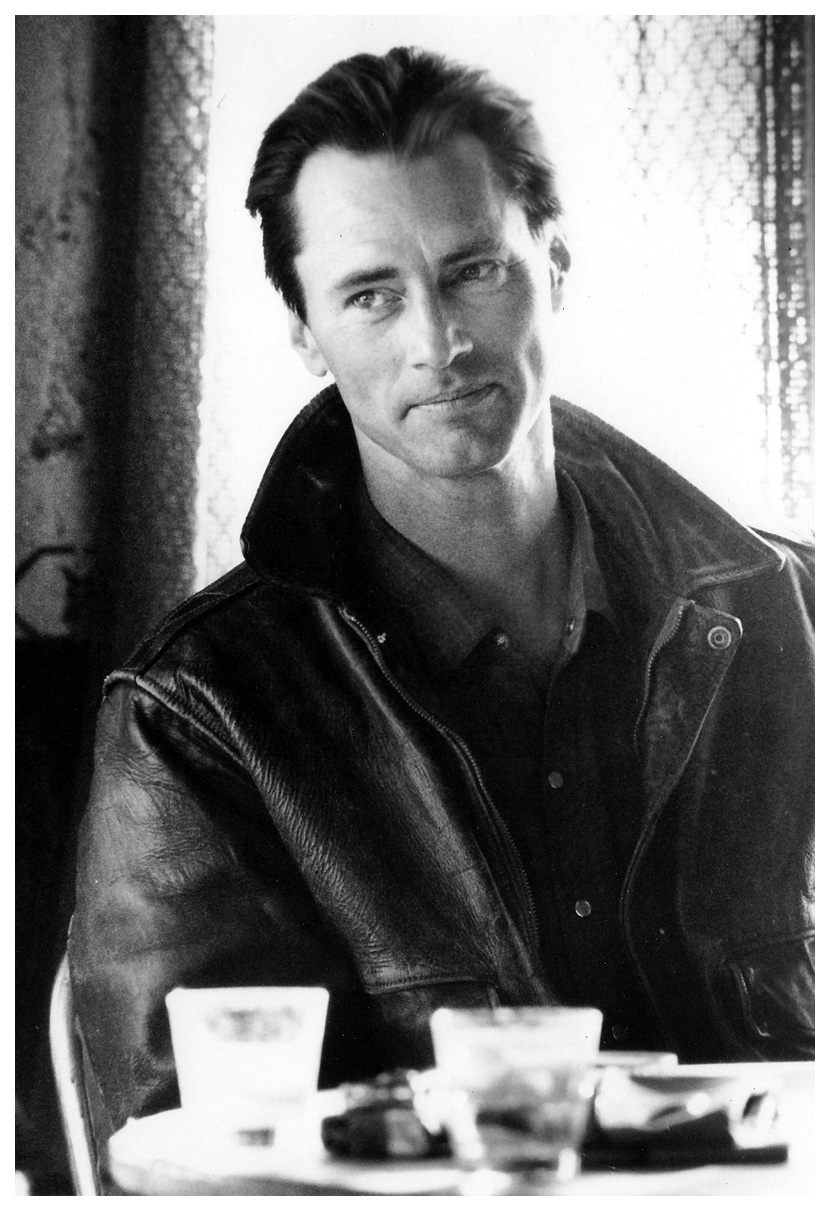

John J. Winters. Photo: Karen Callan

John J. Winters, author of Sam Shepard: A Life, on the gap between the image of the man and the man himself

