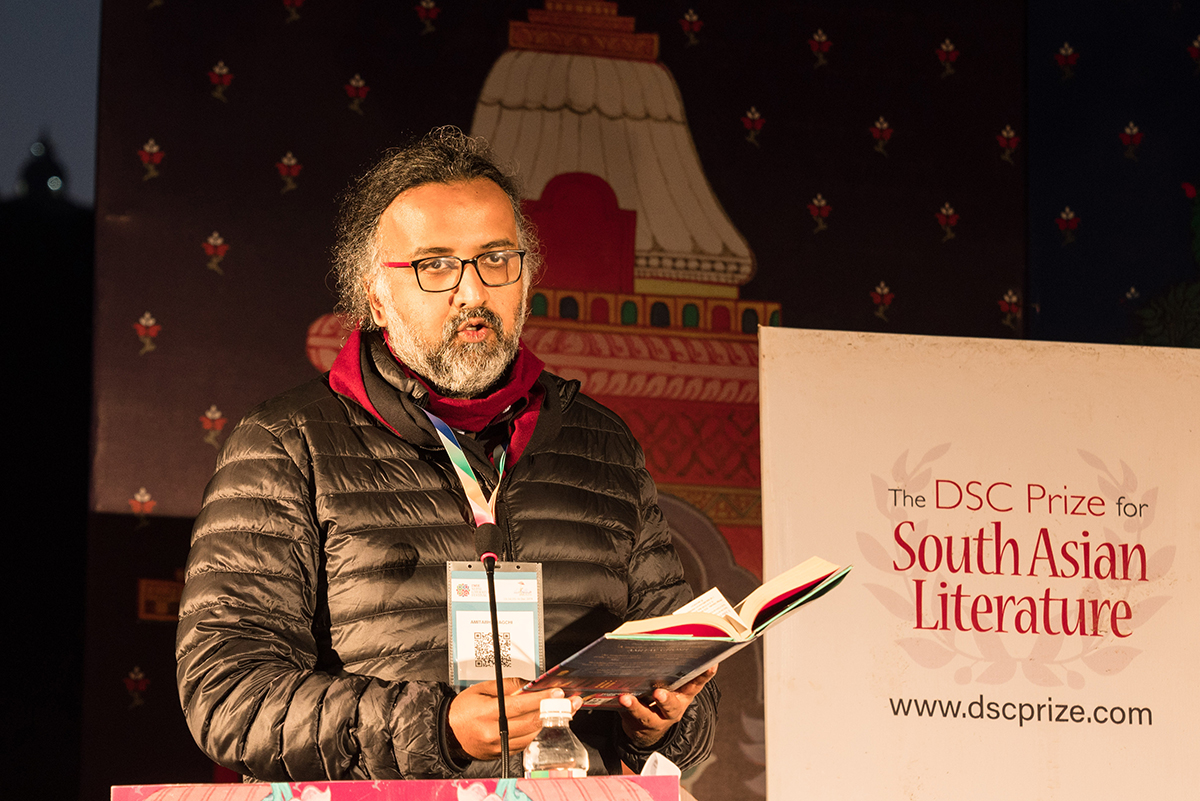

Amitbha Bagchi at the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature ceremony at Nepal Literature Festival in Pokhara, Nepal, in December 2019. Photo courtesy of the DSC Prize

The winner of the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature on his fourth novel about a Hindi novelist who tells the story of India in the early 20th century, a story which speaks to our contemporary fractured realities

Every life is the wreck of a perfect dream. In the case of Vishwanath, the protagonist of Delhi-based author Amitabha Bagchi’s fourth novel, Half the Night is Gone (Juggernaut Books, 2018), it is the same. Spurred by the loss of his son in a car accident, Vishwanath, a Hindi novelist, sets out to write — after a long dry spell — a novel set in the household of a wealthy businessman, Lala Motichand, in the early 20th century, revolving around his three sons — “self-confident Dinanath, the true heir to Motichand’s mercantile temperament; lonely Diwanchand, uninterested in business and steeped in poetry; and illegitimate Makhan Lal, a Marx-loving schoolteacher relegated to the periphery of his father s life.” As he reflects on his life, Vishwanath, the son of a cook for a rich sethji, also tells the story of the lala’s personal servant, Mange Ram, and his son, Parsadi. With the demise of the lala looming in the near future, the story puts the spotlight on the notions of fatherhood and brotherhood, love and loyalty, and poetry. As the event of his demise unfolds in the devotional landscape of Ramcharitmanas, Vishwanath finds himself seeking to make sense of an emerging new India in the first half of the 20th century.

