, thick and compact as few others. It dazzles with its depiction of the dynamics and ganglia of the American organized crime as well as of the fight against it by the FBI and the police. The Italian-Roman director got his footing in the film industry first as an actor, both in theater and cinema: after graduating from the well-known New York’s Actors Studio, he worked with directors like Marco Bellocchio (in 1997, he played the protagonist of Il principe di Homburg, The Prince of Homburg), Dario Argento, Julian Schnabel, Ferzan Özpetek and many others. Having featured in several successful TV series since 1999, he started as a director in 2014 with Escobar: Paradise Lost — a story about the Mexican criminal played by Benicio del Toro. The Informer, Di Stefano’s second film, is an adaptation of Börge Hellström and Anders Roslund’s novel Tre sekunder, with a brilliant Joel Kinnamanin playing the title role. This interview was done (in Italian) during the fifteenth edition of the Zurich Film Festival and was first published in the November issue of La Rivista, the monthly review of the Italian Chamber of Commerce in Switzerland.

The Informer is your second movie after your long career as a film and TV actor. What did this “passage” mean to you and how do you look at acting now that you are “on the other side” of the camera?

It has always been a dream for me since I started acting to become a director on day. The director is the absolute narrator; it is a dynamic that has always fascinated me. During my acting school days, I used to go to the sets even when I wasn‘t working, to watch the director, to try to understand what he was doing... And, immediately, I felt a kind of instinct about what I would do, maybe differently, with respect to this or that scene. The transition was, therefore, very seamless. This was also because from the very beginning, I had started writing feature films. Before Escobar, I never tried to write any short film. It was as if I was able to “hook” [“picciare”, in Italian cinematic-jargon] the story; as if I had no doubts that I would certainly have managed it, almost in a delirium of omnipotence [smiles]. And I guess that those who believed in me, “felt” this form of… controlled madness.

Sounds like it was already inside you, kind of a form within the material in Michelangelo’s terms so to say…

I remember that when I was doing theater, in New York, one of my directors once told me: “You should be a director and not an actor”. I was terribly upset. Indeed, I was really mad. I was asked to stage a story in order to understand what I meant. So, at the age of 22, I found myself — as an actor — directing a scene, which turned out pretty nice. In short, it’s something I’ve always had: I felt potentially a director even before trying my hand at it...

Why has there been negative reaction of you turning a director?

I was very young and I wished to realize myself as an actor. I wanted be an actor. I loved to stay on stage. Evidently, that was the path that I needed to start before.

What fascinates you about directing?

That special calm during the process of writing when you feel that you somehow are cuddling all your characters, and you begin to know them: those moments, in short, during which you build the story are priceless. Of course, even as an actor, when you begin to put up a character and feel at ease, when you become someone else, then you perceive the beauty of a profession that allows you to give shape to stories. However, direction involves a great responsibility: high amount of financial resources, the need to set up the days, manage, join forces, somehow give a moral to the story... Plenty of things to consider.

Which directors or film schools influenced you mainly?

I admire many directors, but especially the entire Italian cinema formed me. Above all, I like the Italian screenwriting school’s ability to create characters, even if stereotyped, never predictable. You always manage to understand their motivations, through details, small things…For a long period of our film history, it was as if we were able to speak about intimacy like nobody else. I think of films like I Compagni [Comrades] by [Mario] Monicelli (1963), but many examples could be made of neo-realism... In those years, we had a unique screenwriting school.

Similar to what Martin Scorsese usually says.

We are unique since we have managed to ride the auteur cinema in such a creative way. In Roma città aperta [Rome Open City, by Roberto Rossellini, 1945], for example, the scene in which Aldo Fabrizi hits the head of the patient with a pan, is the result of a vital need, a response to the risk of being killed in turn, yet — an extraordinary fact — one laughs and cries at the same time. In short, there was a unique narrative magic in Italy. Perhaps precisely because, in those years, we had seen all that there was to see, we could describe certain dynamics better than others. And this tradition has always fascinated me.

