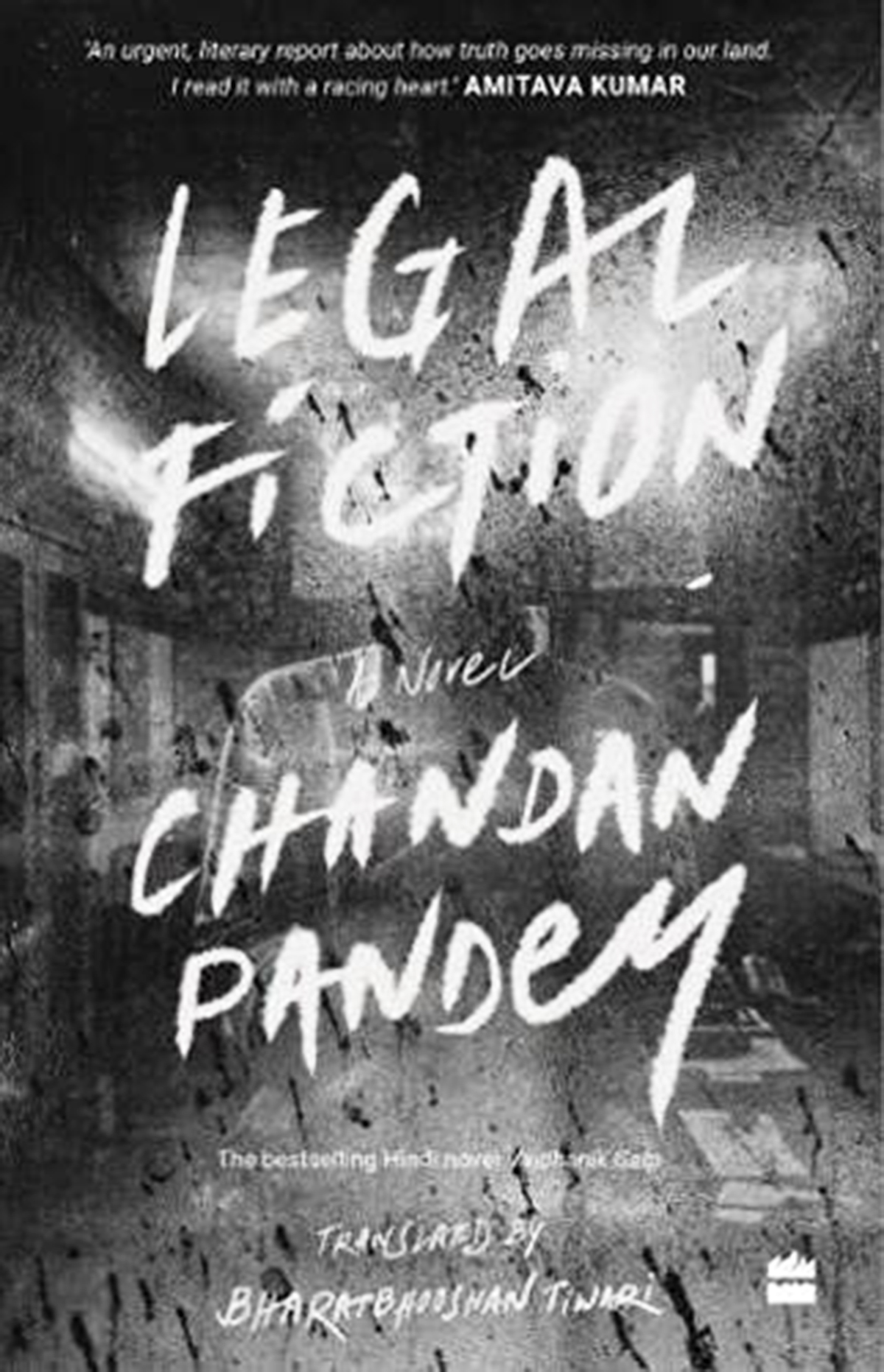

Chandan Pandey, author of Legal Fiction, a potent political novel. Photo courtesy of the author

In his Kafkaesque new novel, translated from the Hindi original (Vaidhanik Galp) by Bharatbhooshan Tiwari, Pandey shows us the true picture of contemporary India, where the right-wing narratives like ‘love jihad’, designed to foster hatred towards Muslims, have reached a fever pitch

In Legal Fiction, Chandan Pandey’s latest novel, a writer from Delhi enters the mad, sprawling land of Noma as a timid, clueless onlooker and leaves with his view of the world in a million pieces, but not before he has unearthed Mayakovsky’s poems living on in dusty secrecy, become the object of perverse wonderment, and scraped the grisly underbelly of small-town realpolitik. The writer, Arjun Kumar, is a caricature of the utterly mundane in all of us: he objects to PDA, doesn’t forget an old romantic interest, and wallows in self-pity, but he also surrounds himself with the drying pages of strangers’ thoughts and is out of step with townsfolk marching to a sinister drumbeat, as people disappear like flies and the only egress is unfriskily giving up the strings to your own self. In Legal Fiction, translated from the Hindi original, Vaidhanik Galp (Rajkamal, 2020) by Bharatbhooshan Tiwari, Pandey is in total command of his craft as he describes the system with a capital S. He writes often, sometimes not in print, about the life and times of a country headed somewhere. Pandey describes himself as a “non-writing writer”. He is the author of three short-story collections and one novel in Hindi. He has won the Bharatiya Jnanpith’s Navlekhan Award, the Shailesh Matiani Katha Puraskar, and is a recipient of the Krishna Baldev Vaid Fellowship.

Serving the role of an urgent report — as a blurb is prompt to notice — Legal Fiction is riveting and contemporary.

Excerpts from an interview:

Utkarsh Mani Tripathi: The timing of Legal Fiction, as you mentioned in an earlier interview, might make it look like it was written on a lark, because of recent news items, but you actually began writing it in the early 2010s. What is your opinion about literature in Hindi and English — is it adequately addressing issues as much as you wished they did?

Chandan Pandey: Perhaps not. Literature is not addressing the issues with which we are concerned here, i.e. mob lynching, at all. The situation is the other way round. Literature as an institution, and I include platforms such as media houses here, is trying to muffle the voices which are actually raising such concerns through their literary works. My publicist told me many media houses had refused to carry reviews or articles on Legal Fiction because of its subject. Such things are disappointing; the least for me, though. Personally, I treat it as a motivation [to raise the issues that bother me]. But the whole publishing business, as it is, is heavily dependent on reviews and publicity through media. It may start a feedback loop or a vicious cycle where inadequate publicity will dissuade such voices from writing on these contemporary topics.

Utkarsh Mani Tripathi: Legal Fiction has been favorably compared to Franz Kafka’s works. I believe that has to do with the way the main character seems hapless in the face of the System. Do you see a light somewhere, cliched as it sounds? Are people like Arjun waking up, smelling the coffee?

Chandan Pandey: First of all, I was embarrassed to see those comparisons. But you are right; they must have arisen due to the conditions of the narrator. Had I known such comparisons would be made, I would have tried to write better for Kafka’s sake. (Smiles)

Regarding the second part of the question, I am honestly not seeing it. The light. There may be some issues with my perspective of the world but I am not able to see any improvement, anything getting better, be it the System or the society. For instance, the partition of 1947 had horrendous, heartrending consequences. It has given the right wing a false hope that they can do whatever they want under the sun. . . fiddle with society; in the process, they have started branding minorities as public enemies.

To address the third part of the question, individuals like Arjun may smell the coffee but the point here is to switch that coffee, if you get the drift. I think it can be done only through social change and individuals can add value to it through individual efforts.

Utkarsh Mani Tripathi: Is Kafka a major influence on your work?

Chandan Pandey: I have been an avid reader of Kafka. I’ve read him many times over, mainly his short stories. Two writers I always like to reread are Kafka and Muktibodh. I’m not sure if they’ve had an impact on my writing but if they have, I shall feel blessed.

Legal Fiction

By Chandan Pandey

Translated by Bharatbhooshan Tiwari

Harper Perennial India

pp. 168, Rs 299

Utkarsh Mani Tripathi: Legal Fiction is the first part of The Citizen Trilogy. Tell us more about it. What themes are you going to address?

Chandan Pandey: Mob lynching, the scale of mob lynching, and its impact on society. Then, if possible, I’d embark on a comparative study with respect to events in the past.

Utkarsh Mani Tripathi: On your blog as well as in Legal Fiction, you have expressed disdain for onlookers who encourage hate-mongering by their complicit silence. Why do you think narratives of love jihad are gaining traction? Don’t people realize the politics behind it? Or has politics dehumanised us?

Chandan Pandey: There are people, to be sure, who believe in the narratives of love-jihad, but they are largely those who believe in right wing propaganda and are quite naive otherwise. These are innocent people and minds. At the same time, there are people who are well aware that it is sheer propaganda but still pretend to be just as innocent. These include those who create content that actively spews hate. They have their own agendas to pursue. And, yes, politics has indeed dehumanized us.

Utkarsh Mani Tripathi: The concept of the “image” is interesting. It is visible in the purported affair between Anasuya and Arjun, between Janaki and Rafique: a constructed narrative. People believe in images easily. Even the writer constructs an image of a village based on imagination. How do you see this playing out in literature (this is also the question Arjun is asked at a point in the book)?

Chandan Pandey: Tough one. First of all, one needs to agree that literature has a certain role to play in society. Coming to terms with it is difficult. But once you agree, you have to wage a war against all evils haranguing and flourishing in our society. The role of ‘images’ is one such thing. More than a few social evils are spread through constructed images. Those evils can be countered through a counter-narrative or a counter-image, or both.

The images in case of Anusuya and Arjun are the reference points. Explainers, sort of. Without them the novel might have to spend pages and pages to show their relationship and its development.

Utkarsh Mani Tripathi: The rule of law and the rule of land: tell us more?

Chandan Pandey: The rule of law is never in isolation; it is always impacted by the rule of land. There are geographies where people feel positively hurt if you convince them to follow the rule of law. They have always enjoyed the privileges of the rule of land and they want that to continue. As a country and society we have so much to do to usher a rule of law exclusively. We saw the Delhi riots. The Keepers of the Law suddenly took over the role of Keeper of the Rule of Land, to ghastly results.

Utkarsh Mani Tripathi: The last part of the book seems to be a message to the readers to marshall a surge of change, even if they are the first and only ones to do so. Do you think that is possible in our highly selfish lives?

Chandan Pandey: There is no other way, to be completely frank. Dramatically enough, you fight or you perish. One thing I’d say is that in a good society, fighting for one’s own self is not a selfish act. We should understand that anyone would fight back if they feel attacked; this feeling, it needs to be understood better. If your training in the ways of society is good enough, you’d feel attacked when your society is threatened. And that threat will lead you to regroup, socialize and give it unalloyed hell.

Utkarsh Mani Tripathi: You have won quite a few literary awards for your books in Hindi. One often thinks about English language prizes such as the Booker or indeed the Pulitzer — winning one of those is an instant shot at books selling out like hot pies. Do you see that happening for Hindi literature?

Chandan Pandey: Awards don’t get much attention in the Hindi literary scene. In Hindi, the quality of writing gets noticed early on. Readers have their own pet peeves and fetishes, favourites, and are hardly affected by awards or other publicity. Their personal preferences sprout from literary magazines, which, though small in circulation, often generate good readership.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

thank you for the book discussion. i am searching books on lynching. I am going to collect The Legal Fiction for reading and writing. Congratulations!

ABU SIDDIK

Feb 25, 2023 at 20:02