Reading the novel, which won the 2019 DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, in the early 21st century, you’d see how well the echoes of its ideas on religion, literature and society speak to our fractured times. Bagchi, by telling his story through the voice of a novelist, is able to achieve something utterly remarkable in the novel, which brims with life, even though it’s steeped in mortality. Lurking behind the acts of piety woven into the narrative, there is a great deal of poetry — couplets that capture life in a manner only they can. The writer of Bagchi’s imagination is a character who wins your heart early on in the novel by the honest assessment of his life, and his perception of the world around him. In a 2008 letter, with which the novel begins, he writes to his publisher, Sarvesh Kumar of SK Prakashan, he talks about how hard he tried to “capture the entirety of our lives and this world that seduces us with all it can offer”! He writes: “How easily, how routinely, our lives shrink. How easily do they dwindle and diminish. This process of diminution, this deflation, we do not even notice it until it reaches its logical conclusion. And that conclusion is reached in the moment when we are no longer able to notice it.” In the same letter, in which he terms a writer of fiction as a “professional liar”, he writes: “My attempts to convince myself that I have done something worthwhile with my life are fruitless. The arguments don’t ring true. The writing doesn’t ring true. The praise doesn’t ring true. Nothing rings true.”

As a writer, Bagchi has been interested in the lives of individuals caught in the everyday rigmarole of domesticity. He seems to be quite at home while writing about the householders. Like his previous three, this novel, too, brings that element to the fore. His characters seem to scratch the surface of realities around them in order to arrive at the meaning of their lives. Bagchi’s characters seem to be engaged in some sort of conversation with themselves. In an interview, he says that he tries “to enter into the character’s consciousness, try to feel what they feel and guess how they will respond to situations as they arise”. Characters generally appear to him first as images or as located histories. “Sometimes, I feel as if that first inkling of the character contains most of the character’s aspects already and the further fleshing out is more like a revelation of the possibilities rather than a creation,” says Bagchi, adding that the process of entering the skin of a fictional individual is one of the fundamental aspects of fiction writing. “In fact, you could say that is one of the constitutive aspects of fiction writing,” he says.

Excerpts from an interview:

Shireen Quadri: In Half the Night is Gone, did you set out to write the “Great Indian Novel”? How much of the novel is shaped by your appreciation of the writing tradition in India, especially those in languages other than English?

Amitabha Bagchi: It was not at all my intention to write the “Great Indian Novel”, nor do I believe that such a thing should be attempted. I started out with the idea of two brothers and with an image of a pujari who later transformed into a kathavachak, i.e., an expounder of the Ramcharitmanas of Tulsidas. As I went along, many of the things I had been reading over the last decade or two kept finding their way in. At first, it feels like serendipity that something you once read somewhere appears to be an apt reference for a particular point in the book. Then, with hindsight, you realise that the work takes a particular shape so that it can accommodate the things you have read that resonate most with you. So, I think it is correct to say that the project was shaped by my readings over the last so many years, most of which happened to be of Hindi prose and Urdu poetry.

Shireen Quadri: There are two parallel narratives: the generational history of a patriarchal family of lalas, and the letters written by writer Vishwanath looking back at his life in his sunset years to the girlfriend of his son, and his publisher. Was this parallel aimed at capturing India’s journey to modernity even as it continues to hark back to traditions?

Amitabha Bagchi: Whether this parallel captures India’s journey or not is for readers and critics to decide. I don’t think that works that set out to achieve such goals are likely to succeed as novels. My own reason for this parallel structure was different, more practical in some sense. When I started to read the Ramcharitmanas and thought about making it a leitmotif of the book, I felt daunted at the prospect. I felt, rightly or wrongly, that an English-speaking person such as myself couldn’t lay claim to such a text. So I borrowed the idea of the novelist writing a novel from Amritlal Nagar who used this device in Amrit aur Vish. The novelist Vishwanath came to me that way. Being a Hindi novelist, I felt, he could easily claim a major work of the Hindi canon in a way that I couldn’t. This was the practical reason for the parallel structure. Once I had taken it on, it opened many possibilities for me, possibilities that I later realised I had been wanting to explore. But those were writer’s possibilities. What interpretive possibilities it opens up is for readers and critics to say.

Amitabha Bagchi, winner of the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature 2019, receives the trophy from Pradeep Gyawali, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nepal, as jury chair Harish Trivedi and Surina Narula, founder of the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, look on. Photo: DSC Prize for South Asian Literature

Shireen Quadri: Half the Night is Gone also reflects on the ties between brothers, and expounds on filial relations. This intersects both the narratives — one, featuring Lala Motichand and his family, servants like Mange Ram, and the Hindi writer, Vishwanath. Was exploring these relationship within the microcosms of the two family stories part of the germination of the novel?

Amitabha Bagchi: As I recall, the notion of brothers was there in some of the earliest thoughts I had about this book. I vaguely remember that I had some ideas of doing a kind of rewrite of the Ramayan and organising it around two brothers. Those ideas morphed over time to become what you see today. However, the idea of having a story within a story and more than one set of brothers came later.

Shireen Quadri: Since Ramayan was your starting point, did you have to build constructs of exile and the duties of a husband and a wife women into the narrative?

Amitabha Bagchi: No, the story wasn’t dictated by the frame past a point. Much of my own struggles with gender related issues in my writing went in to the process of shaping the women characters. Also the setting and time suggested certain things, as did my reading of poets like Mahadevi Verma. The inner lives of at least two of the women characters are related to Mahadevi Verma’s poetry, either in alignment or in opposition, and the poetry of some other Chhayavaadi (era of neo-romanticism in Hindi literature, particularly Hindi poetry, 1922–1938, that was marked by an upsurge of romantic and humanist content) poets.

Shireen Quadri: It’s a deeply contemplative (ponderous, to steal the word of your writer) novel that is rooted in the ideas of birth, evolution and death, and captures the life cycle of humans, as well the journey of a secular country that sees its descent into divisive politics. How long has this novel traveled with you?

Amitabha Bagchi: In retrospect, it feels like it has been with me for a long time but that is only because many of the elements, like the Ram story or Urdu poetry or the Delhi setting amongst others, are things I have been carrying for over two decades now. However, if you had told me ten or twelve years ago that I would write a book like this I don't think I would have believed you.

Shireen Quadri: Vishwanath, the writer in the novel, seems to be concerned with the depth of feeling religion evokes in people, and how it’s channeled for political gain. How do you make sense of the discourse around religion and politics today?

Amitabha Bagchi: Vishwanath feels, like many other do, that religion has been heavily politicised to a dangerous extent. Of course neither is the politicisation or religion new, nor are the dangers associated with it. They reappear in every age, sambhavami yuge yuge. I don’t necessarily try to make sense of this discourse in the book. Instead, I explore an alternate conception of religion as something that gives strength and succour to people. It may be a quixotic response to the poisonous rhetoric surrounding religion in the political space, but I don’t feel that politics should be allowed to exert such a totalising claim on religion. I feel that which is good, that which speaks to what is noble in human beings, should also get a share.

Shireen Quadri: While literature, as Vishwanath learns, doesn’t arrest the movement of history since it perhaps works on one person at a time. What are some of the books of the 20th century that you found managed to capture the movement of history very well?

Amitabha Bagchi: I have two personal favourites: Zindaginama (1993) by Krishna Sobti and Delhi (1990) by Khushwant Singh. Phanishwar Nath Renu’s Maila Aanchal (1954) and Qurratulain Hyder’s Aag ka Darya (1959) are also high on the list.

Shireen Quadri: The other Hindi novels and writers you give a nod to in the book, like Srilal Suklal, captured their eras brilliantly in some of their works. Do you think today’s literature, especially those from the subcontinent, is the harbinger of any change?

Amitabha Bagchi: It’s difficult to say. When you situate literary production within the attention economy, it simultaneously increases its power by extending its reach and weakens it be reducing the depth to which its readers contemplate it. Does that increase or reduce the potency of literature as an agent for change? I don’t know.

Shireen Quadri: There is a lot of influence of Urdu poetry, and you intersperse the novel with the poetry by Munir Niazi, Allam Iqbal, Bashir Badr, Dushyant, et al. Tell us about your engagement with Urdu, especially poetry.