Both your films deal with the issue of drugs. Why?

Actually, I didn’t care about drug much. In Escobar, we don’t talk about and cocaine never appears. Rather, I wanted to focus on the figure of this psychotic based on a true story capable of showing who he really was, at least this was my ambition. For me, even The Informer is not a film about drugs, but rather about violence, in particular about the violence in American system, as shown through the story of a man who ends up in prison, where he is somehow compelled to deal with gangs: you are forced to be part of it, otherwise they kill you; then an escalation of violent events develops, that leads him, after leaving prison, to face a kind of three-headed monster — the FBI, the police, and the crime — that is the Polish mafia (or more precisely the mafia from the Eastern countries). An inane, mythological struggle, so to speak.

Mythological in which sense?

Because he is a human being with an ordinary life, despite being in the prison, who is catapulted into extraordinary circumstances, both in terms of enemies and powers. And somehow he must be able to save himself. This man committed himself to saving his skin in front of these so-to-say “monsters,” somehow reminds me of certain mythological stories I read during my childhood.

… in a sense, forces (and people) with the power of life and death —with due distinctions obviously. Incidentally, I particularly liked the female figure of the FBI agent (played by Rosamund Pike) whom I found very beautiful.

These officers work very, very hard. In order to understand the context, dynamics and the story of Escobar, I had various conversations with some of them, who also were in contacts with informants linked with drug cartels. And I came across really impressive stories. It is anything but easy to play such a role, especially when one gets closer to and even fond of some human beings one wishes to help to change. Of course, they are criminals, yet each one with his own history, and willing to get rid of the underworld: people with families who suddenly might disappear, and nobody gets any news, not even their wives and kids. Perhaps their families do not have money to survive. Such dynamics interested me. Also, I liked the protagonist’s character: he reminds me of people with whom I collaborated for Escobar, men who are genuinely convinced to fight for good. Consequently, they take enormous risks (with anything but high salaries) in the name of ideal. People who go out and don’t know in the truest sense of the word whether they will come back home. An agent of NYPD [New York Police Department] especially helped me to write the character of Common [the American rapper and activist Common, formerly Common Sense, real name Corant Jaman Shuka Rashid Lynn]. There have been policemen at work every day on the street since 20 years. Everybody has his own story, the wounds, the bullets that had passed through… And if you ask them why they keep doing that, their answer is not about money, but other higher reasons… Certainly, there are exceptions, yet there are many of them who can hardly send their children to high school, to university; yet despite their extremely complicated existence, they continue to risk their life, and every night they put on the bulletproof vest and go out…

Would you say that this phenomenon is especially widespread in the US?

Well, it doesn’t look like we [in Europe] have the same level of criminality and, above all, we do not have the same number of loaded handguns in the streets. Owners of a gun — according to an American statistic — have 300% probabilities more to be gunned down.

What do you think of the recent debate (in Italy) concerning the emulation’ risk from young people of violent behaviors depicted in movies like La Paranza dei Bambini by Claudio Giovannesi (based on the homonymous book by Roberto Saviano, the Italian writer who became famous with his book Gomorra, 2006)?

The best answer is that of Scorsese. The work he does implements a narrative that is also educational with respect to the various generations. I think this also concerns Saviano or anyone who makes films from Saviano’s stories. One must represent that reality as raw and realistic as possible. That reality also belongs to the dynamics based on emulation; and somehow dominated by the feelings of urgency. I believe that anyone who goes out on the street with a gun to perform criminal acts does so starting from a need, and from a certain family history. Everything we see (and judge) as a civil society, moves from the outside, from a privileged position that allows us the luxury of pontificating about what should be done or not, to talk about the “massimi sistemi”, but this is a luxury for its own sake. For if there would be the intention to really change that kind of criminal behavior, one shouldn't look at the cinema or to narrators. Narrators do their job exactly as Saviano — and Scorsese — does.

More from Culture

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

THUMBS.jpg)