Photo courtesy: starinthestone.wordpress.com

On the anniversary of demonetisation, a story enmeshed in economics, neoliberalism, global geopolitics and more

I

Scene One

‘I am my own Ghost’

Four butoh dancers – in white body make-up — appeared on the dark stage. The movements were slow and unclassifiable; the background music was strange and grim. But the sound had a hypnotic and haunting quality — like the soundtracks that play during the scenes of radio-active ruins or dusty wastelands, in films of dystopia and science fiction.

Professor Shankarnath Sanyal had already read the leaflet that waited for the audience on every seat. He had never been late for a play in his life. This time around, he had arrived even earlier; he had feared that it would take a long time to find a parking near Gyan Manch — the old auditorium in Pretoria Street. But he was surprised to find a spot easily in one of the nearby lanes. It was a busy area near the upmarket Camac Street — a potent blend of commercial, official and residential spaces.

The parking guy, while slipping a parking ticket under the right-wiper, had remarked that ‘things are still slow; the parking-fee collection is down by thirty-five percent’.

After parking his small car in between two large SUVs, the professor walked to the auditorium, bought his hundred-rupee ticket from the counter, sat down on a chair in the lobby, put his mobile phone on the silent mode and passed time by observing the surroundings.

The small takeaway — a ‘snacks bar’ — at the side of the lobby wasn’t prepared to serve tea or coffee. The man, behind the marble counter, had signalled to him that he will take ten more minutes to get things going.

The professor was recognised by a young woman — a student of Masters of Arts — Comparative Literature — from Jadavpur University who was part of the production team. Aaloka came up to him for a chat. She also handed him the white leaflet that spoke about the play in greater detail than the brief material that was dispersed widely via the social media.

‘Please don’t scold us sir; the leaflet has few mistakes. Tisha was supposed to check the matter thoroughly. But she had an emotional episode with her boyfriend and lost her concentration.’

‘How is Tisha now’, enquired the professor, ‘Is she here?’

Aaloka replied ‘she is supposed to come’; but she is still ‘sulking ever since the break-up’. She has also missed a couple of their work meetings.

‘But don’t worry sir,’ Aaloka assured, ‘I know Tisha is one of your favourite students. She will be fine soon.’

Aaloka knew that Tisha’s romance had begun under high-stress situation when Tisha met the guy — ten years elder to her — in a bank queue after 8/11.

In less than a year, Tisha has already ‘broken-up’ thrice and ‘patched-up’ twice with her boyfriend.

Aaloka felt that the direct link with 8/11 is influencing the nature of Tisha’s stormy relationship. She had this notion that the circumstances or the time when relationships begin, tend to leave a lasting effect — either positive or negative — at an unconscious level. Or in other words, Aaloka believed, the time of all beginnings follow people in some odd inexplicable way.

Aaloka was well aware of Tisha’s inclinations and psyche. Tisha had confided to Aaloka that her boyfriend is not the right kind of person for her; he lies continuously, suffers from intellectual hollowness, lacks heart, emotionally drains her and saps away her energy. There were other issues as well. Yet Tisha had already returned to him twice.

Aaloka had told Tisha that ‘you don’t have the naïve hope that things will somehow improve with time or you will manage to rescue or transform him. It is not your heart but something else that is luring you; something visceral, like the workings of the primitive reptilian part of your brain. You are responding to a spirit that calls you to venture into the darkest night. You are doing this willingly and knowingly. You are well aware that lightness, peace, love and happiness don’t await you there.’

Aaloka knew that Tisha was being corroded by her internal conflict — dump the wrong person forever or succumb once again to her weakness.

Aaloka feared that Tisha will be back with her boyfriend once again when the grievances prick less and the tempers cool down. It was a dark attraction based upon the ‘reptilian brain’ — the human soul had nothing to do with this. Sense and intelligence are not expected, when the base emotions dominate.

Aaloka felt that this is also one of the prime reasons — apart from habitual attachment and unfavourable circumstances — which force women submit to abusive relationships, swallow injustice and endure oppression with silence.

Aaloka had already published her ‘reptilian theory’ in an online literary journal where she had argued: ‘it was due to the “reptilian brain” that humans struggle to become humane. Fear is the central emotion of the reptilian brain. Power and money help to convert fear to “organised fear”, just like organised crime is structured by an elite cabal. The selfish egoistic “reptilians” who use “organised fear” to manipulate people to their advantage are the “devils” of our modern world and the prime enemies of humanity.’

Aaloka had also written: ‘the horns of the modern devils are invisible; they come wearing nice clothes and alluring perfume. They thrall people with their charming speech. They often see themselves as mythic “crusading” characters of a morality play that is fake and insincere.’

‘To see through the carefully manufactured image of the modern devils is a skill, we need to master.’

‘To break a devil, one has to break the idea that the devil has constructed in the minds of the people. That’s why right information and accurate analysis are the enemies of the devils. This is also the reason why the people who can see and speak are seen as enemies; all efforts are made to buy, gag or silence them.’

‘The aura of power overwhelms the mind. Most people get hypnotised by power, like young children watching a magic show.’

‘One has to see through the façade of power. The neuro-toxicity of their narcissistic ambitions can be easily seen if one has inner stillness and mental discipline. The constant lies, the tiresome doublespeak, the mocking arrogance, the perennial instinct to blame others, the obvious hypocrisies, the selective righteousness and the utter lack of empathy expose the dark inner abyss of their cold reptilian being.’

*

After Aaloka left, the professor went for some tea that was now ready. The hot tea in the professor’s cup was filled up to the brim. He spilled some of it on his right index finger while manoeuvring the cup through the people who had gathered at the ‘snacks bar’ counter.

Once the professor found a clearing, he transferred the cup to his left hand and was sucking his right index finger, when he was accosted by a couple of acquaintances from his academic world.

The professor feared the small talk that one has to do with the acquaintances at social and cultural events. One doesn’t have the confidence to reveal oneself fully in front of people who are neither friends nor colleagues. The tedious ritual bored him. But he had no way to avoid it in this occasion.

The acquaintances discussed national politics with him, while he sipped tea from the moist paper cup.

The tea was really awful, and the conversation, thoroughly unenlightening.

*

When the door to the auditorium opened — fifteen minutes before 7 pm — the professor took the opportunity to excuse himself from his company. He dumped the paper cup into a garbage bin and was the first one to queue up at the door.

Inside the auditorium, the air-conditioning system was turned on in advance; the professor felt cold; a shiver ran through his body.

It was the second week of November; a ‘warmish chill’ had already arrived in Kolkata. The professor liked to use the oxymoronic phrase to describe the current weather: it was the time of the year when one has use a sheet to cover oneself up during the night, and yet stick one leg, outside the covering!

This was also the time when his usual arguments with his wife — about the fan speed — spiked and intensified.

The professor hoped that once the audience arrives in the auditorium, the cold will be tempered by their presence.

The professor surveyed the empty seats and chose instinctively. The seat was in the middle of the rows and faced the centre of the stage — now enveloped by thick satin curtains.

A detailed introduction to butoh was given on the leaflet that was kept on every seat. The professor now had two copies of the leaflet. He sat down, made himself comfortable and read from the leaflet that Aaloka had handed over to him.

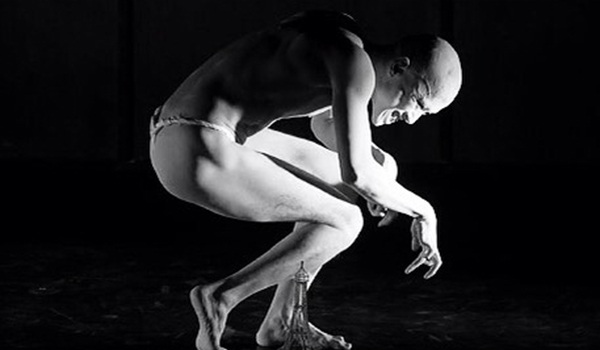

‘Butoh — a form of Japanese dance theatre — appeared in the post-World War II Japan under the collaboration of Hijikata Tatsumi and Ohno Kazuo. It was a response against the Japanese dance scene that Tatsumi felt was “imitating the West” and wished to “turn away from the Western styles of dance, ballet and modern” and embraced the “squat, earthbound physique…and the natural movements of common folk”.

The movement found a form as “ankoku buyou” that meant “dance of darkness”. The first butoh piece Kinjiki (Forbidden Colours; based on a novel by Yukio Mishima) by Hijikata Tatsumi premiered at a dance festival in 1959.

In the 1960s, Hijikata changed the word “buyou” to “butoh” — a long discarded archaic word that meant dance.

Hijikata was inspired by writers such as Mishima, Artaud, Genet and de Sade. He delved into grotesque, crude and decay, while exploring transmutation of the human body into other forms, such as those of plants and animals.

While Hijikata is acknowledged as the “architect of butoh”, Ohno is regarded as “the soul of butoh”.

Butoh has undergone further transformations; the collaboration of Hijikata with Ashikawa Yoko in the 1970s was revolutionary when the exterior body was reintegrated with the interior universe; the invisible subjective was brought to the surface.

In the 21st century, butoh is becoming more popular. The dancers from all around the globe are freely interpreting and performing butoh with their own aesthetical ideals.

However, butoh is characterised by performers in white body makeup with slow hyper-controlled movements which mirror the inner nervous system or the mental state that is marked by distress, pain, bewilderment, alienation, numbness, anxiety, shock and entrapment.’

*

The leaflet also said that this was the first time that a butoh performance — by a city-based dance group — is taking place in Kolkata. The play — Demonetisation Tales: The Ghost Detective — imbibes butoh to present ‘an imaginative work that combines dance theatre with traditional theatre’.

The plot of the play was also given in the leaflet. Four butoh dancers represented the souls of the dead who had died due to demonetisation — described as ‘8/11 D-Day: D for Doomsday’. Since their time wasn’t up as per ‘the natural order’, they have been ‘condemned to roam as ghosts’, till the ‘universe processes their ethereal karmic souls into other material forms of life’.

One of the dead was a detective of an agency called ‘Cat Eye Private Limited’ who had suffered a heart attack because he didn’t have enough ‘valid cash’ with him, when his mother’s health deteriorated and the doctor had suggested urgent hospitalisation.

He could have managed the situation with a calm head. But due to a medical history of severe hypertension and chronic anxiety attacks, the detective had succumbed to the pressure.

The tragedy occurred in reverse: he died, while his mother survived.

The detective is represented by the sole male performer of the group of four butoh dancers. He now wishes to solve the mystery why demonetisation was actually done.

Absolved of his material body, and reduced to the invisible ethereal body, the only way the ghost detective can ‘solve the mystery’ is to roam within those he is emotively connected with — his friends, family, colleagues and clients — and hear what the people are discussing in their private lives.

From their conversations, the ghost detective hopes to figure out the ‘real reasons’ behind the ‘stated reasons’, and clear his bewilderment.

The ghost detective is accompanied by three female butoh dancers — the souls of dead — who also wish to understand the mystery behind 8/11 that has caused death, destroyed livelihoods, triggered job losses, shrunk consumption, crashed private investments, shut down small businesses, sent migrant labourers back to their villages, broke the psyche of the people, disrupted all aspects of life and took the economy to a self-inflicted contraction.

‘Why did I have to die?’ — is the question that pursues the ghost detective as he relies on the living to offer the answer that he seeks, and thereby, bring to himself: rest, comfort and peace.

*

The introduction to butoh and the plot of the play was read out at the start in four languages — English, Bengali, Urdu and Hindi. All the four languages were to be used in the play, even though — as the presenter declared — English will be the dominant language.

The professor felt that it was a smart move to give away the plot in the beginning: some of the audience might not have read the leaflet. The director didn’t want the audience to suffer from ‘what is going on’, and wished to focus on ‘what happens next’.

*

After the four butoh dancers arrived on the stage along with the haunting music, the atmosphere became other worldly. The ghostly bodies with white makeup moved slowly and unexpectedly. The ghost detective’s motions were weirder — suddenly the shoulders shifted to the right, the body contorted, as if it was suffering from an inner spasm; the legs wobbled, the balance was lost, and then regained.

The female butoh characters remained behind the ghost detective — all three of them seemed to have a character of their own which was displayed by their body language and motions. None of the butoh characters were moving remotely like any other. But all of them looked like souls in severe existential distress.

After a longish sequence of dance, the ghost detective spoke in a voice that seemed to come from a great distance. He was speaking from his throat — like the throat chanters and singers — such as the Tibetan Gyuto monks. He was having difficulty in speaking. Words were interspersed with gaps, groans and silences. He finally delivered his first two lines — in tone that seemed to be cracking due to severe weight — ‘I am my own ghost. I want to know why I died.’

II

Scene Two and Three

‘The People Speak’

Scene Two was a farce. There is a house party going on where a torrid discussion about the pros and cons of Demonetisation break out between the guests. The audience is told that it is happening in January 2017. Someone recalls the anxieties of the first two months: the rush to find valid currency to take care of the cash requirements for immediate survival, the imposition of restriction to withdraw one’s own money from the banks, the long queues, tempers flaring because of new notes running out every day before everyone could exchange old currency or withdraw money in new currency, tedious battles on social media and souring of personal relationships.

They also discussed how the jewellery shops in the posh malls were kept open throughout the night after Demonetisation was announced on television and how they were getting calls to convert any amount of old currency from people affiliated to a single political party who had an unlimited cache of new currency, when the banks didn’t.

Going by the clothes, the pleasantries and the mannerisms, one could understand that the affluent guests of the house party came from the upper middle class, and even higher.

But soon the pretentious masks come off. Two male guests — from the opposite camps of the debate — start resorting to vile abuses and physical fights. The inherent contradictions and the toxic masculinity are exposed. They violently go at each other, while a couple of others try to restrain them. Someone throws cake at them; bottles break; cushions fly; a woman faints; and a free-for-all farcical chaos ensues.

This is witnessed from the periphery by the butoh characters whose nervous movements also synchronised with the tension of the situation. They seemed to be confounded by what was going on; one of them had fallen on the floor while holding her head in unbearable agony.

*

Scene three shifts outdoors to a neighbourhood street tea shop. It has a rock bench where people come and sit, while they discuss various burning issues of the day.

A series of characters come and go and give their opinions to the bald tea-seller, and Comrade Hazra who is sitting on the bench and thinking aloud about what the people are saying.

The stage has a small temple by the side of the street tea shop where the people — who are uninterested about the happenings around the tea shop — are also coming, taking part in rituals and going away. They had no further role in the drama.

The audience gets to know that it is October 2017, and the sales of ice-cream during the Durga Puja have been the lowest ever in the history of Kolkata.

Working class people are represented in this scene, where they speak about the sufferings they are compelled to face due to the Demonetisation policy and its after-effects.

Few middle class professionals also arrive and they chat with Comrade Hazra — a feisty feminist: a well-known person in the neighbourhood who had lost badly in the previous Assembly elections to a Trinamool Congress rival.

Comrade Hazra, however, blamed the ‘a certain misogynist dinosaur of Alimuddin Street’ — the headquarters of The Communist Party of India (Marxist) — for giving her ‘a rural constituency where she had no chance of victory’.

The professor knew that since the government hasn’t been transparent about the Demonetisation Policy, many theories have taken birth. All the common theories which were floating around and what people are talking about — in the real and the virtual world — were brought in within the play: the government was influenced by Washington aka the Obama administration and the globalist banking cartel led Bilderberg Group of super elites, the government wanted to favour certain Indian crony corporations and financial applications offered by them, the government wanted to ‘engineer’ the unorganised sector in the favour of corporate interests, the government wanted to execute ‘organised looting’ and ‘legalised plunder’ — as alleged by former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh who also called the implementation of the policy ‘monumental management failure’, the government thought that they will make a lot of profit because they speculated that a huge amount of black money won’t be deposited back in the banks and the government will find a lot of money in the books — freed of all liability — that could be used to write off the humongous Non-Performing-Assets or bad debts of certain favoured corporations, the government wanted to destroy the cash black money of the opposition parties and paralyse them, the government wanted to re-capitalise the banks with people’s money, the government also took the decision in view of Uttar Pradesh elections and the government wanted to do a ‘morality play’ to find a higher ground for Prime Minister Modi — as a messiah — in the eyes of the people, but misled the people by saying it was done for the sake of the poor — in a series of flip-flops about the real objectives.

Comrade Hazra — whose party has a tradition of opposing the global geopolitical wars for profit and imperialism — was focussed on the Washington Beltway angle.

She was giving a speech to the bald tea seller who didn’t understand anything what she was saying. But he was nodding away in agreement in order not to offend Comrade Hazra.

Comrade Hazra had taken out her phone and was reading from the revealing article — that has gone viral — by the independent German financial journalist and economist Norbert Haering titled ‘A Well-Kept Open Secret: Washington is Behind India’s Brutal Experiment of Abolishing Most Cash’.

‘Listen to this Bholuram’, Comrade Hazra was saying to the bald tea seller in English — a language Bholuram didn’t understand, and reading out excerpts from the article.

The bald tea seller only had one dialogue that he delivered intermittently after Comrade Hazra finished some of her many points.

Bholuram did the typical ‘Indian nod’ — shook his head sideways, to the left and right — to display his agreement, and occasionally remarked, ‘Sahi hai. Sab paisa khata hai. Sab jhoot boltey hai. Sab papi log hai. Bure karmo ka phal toh milega. Sab narak mein jayega. Kisko ghoos dega; kisko darayega; kuch nahin chalega. Sab bade bade laal-batti-wale admi narak mein jayega. Sahi hai.’

*

Comrade Hazra was also quoting from another article by F. William Engdahl — a strategic risk consultant, lecturer and author — who wrote an article that was first published in an online journal New Eastern Outlook.

Comrade Hazra said, ‘the article by Norbert Haering and the one by Engdahl titled The Sinister Agenda Behind the Washington War On Cash has been published worldwide, except in the Indian media, that harbours a soft corner for the Anglophone West, and prefers to bury its head in the sands when it comes to America.’

‘Truth to power, my foot,’ uttered Comrade Hazra with sarcasm and venom, ‘the colonised minds, the bootlickers, the cowards, the opportunists and the hypocrites.’

The above statement struck a chord with a section of the audience. They clapped — someone also whistled — to display their approval of Comrade Hazra’s observation of our society.

Comrade Hazra went on to praise the independent journalists, commentators and researchers who are ‘fearlessly uncovering the veils which cover our minds’ for ‘the sake of truth, justice, progress and humanity’.

Nowadays, one doesn’t have to depend upon the local and the national media to get to hear about other perspectives and to broaden one’s horizon. One can easily follow various alternative media sites and independent journalists through social media to figure out the real truths amidst the agenda-laden biased narratives of the government and the corporate media.

This is the prime reason why the ‘grip’ of the ‘mainstream media’ upon the people’s consciousness is losing effect. More and more people — who are tired of being victims of outright lies, spin journalism, manipulations and ‘psyops’ — are seeking out alternative sources of news, information and analysis.

Even the professor had read the article by Engdahl, when it was shared on social media by a friend of his, who had also forwarded it to a bunch of people via WhatsApp. Going by the reaction of the audience, the professor could gather that more people were aware of the articles, than those who were hearing about them for the first time.

Professor also knew that Prime Minister Modi had started giving out feelers about ‘cashless society’ as early as March 2016, when he spoke about the topic in ‘Mann Ki Baat’ — his address to the nation via radio. He linked ‘cashless society’ to anti-black money/ anti-corruption crusade — an idea that had no actual logical validity: both Germany and Japan are ‘developed economies’ and ‘low-corruption nations’ — both of them overwhelmingly prefers to transact in cash.

So does India; the people have returned to cash transactions, after a brief spike of ‘digital transaction’ that was brought about by the scarcity of the new currency notes, just after 8/11.

The professor always suspected that the government’s anti-black money drive wasn’t sincere; it is more of political propaganda to give itself a higher moral ground. One knows that the government has made anonymous political funding easier for the corporations, made the right to information act more opaque and hasn’t taken any action on the elite individuals who have been named in the Panama and the Paradise papers.

The black money of the elites weren’t black enough; when 60% of the national wealth is held by 1% in India.

The government is trying to extract ‘cash black money’ — estimated to be about 6% of the wealth holdings — from 99% of the population who hold 40% of the national wealth!

Even Samuel Beckett — thought the professor — wouldn’t have found a better plot for his theatre of the absurd.

*

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

WOW!

Robin Sen Gupta

Nov 8, 2017 at 10:34