Amitabha Bagchi: That’s a very general question and to answer it in all its aspects is difficult. So, I’ll just summarise how I discovered Urdu poetry and what channels enabled a deeper connection. The engagement began with the TV series Ghalib (1988) when I was a child, which continued through the beautiful music Jagjit and Chitra Singh recorded for that show. When I went to the US in my twenties, I made some Pakistani friends who introduced me to poets like Parveen Shakir. In the early days of the internet, a lot of Urdu-speaking expats in the Gulf and the US were putting up shayari and related content and I devoured that. I taught myself Nastaliq which made it possible for me to buy books of poetry which was not available in Devanagari or Roman. Eventually, with the advent of Rekhta and its huge archive and the simultaneous upsurge of mushaira videos on YouTube, my addiction only deepened.

Shireen Quadri: Night and dawn as metaphors seem to be vital to the story. Many earlier writers have used this to compelling effect. Do you think these metaphors are relevant to the India story?

Amitabha Bagchi: I don’t think of concepts like “India story” when I am writing. I am not sure I even know if there is a single story or collection of stories that can be called the “India story.” Definitely, it is true that at key moments in the history of our republic the metaphors of night and dawn have been deployed. Faiz’s famous nazm, Subh-e-Azaadi that talks about a “shab gazida seher” (night-bitten dawn) comes to mind. But it is not my way to approach the narratives of the nation as directly as Faiz did at that time or as many others have done subsequently. The metaphors of night and dawn have many valencies, many modes of creating meaning. That’s what makes them so powerful. If you as a reader can connect them to the narratives of the Indian nation then that valency is also inherent in them.

Shireen Quadri: Tell us something about your approach to characterisation. Most of your characters seem to have jumped into the pages from real life? What does fiction writing mean to you?

Amitabha Bagchi: My approach to characterisation is probably the same as that of other writers: you try to enter into the character’s consciousness, try to feel what they feel and guess how they will respond to situations as they arise. Characters generally appear to me first as images or as located histories. Sometimes, I feel as if that first inkling of the character contains most of the character’s aspects already and the further fleshing out is more like a revelation of the possibilities rather than a creation.

It’s interesting that you paired your question about characterisation with the more general question of what fiction writing means to me. I do feel that the process of entering the skin of a fictional individual is probably one of the fundamental aspects of fiction writing, in fact, you could say that is one of the constitutive aspects of fiction writing.

Shireen Quadri: How do you look at writings in English by some of your contemporaries in India or South Asia? Are there subjects you wish were more highlighted in their writings?

Amitabha Bagchi: If there’s one prescription I believe in it’s that one shouldn’t write by prescription. I wouldn’t like it if someone told me to write more of this or less of that so I don’t hold opinions about what my South Asian contemporaries should or shouldn’t do. In fact, I view it the other way: I see what engages my contemporaries and I try to understand what it says about the times they, and I, live in.

Shireen Quadri: Do you think awards like DSC Prize for South Asian Literature are taking the South Asian literature under a global gaze?

Amitabha Bagchi: The effort seems to be in that direction and that’s a good thing. However, I feel that the global gaze shouldn’t be given too much importance. Writing in English in India, I feel like I am suspended in this intermediate state, a kind of Trishanku state, between the global (which normally means Western) and the local (which normally means writing in Indian languages apart from English). Another metaphor comes to mind: dhobi ka kutta na ghar ka na ghat ka (hard to translate to let’s just say that it’s a crude way of saying “neither here nor there.”) Both directions are important but at the end of the day, it is our primary audience that we must be true to.

For writers, there are two very different things we seek from an audience. One is the money and the prestige that comes with widespread recognition. For these things, Indian English writers look to what you have called the global market. The other kind of thing is a connection, a kind of recognition, and where we seek that depends on the book. Earlier, I wrote a novel called This Place (2013) which was set in America and for that I sought that connection with a US readership but didn’t get it. For Half the Night is Gone, I feel I have been able to connect with English readers in South Asia but what I have been hankering after is the Hindi audience more than the global audience. A translation is ready but it still hasn’t found a publisher. Perhaps the search for connection is destined to remain incomplete. If the recognition the DSC Prize has already conferred on me helps my book find new readerships within South Asia and outside, then I will be very grateful for it.

Editor‘s Note: This story was updated on December 20, 2019

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated