Maite, one of the novel’s two main characters, is a secretary who finds solace in a romantic graphic novel to stop herself from being consumed by loneliness. This changes when Leonora, her friendly neighbor, asks her for a favor: to watch her cat for a couple of days

Routines provide meaning, that’s what Maite believed; therefore she tried to stick to her own patterns. Monday through Friday routines were fairly easy since work dictated her behavior. The weekends, however, were wide open. There were plenty of chances to flounder, to sink into tedium.

Saturdays she got up an hour later than usual, fixed herself a cup of coffee, and drank it in the company of her parakeet. Around eleven she stepped out to buy the groceries at the tianguis that popped up in a nearby park. There she ate a bite at one of the food stands before dragging her market bag, now filled with vegetables and fruit, back home and buying a newspaper.

That day, however, she hurried her purchases, eager to return to the apartment building. She had spent half the night awake, imagining what her neighbor’s apartment would look like. She could have headed there at the crack of dawn, but she knew how much better it was to stretch out the moment, to let it linger on the palate. As she shopped she wondered about the color of the drapes, the type of furniture she’d find. Between the stalls with ripe bananas and tomatoes, she daydreamed.

After tucking away the groceries, she finally allowed herself the chance to turn the key and walk into Leonora’s apartment, slowly closing the door behind her. She absorbed the place, just standing in the living room, her hands pressed against her stomach.

The curtains were blue, made of denim, and they were drawn closed. Maite flicked on a light. A paper lampshade bathed the furniture with a soft, yellow glow. Leonora had less furniture than Maite, but she could tell it was of a better quality than her own. In a corner there was a peacock rattan chair piled with canvases and the couch was covered with a long, tasseled cloth stamped with a butterfly pattern. A low table and two couches served as the dining room. Canvases were also propped against the walls.

Maite looked at the paintings and found them dull: splashes of red with no possible meaning. She was more interested by the photos on a shelf. Leonora and her friends appeared in a variety of poses. There was one shot where she was draped over a man’s lap, a cigarette in her hand, her head thrown back. Maite stared long and hard at that photo, lingering on the man’s handsome face.

A fat tabby rubbed against Maite’s legs, and she shooed it away, irritated by the animal. She wished to finish exploring before get-ting down to the mundane tasks of feeding the animal and cleaning up its shit.

She went into the bedroom and saw that Leonora kept her mattress on the floor. The red silk bedsheets were crumpled and balled up in the center of the bed, and on the floor there was an ashtray. There was booze too, bottles of expensive wine, and a pair of dirty glasses forgotten in a corner. A ceramic Buddha and a plate with half-burnt incense sticks had been arranged atop a pile of books, but for all the Bohemian décor you could smell the money. It was visible in a very modern glass-and-brass table, the quality of the glasses and dishes, the finely carved wooden box where Leonora kept colorful pills, a bag filled with marijuana, and another one with mushrooms. Gold bangles and designer sun-glasses were carelessly scattered around the floor, along with cheap bracelets with wooden beads.

The apartment reeked of money and pot, of pricey wine bottles left open and spoiling, souring the air.

Maite riffled through Leonora’s closet, pressing a green velvet jacket against her waist and glancing at the tall mirror with a silver frame leaning against the wall. A long, cream dress with embroidered flowers, completely unlike anything Maite owned, mesmerized her, and she also pressed that against her body, sliding her hands across the delicate fabric. She looked at the label and decided it must command an exorbitant price. But she couldn’t take clothes. Once she had stolen an earring from a tenant on the second floor, but only one, so that the woman would think she had simply misplaced it. Clothes and jewelry were too conspicuous.

Besides, Leonora and Maite were not the same size.

She put the jacket and the dress back in the closet and walked into the bathroom. Leonora’s bathroom mirror had a white plaster frame with tiny white flowers. Maite grabbed the vintage silver hairbrush resting on the sink and carefully brushed her hair. On a shelf above the toilet she found a jar of face cream and several tubes of lipstick. She tried one on.

It was a gaudy pink, meant for a younger girl. It aged Maite, added years to her face, and she wiped her mouth clean with a Kleenex, disgusted by the sight of it.

She ventured back into the living room and crossed her arms, again looking at Leonora’s pictures, again fixing her eyes on that one shot where the young woman had her head thrown back. The man in the picture was wearing a tie and the corners of his mouth were crooked into a charming smile. Now that was a handsome man. He even looked a bit like Jorge Luis, if Jorge Luis hadn’t been a black-and-white drawing. Leonora might have gone away with that man, or another equally good-looking one, for the weekend. She must be throwing her head back and laughing now.

Maite spun around.

There wasn’t anything she wished to take. Sometimes it was like this, a struggle. Other times she would walk into a room and she would know at once what she wanted. It had to be something personal, something that reminded her of that particular apartment, so that later she might easily conjure the space in her mind.

That was the key.

She had stolen before, stolen from department stores and shabby corner stores, but it had never given her joy. It was a mere compulsion that left her restless and unsatisfied. It had taken her a while to figure out that what she sought was not the object in question, but the thrill of possessing a secret. As if she had been able to peer into the most intimate recesses of a person’s mind and pulled open a hidden compartment.

She’d stolen an old Italian lace fan from the lady with the blind dog on the fifth floor and a broken violin bow from the busy mother on the third floor who was always chasing after one of her children. At one point they’d all asked her to water their plants or feed their goldfish, and she’d slipped into their homes quiet and smiling, trying on their shoes, using their shampoo, eating one of the bonbons in a box. The stolen item was the punctuating mark at the end of her adventure, the flourish on a signature.

The cat was meowing. Maite walked into the kitchen. She found the cat food tins next to the stove and opened one, distractedly dumping it into the cat’s bowl. Leonora had left a cardboard box above the garbage can. She peered inside it, found nothing but old newspapers, and moved the box aside so she could throw the tin away. When she was putting the lid back on the bin she noticed something white in the corner.

Maite moved the garbage can away. It was a small plaster statuette of San Judas Tadeo. It had a crack running down its side, and the girl had taped the bottom of it with yellow masking tape. It was rubbish that she’d forgotten to throw out, like the old newspapers.

Maite held up the statuette, running her fingers over the smooth hair of the saint.

She wrapped the statuette in a newspaper and walked out of the apartment, careful to lock the door and ensure the cat didn’t follow her.

Back in her home she put on music. The Beatles played as she unwrapped her new treasure and placed it in the little brown chest in the bottom drawer of her dresser where she kept all the items she’d stolen. Everything felt right. It had been a good day.

Sunday, she went to the movies, which was a mistake. She preferred romances and comedies, but it seemed to her these were in small supply these days. She wound up watching a Japanese action film as a couple next to her kissed each other, oblivious to the world. The popcorn she’d bought tasted stale, and someone smoked in the row in front of her while a samurai faced off against a one-armed foe on the big screen. She shifted in her uncomfortable seat. By the time she stepped out of the theater it was raining, and she crossed her arms and hurried across the street, trying to protect her head with a newspaper but giving up after a few blocks.

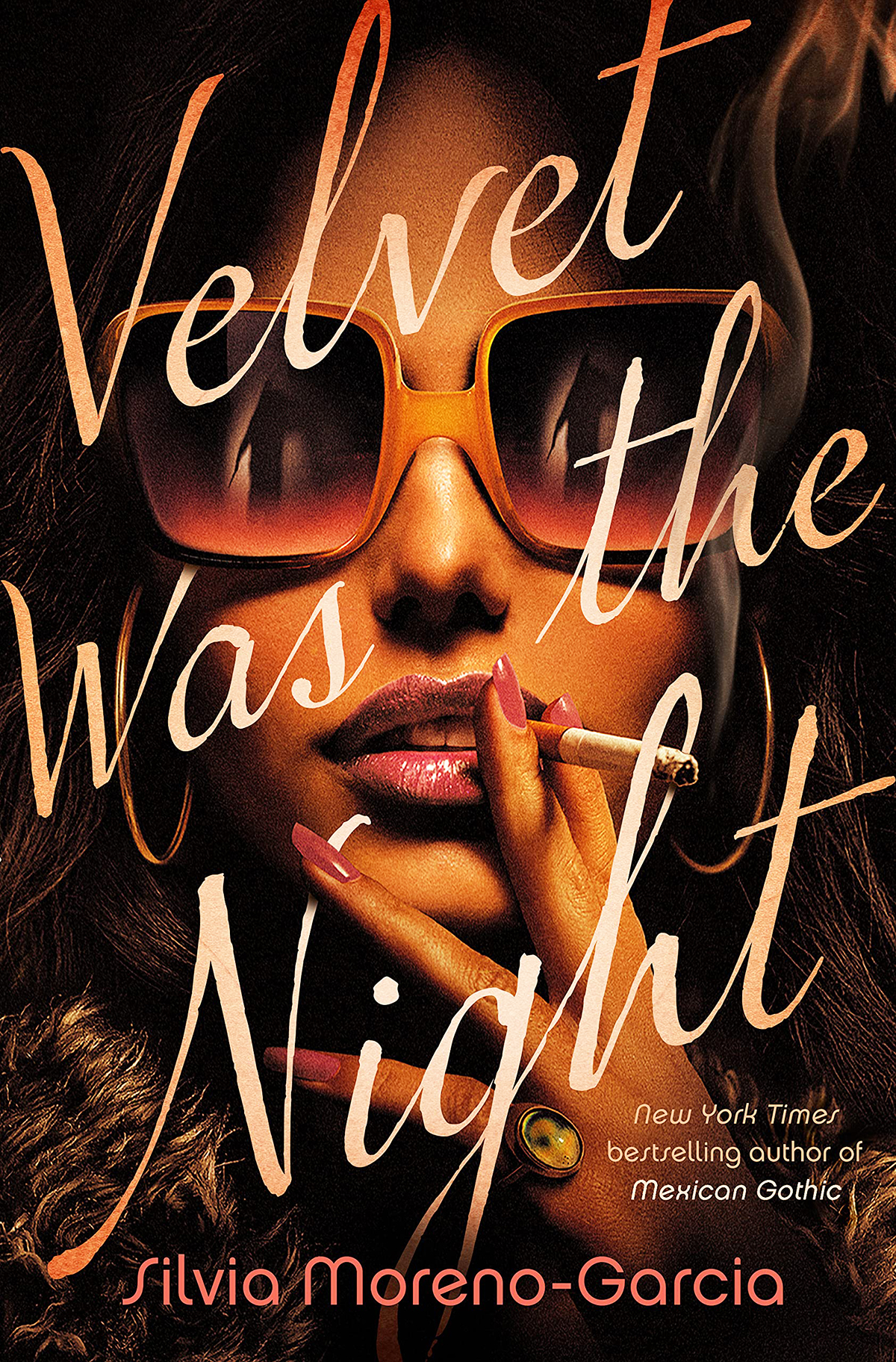

Excerpted with permission from Velvet Was the Night by Silvia Moreno-Garcia, published by Quercus (Hachette India); pp. 384, Rs. 899

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated