Vaddey Ratner. Photos courtesy of the author

Vaddey Ratner, author of Music of the Ghosts, on her attempts to imagine the depth of suffering that her father might have endured after he was taken away by the Khmer Rouge regime and her reflections on what his journey might have been like

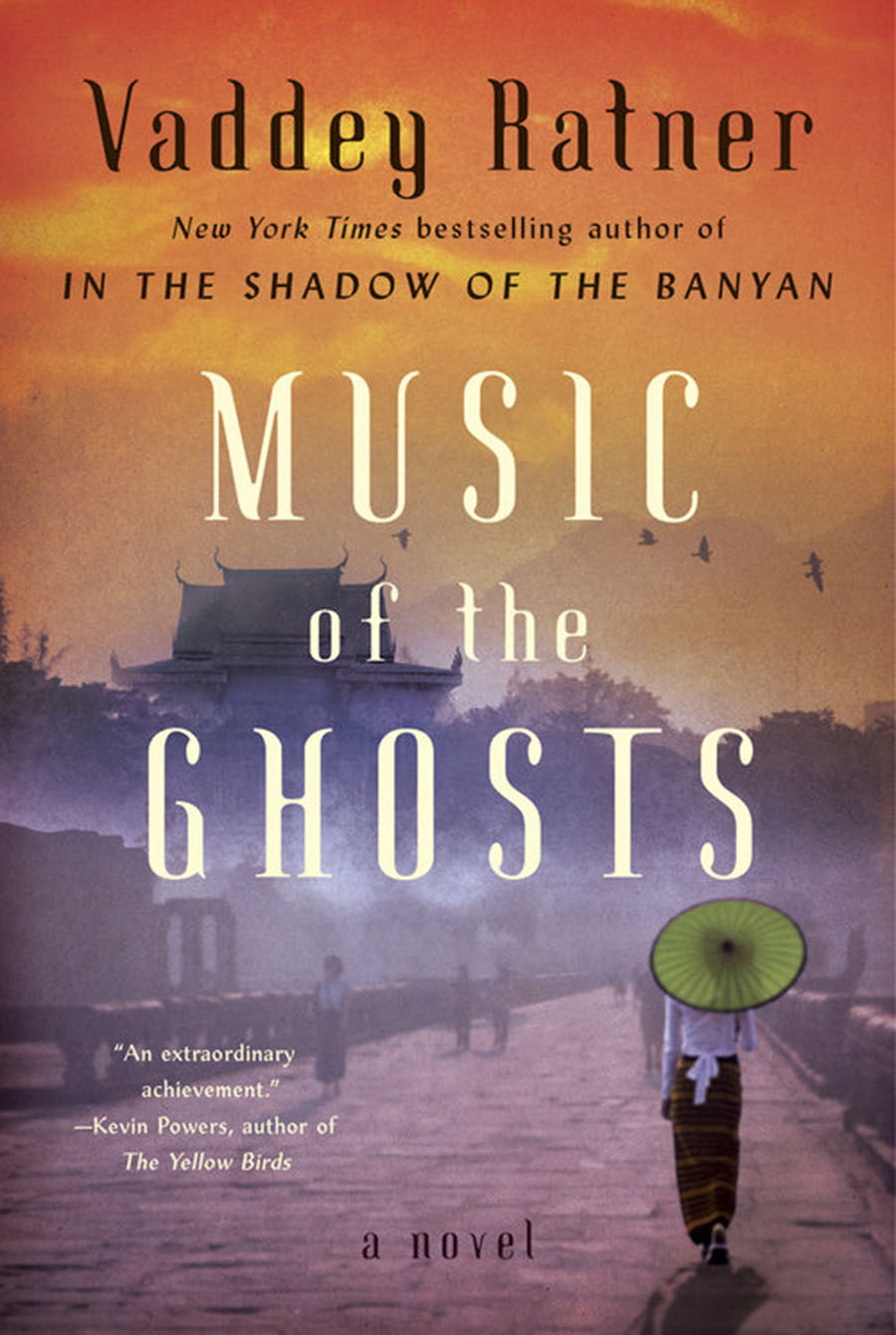

There’s certainly something redemptive in the ability music has to transport you emotionally, that ability to visit another place, another time, and return,” says Vaddey Ratner, the author of Music of the Ghosts, in the second part of an interview with The Punch. The novel, published by Simon & Schuster in April this year, has been described as a “tragic odyssey of love, loss, and forgiveness in the wake of unspeakable horrors . . . a moving tale of hope and heartbreak ...,” by The Publishers Weekly.

Ratner’s previous novel, In the Shadow of the Banyan, was a New York Times bestseller. Her second novel is about a 37-year-old American woman named Teera who returns to her homeland after receiving a letter from a mysterious man who claims to have known her father before he disappeared in the holocaust at the hands of Khmer Rouge. She returns to her homeland for the first time after her harrowing escape as a child refugee more than two decades earlier and carries back with her the ashes of her recently deceased aunt and a letter from a stranger who claims he knew her father in Slak Daek, the notorious Pol Pot security prison where her father disappeared.

When she arrives, Teera finds a country of survivors, where perpetrators and victims of recent atrocities are finding a way to live side by side. She reacquaints herself with places that ignite long-buried memories, meets a young doctor who begins to open her heart to a new Cambodia, and prepares herself to learn her father’s fate from the author of the letter, known as the Old Musician. Now a half-blind elderly man who earns his keep by playing music at a temple, the Old Musician waits for Teera’s visit, anticipating the confession he must make. Together Teera and the Old Musician confront the truth of their intertwined past, weaving a redemptive melody that will leave both transformed, and freeing Teera to find a new home and a new love in the places she least expects. Talking about Teera’s quest to find a home, Ratner says, “Home is not an immovable place. The journey is the home.” Excerpts from an interview:

The Punch: Tell us about the process of writing Music of the Ghosts. At the heart of the novel is the mystery surrounding the disappearance of Suteera’s father. This again has a personal parallel as your own father disappeared soon after the Khmer Rouge came to power. Tell us about your struggle to come to terms with his disappearance and living with the mystery about his fate. And also, how you processed this personal pain to write about Suteera’s journey to find the truth about her father’s end.

Vaddey Ratner: In a sense, my experience of the Khmer Rouge is divided in two. First is the direct experience of survival, which I detailed in my first novel, In the Shadow of the Banyan. I endured brutality and extreme deprivation, and I survived. The child that went through that is still alive to me as she was in that time. I was able to move on, to live my life. Yet, in moments of quiet I can still access that fear so readily.

Second is my struggle with the deep, unanswerable questions that form in the wake of survival. How do we move on from such loss, from such complete devastation? What if we never find out what happened to those we loved? What is the purpose of our survival? Writing Music of the Ghosts is my attempt to answer these questions.

The scariest aspect of the writing was trying to imagine the depth of suffering that my father might have endured, particularly after he was taken away from us. When I was a child, I felt only my own pain. I could imagine nothing more terrible than losing my father. As a grownup, and a parent, I began to reflect more on what his journey might have been like. If I can put myself in his place, to imagine the suffering that my father might have endured, and if I can emerge from the process of imagining that, and do something good with it, then I can still move forward. But the struggle is never finished. The questions endure.

The Punch: Music of the Ghosts is also an enchanting exploration into atonement and forgiveness. Were you interested in bringing the perpetrators and survivors together and chronicling their collective efforts to mend a country trying to cope with the scars of its violent past?

Vaddey Ratner: The reality of Cambodia is that survivors — victims and perpetrators — live side by side. In the novel, I aim to provide an example of how the confrontation between the two can take place, within the personal sphere of wrongs that are so intimate. It was also very important for me to show this in the language we use to speak to one another as Cambodians.

For example, in our culture, we don’t often say “sorry” because the very word to express this means to ask for punishment. It implies acceptance of and accountability for the wrong you’ve done. This turns the table for the other to either give or to remove the punishment, to say whether the suffering will end.

A lot of international attention has focused on the legal process as a route to justice, but for many ordinary Cambodians that feels like such a distant goal. Yet, we do have traditions outside of the courts, places in which those who’ve done wrong and those who’ve been wronged can come together. One of these is the Buddhist temple, where a particular language of atonement and forgiveness is used.

The Punch: Has writing this novel brought you closer to a sense of closure? Can there be closure in the face of such suffering and sacrifice?

Vaddey Ratner: When you are wounded, you don’t just wrap up the wound and forget about it. You continue to examine it, to dress and tend to it. Years later, when all that remains is a scar, still you return to it, and whenever there is a throb of pain, you are reminded. The wound is always there. The only healthy way forward is to accept that it will always be a part of you. It can neither be erased nor denied. It is not the whole of you, but it is an element that makes up who you are today.

