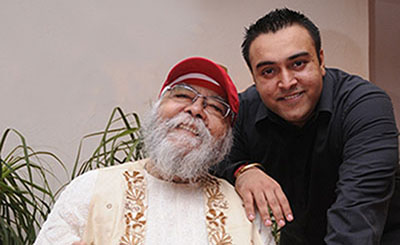

Poet and novelist CP Surendran. Photo: Ravi Mahadevan

Poet and novelist CP Surendran’s fourth novel, One Love and the Many Lives of Osip B (Niyogi Books), assumes the reader’s intelligence. It is the story of Osip Bala Krishnan, a student at a boarding school in Kasauli, who falls in love with his English teacher, Elizabeth. Named after the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam by his Stalinist grandfather — with whom Osip shares a unique mental condition that often causes him to hallucinate incidents of Russia in the mid-20th century — he is determined to find Elizabeth, after she disappears. In the process, Osip unravels the secrets of why his grandfather pretends he cannot remember his past.

Osip’s journey is aided by his friend, Anand, a god-man on the make; Arjun Bedi, an iconoclastic writer disintegrating under harassment allegations; and the corpse of the school priest, which Osip and Anand kidnap to extort seed money for their adventures. Through a clutch of dramatic characters, the plot traces and connects contemporary themes of transgressive relationships, gender politics, nationalism, individual freedom and group rights, fake news, and power. Sad, funny, and insightful, the novel asks: Can a dysfunctional young man survive in a deranged world, our world? Excerpts from an interview:

Padmaja Challakere: Your latest novel, One Love And The Many Lives of Osip B, is about a young man, adrift, in his adventures. It is at once sharply topical and poetic. The novel is poetic not only because of the startling effects of its language, but also because of the economy and precision with which you do dialogue, or engage the emotional and imaginative aspects of love, vulnerability, and the exercise of power. Your characteristic lyrical-satirical style — so distinctively present in your poetry, journalism, and film scripts — is in full play in this novel. I found it to be a crackling read. It is fundamentally unlike anything else you have written. The reader experiences here an intimate knowledge of the personal experiences of the characters; an understanding that renders the text readable at more than one level. Hadal (your third and last novel) is interested in exploring the exercise of absolute power. Can you speak about the arc of your new novel, the change from Hadal to One Love...?

CP Surendran: Hadal is about a young woman from the Maldives arriving in Trivandrum. She has a broken marriage and soon finds herself caught inside the prurient and fecund imagination of a corrupt police officer (Honey Kumar) who, to get sexual favours from her, frames her as a spy come to ferret out the ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation) rocket secrets. It is based on a true incident: but then what is more bizarre than the real? It is a flawed novel in the sense that there are themes I did not fully develop, and toward the end, I was vulnerable to the facile charms of suspense and pace. It is, I think, a well-written novel, but not so grand (as one would be forgiven to expect in its vision of humanity), or a sustained character study. In fact, one of its flaws is that it is not ambitious enough to meet either of those literary standards.

Between Hadal and One Love..., more than seven years have elapsed. The man who finally wrote the last line in One Love... is vastly different — and, I think, diffident, as well as more mortified — from the one who wrote the rather optimistic Hadal. Optimistic in the sense that at some bottom level, good will come off the universal scheme of things. That one must hold onto hope if only for form’s sake. There is no such thought process at work in One Love... This novel is fatalistic — almost.

I am a late bloomer, if at all. A slow learner for sure. All through my school and college, I had vague inklings that I didn’t belong to the class and the subjects taught there. Whose life was this? So, I could not understand a word in most subjects. In retrospect, one could say I was just not interested, too. But it is more than that. It is always more than what it seems, isn’t it? Or less? I think, in many ways, I was dyslexic. Certainly dysnumeric. What I was, was a writer. But it, too, was a vague abstraction at the time, like a shadow ever creeping back under the source-rock as you approached it.

Ah, yes, that bit about blooming.

I am not surprised that the three novels I wrote prior to this (An Iron Harvest, Lost and Found, Hadal) are just a pyrrhic training ground, a violent and time-consuming means to One Love.... I may be doing the right thing here to disown them. A possibility of the eternal sunshine of the spotless mind beckons. One must have the right to forget one’s work, surely, as must one one’s Google profile which in my case is almost criminal, thanks to some of my friends in the journalist community.