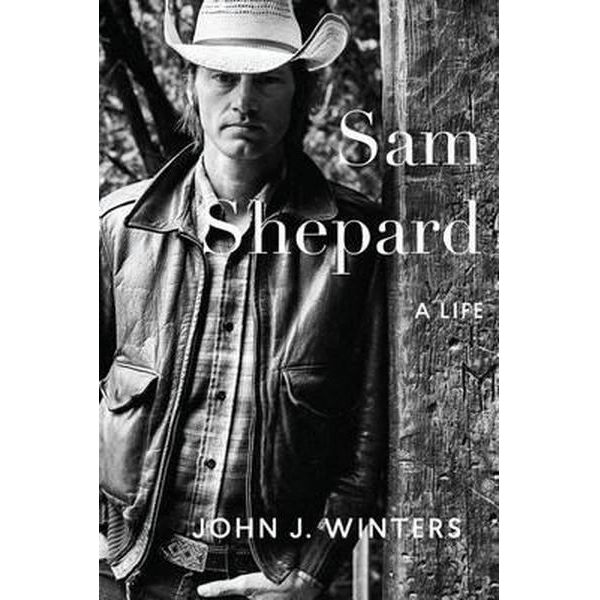

In Sam Shepard: A Life (Counterpoint Press, 2017), veteran journalist, critic and academic John J. Winters attempts, with great success, to put Sam Shepard in sharper focus. Winters says it was a “daunting subject” to undertake as a biographer. The reason: the many artistic fields in which Shepard triumphed, with a wide array of plays, short stories, and screenplays. “His acting career on its own is impressive enough to warrant a biography,” he says. Winters says he wanted to write about Shepard’s life and work, and to find the “connections between the two”. He says: “It was never meant to be an academic study of his work.” Shepard, says Winters, will be remembered as a singularly original playwright, and as a much-beloved actor. “The quintet of family plays — Curse of the Starving Class, Buried Child, True West, Fool for Love and A Lie of the Mind — guarantee his place in the pantheon of great American playwrights. As an actor, The Right Stuff, Days of Heaven, Voyager, Blackthorn and a handful of other roles will secure his place as an actor who brought something special and powerful to the screen,” says the biographer.

Winters writes that Shepard was not the “intrepid artist-cowboy of popular imagination”, but a man who, despite all his accomplishments, found himself “caught in the same existential bind” as most of us. He had admitted to feeling like an “imposter”. He had feelings of “inferiority” and “shortcomings” filled with “un-nameable fears and anxieties, lostness.”

Sam Shepard: A Life focuses on the gap between his image and the man himself. Winters says Shepard was a seeker who sought the answers to the biggest — and most basic — questions. Excerpts from an interview:

THE PUNCH: Sam Shepard deconstructed the American zeitgeist in a distinctly charged language littered with vernacular expressions and suffused with“existential dread”. He was someone credited with reimagining the mythic American archetypes. In your wonderful Preface to his biography (Sam Shepard: A Life, Counterpoint, 2017), you write that chronicling the life story of Shepard means “tracking a moving target, as he’s ranged artistically and geographically all over the map inwhat his friend the film director Michael Almereyda refers to as Shepard’s ‘sweeping road movie’ of a life.” Could you describe the challenges before you as a biographer when you set out to chronicle the story of such a subject?

JOHN J. WINTERS: Sam Shepard was a daunting subject to undertake as a biographer, simply due to the many artistic fields in which he triumphed, and his amazing output of plays, short stories, and screenplays. And then there’s his acting career, which on its own is impressive enough to warrant a biography. In fact, as I was beginning my work on the Shepard book I had second thoughts, almost changing subjects to a novelist who was “merely” a writer. But I’m glad I stayed with Sam. The trick was to know what plays to devote time and space to, and what films to focus on. I like to say the biography is comprehensive, but in fact, dozens of his film roles do not get mentioned in my book. These were movies that weren’t particularly special, and in which Shepard was involved because he needed the money. I mean, if I spent a page on films like The Accidental Husband, readers would have rightly tossed the book across the room.

THE PUNCH: Could you recount the transformation of Steve Rogers who, when he landed in New York, in the 1960s, had to sell a pint of blood to get a cheeseburger, into what he eventually made of himself and became Sam Shepard?

JOHN J. WINTERS: Shepard arrived in New York City knowing he wanted to do something creative. He’d done some acting in school, but hated auditioning. He would have jumped at the chance to join an up-and-coming band but had left his drums back home in California and couldn’t afford a few set. Writing was something he could do anywhere, and he romanticized the idea of sitting in a Greenwich Village café with a pen and pad of paper. An important connection was someone he’d known a bit from high school back in California, Charlies Mingus III, son of the legendary jazzman. Through this connection, Shepard found a run-down apartment and, most important, a job bussing tables at the legendary jazz club, The Village Gate. The members of the club’s staff had their own artistic ambitions, including the maître’ d’, Ralph Cook. It was Cook who worked out an arrangement with a nearby church, St. Mark’s in-the-Bowery, to use its parish hall to stage plays. When Cook asked around the Village Gate if anyone had a play they’d written, Shepard did. Cook directed, and the actors came from the ranks of the Village Gate’s staff. He was on his way.

THE PUNCH: A playwright. A musician. An actor. Shepard was a man with many talents. In what arena do you think he excelled in and has left indelible imprints behind? What parts of his legacy we must treasure?

JOHN J. WINTERS: He will be remembered as a singularly original playwright, and as a much-beloved actor. The quintet of family plays — Curse of the Starving Class, Buried Child, True West, Fool for Love and A Lie of the Mind — guarantee his place in the pantheon of great American playwrights. As an actor, The Right Stuff, Days of Heaven, Voyager, Blackthorn and a handful of other roles will secure his place as an actor who brought something special and powerful to the screen.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated