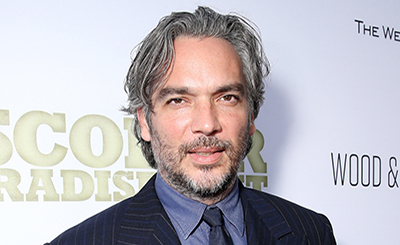

Hira Mani as Kashf in a still from the serial. Photos courtesy of Ham TV

The Hum TV drama — written by Imran Nazir, directed by Danish Nawaz, and produced by Momina Duraid — is a complete rarity. It foregrounds questions about religious exploitation vs the sacred, without moral simplicity.

“I have played many characters in these five years. I went on-set, donned the look of the character, played the part, and then signed another project and repeated the process for it … But Kashf … she stays with me. I am unable to let go of her. I don’t know when this will end, I don’t know what my own end is. All I know is that Kashf has me completely within her grasp. — Hira Mani, in an interview by Maisooma Batool, Oct 31, 2020

The Pakistani TV serial Kashf (Unveiling) on Hum TV — written by Imran Nazir, directed by Danish Nawaz, and produced by Momina Duraid — is a complete rarity. I am so lucky to have stumbled upon this show in St. Paul, Minnesota, at my husband’s insistence, where clever, glamorized, agenda-based TV shows with their bite-sized wisdom is standard fare. So, we watched it on YouTube, ads and all, and some of the early episodes with a friend who has promised to finish watching it in New York. Kashf foregrounds questions about religious exploitation vs the sacred without moral simplicity. The show startled me, and I tried to make my friends watch it: “It sounds dark,” they said. Writing this review/essay is my second effort at persuading my friends and readers to watch Kashf.

Kashf dares to engage with the sacred and the profane with the intensity of a Greek tragedy. It has deservedly won wide acclaim for its well-patterned story, plot, dialogue, brilliant direction, and extraordinary performances by the actors: Hira Mani, Waseem Abbas, Junaid Khan, Hajra Khan, Sameena Ahmed, Saleem Miraj, Saji Uddin, Lubna Aslam, and Amir Qureshi. Kashf, the lead character, played by Hira Mani reminds us of Alyosha in Dostoevosky’s Brothers Karamazov who lives and dies with a purity and gentleness that eludes everyone else. The collision in Kashf is between gentleness and careless cruelty, but the show throws this central question at the audience: “What if the original comes to us in the form of a counterfeit?”

At first, my teacher-mind kept making connections for the classroom: Is Kashf like Joan of Arc? Is Kashf like Antigone who gives up everything for her loyalty to a brother she does not even really like? Is Kashf in the predicament of Iphigenia in Aeschylus’s Orestia, the daughter who is sacrificed by her father, Agamemnon? Even the arrogant and insensitive Agamemnon had to make sure that Iphigenia is his child, and that he loves her like a father so that the sacrifice could feel like one. But Imtiaz, the father in this show — played brilliantly by the veteran actor Waseem Abbas — is a father in name alone, a father who does not love his children because they are daughters who are burdens until they can be turned into investments.

In an interview titled “Who says that Kashf does not have a happy ending?” Danish Nawaz, the director of Kashf, claims that he “does not think that Kashf is a tragedy” even though the events are tragic. Whether Kashf is “a tragedy or not” could be debated, but the show has the narrative structure of a Greek tragedy. The lead character — young Kashf — is trapped in an impossibly difficult situation, and there are no easy answers to what can be done, and that is what interests us as viewers. Simon Critchley, in his book The Tragedy, the Greeks, and Us, argues that this question of “What should I do?” animates ancient Greek tragedy. Critchley says that the gift of tragedy to the spectator is to make us see “a disoriented, baffled character struggling with this question of “What is the right action?” This is why the ancient Greeks watched tragedies by Sophocles, Aeschylus, and Euripides so that they could come face-to-face with the effects of mysterious unknown forces that besiege human beings. Kashf shows the mysterious forces that surround us by using clairvoyance, telepathy, dreams, and prayer. These may not fit with our current ideas about skepticism and science, but they take us into unknown parts of ourselves.

The plot of Kashf is simple: there are two brothers, Imtiaz and Faiyyaz, and they live in adjacent houses and share a terrace. Faiyyaz’s family lives upstairs, and despite his wife’s contempt for her husband’s brother’s family downstairs, this is a family that Tolstoy would call a “happy family.” They love their children Wajdan and Shumaila more-than-adequately and equally. Imtiaz’s family is poor, chaotic and “unhappy” because the father-figure, Imtiaz, is fraudulent, selfish, and greedy. Imtiaz wants his daughter’s clairvoyant dreams to make him rich. He is also servile, and servant to the diabolical Matiullah — the arch-villain — to whom he owes money. Imtiaz’s mother takes her son’s contentious point of view in everything, is demanding, bossy, and loves eating! Imtiaz’s sister, Ashi, who had been married off to the violent and diabolical Matiullah by her brother Imtiaz, now divorced, lives with Imtiaz and his family because her income as a teacher is useful to the struggling family.

Kashf, the oldest of Imtiaz’s three daughters, is distinct. Kashf is also the only one in the family who prays with any moral attention, while the others sanctimoniously invoke Allah every chance they get. Kashf is betrothed to Wajdan, her cousin, and they naturally belong together. Kashf discovers that dreams happen to her in which she can foresee shadows of future events, but unlike a clairvoyant, she has no control over them; nor is she a Pirni. The process of setting her up as a Pirni begins when Aunt Suraiya comes home to thank Kashf for the dream that miraculously saves her life and keeps her from getting on a plane, which she learns has crashed. When the aunt presses 5,000 Rupees in Kashf’s hand, saying that Kashf henceforth is her murshid, we see Kashf flinching in terror from what she and we the viewers recognize: that her dreams can no longer be anything but clairvoyantly true, and not even her own anymore. Kashf’s father immediately sees a business opportunity here. A clairvoyant Pirni in today’s meretrious, guilt-heavy market is currency itself.

But Kashf is a real artist; a real artist involved in making counterfeit paintings. Unlike Joan of Arc, Kashf does not claim that her revelations are proof of Allah’s benediction. On the contrary, she is baffled and asks Qari Sahib, a true Pir, what her dreams mean, and how an ordinary girl like her, who cannot even pray without getting distracted, be the recipient of this gift? Qari Sahib tells her that she must keep her dreams to herself. Kashf, however, finds her dreams so terrifying that she cannot keep this secret to herself. Qari Sahib also tells her that her simplicity, humility and gentleness is the reason why Kashf is “the chosen one.”

“Chosen” is the last thing Kashf feels. She is speaking a strange new language over which she has no control. Her prayers get more earnest. He sets up a “Kashf Bibi Ka Asthana”, and Kashf is handed a terrible new responsibility, to dream dreams that foretell people’s futures, and sit on a pulpit as a Pirni. Hira Mani’s face animates gentleness. This really is the life-affirming power of this show. Religion for the marketplace — this is her father’s plan. The business takes off; people start to pour in for solace, and the money starts to pour in. Imtiaz is the gatekeeper counting the coins, making sure no woman gets in to see Kashf unless a “Nazrana” has been deposited in the donation box, while Kashf’s family-members harangue her for money.

Kashf sees everyone around her changing, and she sees the bad faith. She goes silent. Her family gets richer every day. The darkness begins. Her loneliness gets deeper. And we ask ourselves: Why does she consent to her father’s demands? Does she not recognize who he is? Perhaps, that is a central quality of goodness, that it wishes good for others — even for people like Imtiaz who is after all her father, even if only in name.

Only Wajdan’s love and his unquestioning loyalty is vouchsafed for Kashf. Only to Wajdan, she remains real. The love and faithfulness of Wajdan and Kashf where they give each other everything, even what they do not possess, is beautifully evoked, and makes this show a poetic tragic love-story like Sadqay Tumhare or Devdas. What Wajdan gives, or gives up, and how he abandons himself in his love of Kashf startles the viewer!

But Kashf is beyond the narcissism of passion; she is elsewhere.

If Imtiaz, her father, strikes the first blow against Kashf, Zoya, her youngest sister, strikes the second blow. Zoya covets Kashf’s fiancé, Wajdan, with a greed that matches Imtiaz’s greed for money. When Kashf speaks her heart to Wajdan, telling him how devastated she is, and how strange all this is, he begs her again to go away with him. Zoya records this conversation and publishes it on social media, revealing to everyone that Kashf is not a true Pirni but a hoax who treasures a secret love. The ironies of this are not lost on the audience! Is Kashf the shadow or the reality of the pure and gentle Pirni? Is Kashf saintly? Is Kashf the original figure of the sacred who is forced into the profane embrace of religion by fake clerics like Mattiuulah and her business-agent father? We wonder about this when Kashf is looking at herself in the mirror in her new garb of a Pirni. Kashf pleads with her mother to stop this Asthana: “We are building our house with the suffering and misfortune of others.” Her mother persuades her that she is doing God’s will.

Page

Donate Now

More from Culture

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

Loved reading the review. Thoughtful and complex like the characters themselves. Can’t wait to see more of such reviews and “kashf!”

Dipankar Mukherjee

Oct 16, 2021 at 07:05