As you pointed out, Hadal is about power. It’s about absolute authority (Honey Kumar, the corrupt police officer) in the confined space of a cell dealing with himself and dealing with his victim (Mariam, the tourist-turned-spy). But the victim has no power over the victor. That has changed in One Love..., where the victims are aware of their potential to challenge the victor, on occasion, even unfairly. Also, Hadal is about a situation. In One Love..., the ‘aboutness’ of a situation is secondary. It is what it is. Archibald MacLeish said, a poem doesn’t mean, it is — no matter how unreal, as the hallucinations haunting Osip are: the voices of Mandelstam and Stalin from Russian history, of poet and persecutor, of victim and tormentor.

We know our lives are modes of relationship to power. Only now, in the current phase of history, the group empowerment ideologies end up victimizing, perhaps as collateral, the individual. This ties in with the current democracy of numbers, of big data. The reason why most of us find ourselves constantly in a state of anxiety is that we are increasingly powerless in the face of that abstraction; we have no real control over anything in a world that the crowd or the mob (algorithm) has taken over. I see group rights (the number of likes to a cause) a variation of AL.

The arc from Hadal to One Love... is a broken one, nevertheless. There were times so dark in that period when I, and my family, were subject to organised persecution by groups, accusing me of things which, had they been not caught up in the victimhood wave, would have seen as banter or harmless acts of flirtation, or just intellectual provocations, norms really of another age, in retrospect.

But to turn what happens to you at the deepest level to the material of the imagination is a painful one, and fraught. Painful in the re-living of the trauma, the same thing for the 100th time. Fraught, because in re-rendering that experience, one must take extreme care not to write it with pity. It is all very well to say that one must write what hurts one honestly and clearly. It is just so very difficult. Because the honesty is not to the experience, but to the fictionality of that experience.

As an author, you could sympathise with a character but you could really never console him or her, there cannot be any easy assuagement. In my case, one of the characters, in One Love..., Arjun Bedi, began to assume ominous biographical dimensions, and deeper connections with his protégé, Osip, in the sixth or seventh year of the novel. The broken arc of the novel was somewhat mended, in all truthfulness, when the last word was written, say some six months ago, when I thought the novel now more or less qualified to be abandoned.

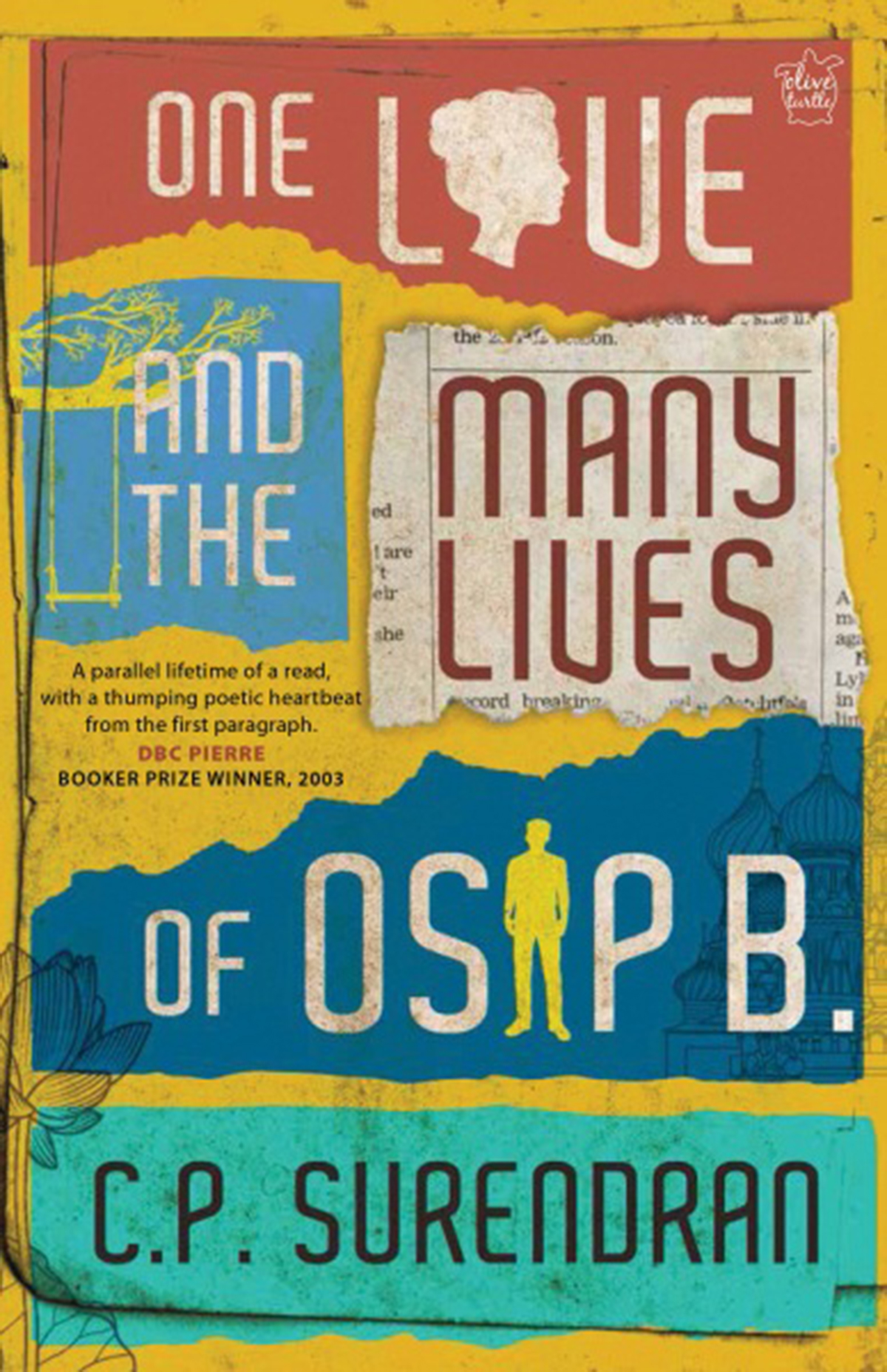

One Love and the Many Lives of Osip B

By C.P. Surendran

Olive Turtle (Niyogi Books)

Rs 695, pp. 372

Padmaja Challakere: The rise and the hardening of Cancel Culture, which views the world through a group oppression, lens and advocates punishment, silencing, or violence against those in error or those “oppressing” is a significant theme in the novel. Your epigraph says: “Victims and their Victims.” Can you elaborate on that? Are Dev and Divya, the group rights activists in the novel, minor comic figures, or do they represent a significantly troubling trend of social-media directed-Wokeness in the world? Arjun Bedi, the iconoclast writer, who is cancelled by his editors, has this to say about group identity and its one-directional belief in the universal rightness of its premises: “Social media, the new world, works on shared disorders... What was the hashtag but a sign of the secrets of a given group? Each in his lunacy hoped another would share what he transmitted, and validated his view.”

CP Surendran: The allegations against Arjun are serious; serious in the sense that these are the times when an allegation is as good as a proven charge. And an apology is as good as an admission. The trial and punishment are carried out by non-state players. There is no due process of law. There is no due process of law because our sense of justice has changed. We want instant justice, even if that justice is pure revenge — that is a lynch mob ethic in operation. The victim is right because he or she is the victim. Does that create victims in its turn? Yes. That’s why the novel is dedicated to ‘victims and their victims.’

Arjun is facing cancellation for life. It is a death sentence by other means. His question is: a word I said, or a touch, out of turn, a joke; are these the most traumatising events in my victim’s life? Haven’t their servants or drivers or uncles or aunts or boyfriends, or husbands done more harm? Why is my word more punishable? Because he is famous. Arjun believes that the rights involved here are those that give existential meaning to the urban elite, a class to which his detractors, Dev and Diya, belong. The couple is not comic at all. They are an essential if a menacing aspect of the program of historic correction. Later in the chapter, losing his ground heavily, Arjun asks if Dev and Diya are doing a book, and would their fame and followers as campaigners help them to promote their book? This turns out to be true. But his point and his vindication that striving for fame (a kind of social validation?), like hunger, sex, and power, has become a fourth definitive drive in human affairs is not of much consequence, as fate and society have already decided that he must, well, be no more. He has transgressed. And must be punished. The new age demands it. At great times of upheaval, society demands human sacrifices. That it is bloodless, virtual as social media is, makes it no less final than an execution.

Padmaja Challakere: I am astounded by the seven-year-long revision and how it has transformed the novel for your readers. The revisions you made gave voice to characters — characters like Gloria (Osip’s long-suffering grandmother) and Kris (Elizabeth’s elderly lover in England) — gave them the freedom to evolve, and the revision increased causality in the novel. What was it like for you: this labour of revision? What changed for you, and for the novel in its journey through the publishing world? The characters and human interactions in the novel-how did revision transform them? I found myself having many sympathies even with characters I did not like —Aanand, Osip’s roommate who grows up to become a fake spiritual guru.

CP Surendran: This is probably one of the most rejected novels of the decade. Not just because of the cancellation culture in vogue. But also because this novel was looking for a form for a long time. Naturally, no publisher would touch it. No publisher in these times has the patience to shape a draft. And why should they? There is a lot of good writing happening. Why persist with potentialities? It is quite astounding that for the longest time only the carpenter could see the carving in the wood. For the others, it was just a block without shape. Then the cancellation thing kicked in, and then it was free for all. To desperate pleas, still monosyllabic yet Delphic utterances were given. Friends dropped out. One agent friend kindly intimated: “no one wants to read you.” My challenge was how to spin the hell that was happening to me into a polestar leading me out to creative freedom; turn life into fiction.

I knew the plot was mostly there. It was the characters that were a problem. At least three of the main characters, including the protagonist, are not people who do naturally good things. At least two of those three are nearly criminally self-indulgent. One of the challenges I constantly face in writing fiction is self-identification with one’s characters. It is an occupational hazard. The truly great writers, like Tolstoy or Dostoyevsky or a modern great like Ford Maddox Ford (notably, The Good Soldier), have a way of putting their characters in such extreme situations that they may be truly said to be sadistic. Like flies to wanton boys etc. I believe one of the functions of such situating of the characters is that it effects a distancing from their progenitors. It is a rather Godly thing to do. Who else but a Tolstoy would push lovely Anna under a train without batting an eyelid? Place Eve close to the apple and watch the fun, kind of. One learns to be tough on one’s characters finally and perhaps with great reluctance. And if and when one succeeds, one is no longer looking for justification for oneself. You stop using your characters as an alibi, even if your novel is somewhat autobiographical.

The thing about characterisation, I learned the hard way, is that a certain justness in relation to each one’s perspective, even if it’s self-serving and ‘wrong’, (for the character in relation to the rest) is very important in the distribution of a novel’s moral burden. One needn’t labour at it, but the way a character looks at the world is pretty much how he shapes it. That’s why he or she is constantly surprised when the world turns around and kicks his backside: I am so right, I was just being myself, why is everybody so mean to me? Because we are unable to step outside ourselves and look at the world.

It’s my guess that group rights are a way of bridging the gulf between the individual and the social reality. We have so many prescriptions to behave simply because the group is saying that that is the best way, that ‘we’ are helping ‘you’ to a less painful life, just behave the way we, the group, want. It is well-intentioned. Only, its collateral damage is the elimination of individualism — for the larger good.

You mentioned Aanand. Unlike Osip, Aanand blends with the group. Aanand is Osip’s spiritual twin. Only, he succeeds where Osip fails. He is not a bad man at all. In fact, he tries to help Osip, except in one crisis where his own skin is in question (over the incident of kidnapping of the school priest’s corpse for ransom).

Aanand’s strength is that he is not troubled by existential demands as Osip is. He sees things and people as a game. A game that can be played and won. Osip is terrified that he will become part of the game, that his individual essence would be eroded, that the poet in him will end up as the prosecutor. His instability, or depression, or mood swings, do not help him either. Osip is aware he is dysfunctional. But he finds the world around him worse, deranged. Surely, there really is no explanation for poverty, war, and murderous violence over ideas like nationality, etc? We have the means to eliminate most of our sufferings. But we won’t. Because then the social and political and financial world that we have built for ourselves will have no meaning. God never meant us to suffer so much, did he? He put us out of the Garden. But who built the cinema hall? And the brothel? And the banks? It is we who have decided to fashion this unforgiving world, whose only redemption seems to me, well, the ghee-dosa. How does one make one’s way forward in this all-pervasive mess? Or, indeed, backward?

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

Great article, enjoyed every bit of it... I am glad that I could contribute a picture of his to this column. Wish it could have been more dedicated to its original tone and contrast while being processed for this web article.

RAVI MAHADEVAN

Aug 6, 2021 at 21:21