The Punch: The novel is divided into three “Movements”. Did you have to work on its structure — the three movements coupled with interplay of past and present? Were you interested in exploring the redemptive power of the music and the various ways it can help heal?

Vaddey Ratner: I’m glad you asked this, because I find that, with each novel, I face the sobering reality of learning to write all over again. With Music of the Ghosts, there were many challenges, but the structure came intuitively. I heard it first. It came to me as a musical composition. I knew there would be a Prelude, three Movements, and at the end even an implied Coda: a note of healing, moving on, summation.

The interplay of past and present comes from the sense of time that I’ve always felt as a Cambodian, and that was reinforced while living in the country again. In our language, verbs have no past, present, or future. Rather than being lined one behind the other, there’s a sense these exist in parallel. It’s not that one experience is over and the other is present. We continue to live them both. The past continues as an emotional experience.

So it made sense to me to write this way. I had to create a sense of parallels, gliding connections across time, while keeping my readers in step. You’ll notice there are passages from the past that are told in the present tense. We don’t have a verb tense in English for an experience that occurred in the past but that feels so present you continue to live it.

To this day, it sounds so strange to me to say, “I loved my father.” He may be gone, but I love him still. I remember when I came to a point in my understanding of the English language that I had to learn to make this distinction, so as not to confuse people. I had to learn to express my separation from the past: “My father was…” That was a sad day in my learning.

In Khmer, when I speak of my father, the language allows him to be alive. It would be rude to ask, “Is your father still living?” So people, ask, “Where is your father?” And the answer, translated literally, means “he has a divided self.” It means he is not fully here.

Music, likewise, sets no boundaries on past and present. Its language, its power, comes from invoking emotion. If a piece of music speaks of night, that’s what you feel, no matter the time of day you may be listening. I tried to convey this musical quality in the structure of my own writing. There’s certainly something redemptive in the ability music has to transport you emotionally, that ability to visit another place, another time, and return.

There’s a line in the novel, when the Old Musician imagines his daughter waking to a tune she is humming: “This is how one should always re-enter the world from whatever sojourn, he thinks. With music.”

The Punch: Tell us something about the Old Musician. If Suteera is your alter ego, he is your father’s doppelganger. Tell us how you crafted his character. Have you known artists like him who had believed the Khmer Rouge’s illusory promise of a democratic society and were similarly betrayed?

Vaddey Ratner: Like my father, the Old Musician in his youth did pin hope on the possibility that the Khmer Rouge might be able to address some of the grave injustices and inequalities of the old society. And, like my father, he was betrayed by the revolution. His willingness to sacrifice himself in order to save his family, and his deep connection to his daughter, also parallel my own father’s experience.

Yet, it’s not simply that the Old Musician is an expression of my father, and Teera of me. Teera shares my experience of having a father who disappeared, then returning to Cambodia in hopes of understanding his fate. But the Old Musician also shares my experience of helplessness in witnessing the demise of a loved one, as well as a sense of responsibility, and a feeling of guilt at having survived. So there’s something of me in each.

The characters in Music of the Ghosts and the choices they make are imagined, but the questions they confront are ones I also ask myself. Like Teera, I’ve never stopped seeking my father. I find echoes of him everywhere. When I see an old man in Cambodia, there’s a throbbing tenderness I feel. “What would my father be like if he were alive?” I ask. “How would he have aged? What would he be feeling?”

And of course I’ve spent time with musicians, many of them wounded and blind, and with former soldiers on both sides. So, in a sense, many years of questioning have played a part in shaping the character of the Old Musician.

The Punch: “The dissolution of home requires only walking away, a single flight across the borders, but finding it again takes a lifetime of returning,” you write about Suteera’s choice to stay in Cambodia. Is she finally home, having found love in the young doctor, Narunn? Is her condition — embodying the two selves — similar to your own?

Vaddey Ratner: What Teera learns, and what I have learned through my own experience, is that the tangible home with walls and a roof can be razed, invaded, burned down, abandoned in a flash. But the home that you end up finding, wherever you go, begins long before you lay the first brick or raise the first beam. It’s the home that exists inside of you. Home is not an immovable place. The journey is the home.

Teera found a home in America because she carried within her the memory of a home she’d known in her childhood that she was intent on recreating. And when she returned to Cambodia, similarly, she brought with her that possibility. It’s not because she finds Narunn that she is able to make a home. Rather, it’s through rekindling a sense of home — of belonging — that she is able to love again.

(This is the concluding instalment of a two-part interview. The first part appeared in the June issue of The Punch)

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated