Anuradha Roy. Photo: Rukun Advani

I want readers to feel and think and be immersed in its world, says Anuradha Roy of her new novel, All The Lives We Never Lived, a quiet examination of the myriad fissures of India

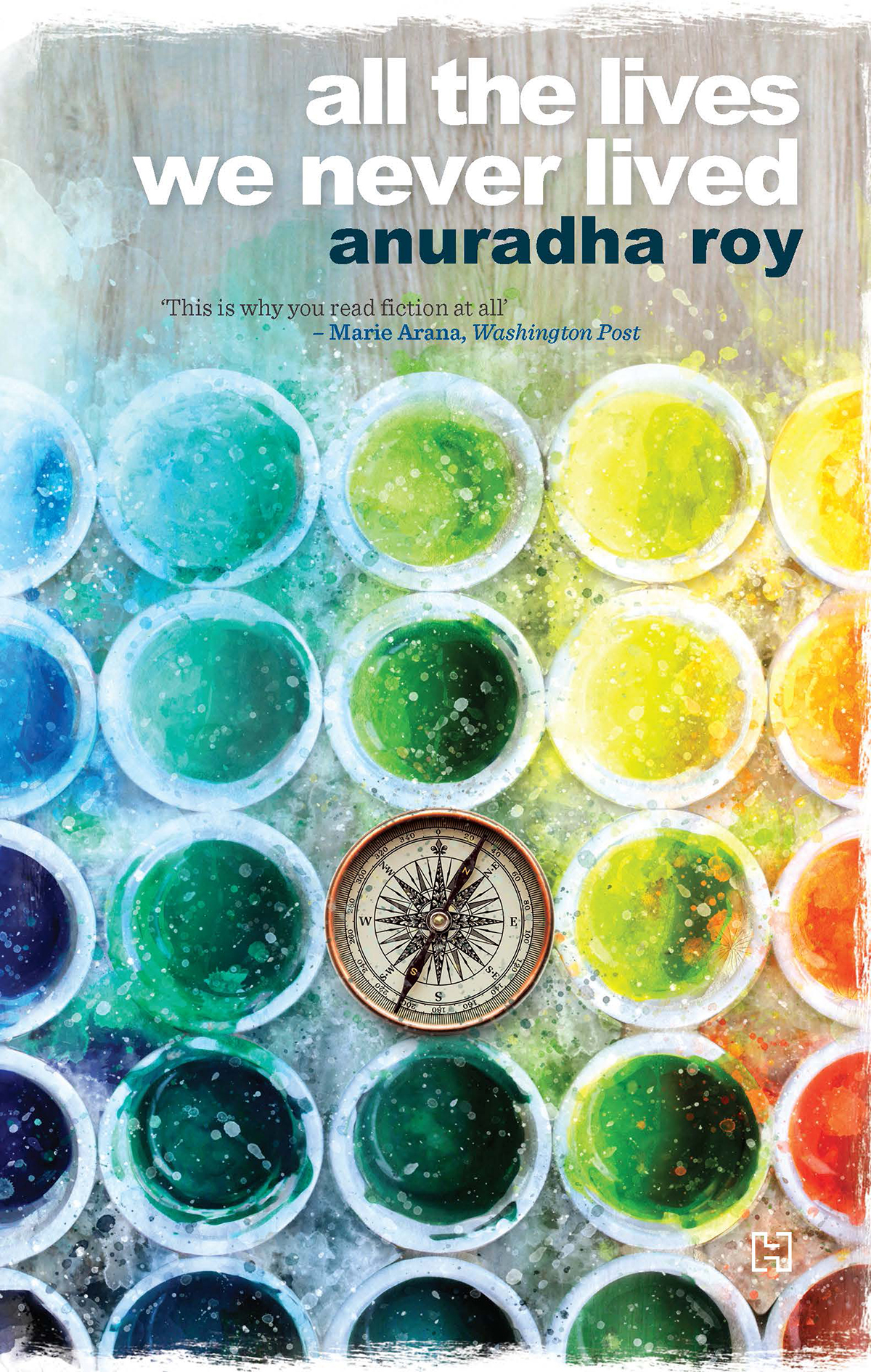

All The Lives We Never Lived, Anuradha Roy’s fourth novel, published by Hachette India, is the story of an elderly man, with the unusual name of Myshkin Rozario, looking back upon his life as he attempts to piece together the jigsaw of his mother’s abrupt disappearance when he was a child. The narrative is set amidst the turmoil of 1930s pre-independent India when freedom struggle is ratcheting up. Obviously, Gandhi lingers in the background, as do the Nazis and Hitler, while Rabindranath Tagore makes a cameo as Rabi Babu.

This novel has Roy’s trademark features that have won her previous books critical acclaim and commercial success: lyrical lucid prose, fully realized characters, a flawed female protagonist, sensuous evocation of a bygone era, a quiet examination of the myriad fissures of India. From its arresting opening — “In my childhood, I was known as the boy whose mother had run off with an Englishman. The man was in fact German, but in small-town India in those days, all white foreigners were largely thought of as British” — the narrative sweeps you along.

Gayatri Rozario, young, beautiful, gifted, troubled, is taken under the wing by the enigmatic Beryl de Zoete who is traveling the world writing on dance. Her companion, Walter Spies, is a German who has fled Germany, horrified by war and the Nazis, and turned to naturalism in the bounty of lush Bali. Why did his mother abandon her home and her child and flee to Dutch-ruled Bali with Beryl and Spies? This question drives Myshkin and the narrative, which is an extended meditation on the idea of freedom and how it can mean different things for different people: a nation, a woman, a non-native.

Nek Rozario, Myshkin’s father, occupied with the struggle for India’s freedom, cannot fathom why his wife would not model herself more on Mukti Devi, local leader of the movement. The mismatched couple are years apart, Gayatri having been married off at eighteen when her loving father died suddenly. His mother departs, his father is jailed, and Myshkin is brought up by Dada, his doctor grandfather in the company of Liza McNally, a family friend who feeds him cakes. Myshkin grows up to be a horticulturist, confounding the expectations of his father who believes a newly-independent India requires engineers, not gardeners.

Two-thirds in, the narrative becomes epistolary when Myshkin receives a bundle of letters written by his mother and we start to glean her reasons for leaving. At a languid pace, we learn of Gayatri’s life in Bali, her budding career as a painter, the buildup of tension due to war, the confinement of Walter Spies in British-allied and Dutch-ruled Bali, Gayatri’s attempts to stay afloat as the paradise around her collapses…

At its heart, All The Lives We Never Lived is an examination of the roles that define and constrain an individual, tempered as these roles are by the expectations of others. If Gayatri had never left, how different would Myshkin’s life be? If Gayatri was more the type of wife and woman Nek desired? If Nek was less of a political dabbler? If the war had not interceded?

Set in a small town called Muntazir, literally “to wait,” the novel evokes a bygone era, when a Mr Ishikawa, a Ms McNally, a Brijen Chacha were neighbors, not others, and India was cosmopolitan in spirit, the shrill demands of nationalism still at bay.

Excerpts from an interview:

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: Congratulations on your new novel! While it is set largely in pre-independent India, in its themes it seems very timely. Was the trigger for this novel the milestone 70th anniversary of independence or some other?

Anuradha Roy: This novel began innocuously enough for me — I wanted to write the story of a boy who lived such an intense life of the imagination that he inhabited the paintings he liked. I wasn’t thinking about the anniversary of India’s independence or any other themes at that stage.

The magical thing about the writing of it was how a whole world slowly started taking shape as I mulled over which pictures the boy would look at. At a museum in Bali, looking at the paintings of Walter Spies, I discovered he died on 19th January, the very day my beloved old dog had recently died. I know this sounds whimsical, but it felt as if my life, the novel and one real life character were connected. Slowly these ripples spread wider — as I discovered Tagore had met Spies; that Beryl de Zoete, who wrote a book with Spies, had come to India to write on dance. And as I found out more about these people who lived during a fraught historical period, it felt as if the two times, past and present, were like pictures on translucent wax paper, laid one on top of the other.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: Your novel is threaded through with the leitmotif of freedom and several of its offshoots — nationalism, cosmopolitanism, ghettoism, heroism, communalism. A character remarks: “Nothing works better in this country than ignorant religious faith …” Did you plan upon this resonance with our current time?

Anuradha Roy: Not to begin with, but yes — once the themes of the novel became clearer to me. It is a real struggle for me — for many of us — to grapple with the extreme changes in this country over the past few years. And placing myself in a past time when similar questions have played out — but very differently — was for me, a way of understanding my present.

I’ve noticed similar resonances in other novels set in the past — most recently, the way the world of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies often appears to reflect present-day compulsions behind global trade, religious tensions and wars despite being set during the reign of Henry VIII. When I read the work of Robert Seethaler, a brilliant German novelist whose books are set in wartime Austria, where the first signs of fascism are mere acts of vandalism, I am quite startled by the contemporary familiarity of it.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: If I am not mistaken, all your novels are set in small town India or a large part of the narrative is. Does the fact that you reside in Ranikhet play into the gentle rhythms of your storytelling, and if so, why?

Anuradha Roy: The attraction for smaller places probably has something to do with the fact that my growing up happened in small towns and remote hinterland areas all over India and these are still what I feel attracted to.

The second reason is that I make up my towns — and I choose the size of canvas I am comfortable filling up with events, people, stories. I don’t think of small towns as gentle or serene, far from it — though I know what you mean. Small places, the silence, their constrictions, the remoteness of them, somehow intensify the passions and dilemmas in the story.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: Was it always clear to you that you would tell the story via Myshkin? The device of looking back upon one’s life can create slackness in the story because there is little forward momentum in the present. However, to your credit, I was wholly taken in with Myshkin’s narrative. Could you share with us the choices you made while telling the story and why you chose to follow this particular one? Was your editor involved in this decision?

Anuradha Roy: No, my editor was not involved. He only read the first chunk of the book when I was about two hundred pages in. I decided to write it the way I did because I was writing a tragedy and in narrating it this way I simply followed one of the basic techniques of Greek tragedy, which is to tell you at the start what cataclysmic thing has happened and unravel the process that led up to it. It was a challenge to myself: was it possible for me to sacrifice “Suspense”, which is one of the main props of fiction? I was going to replace the “What next?” question with the subtler ones: “How did it happen? Why? What did it mean?” It leads to a more reflective novel, and may well be a risk. I am glad you think it works.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: Gayatri Rozario is an engaging addition to your roster of heroines — Nomi, Maya, Bakul — who have to navigate expectations and find their own path. With Gayatri, there is the added role of a mother, that too of a youngish child. The narrative examines how the demands of motherhood collide with a woman’s desire to fully explore her potential. The idea that a woman is not an end in herself is deeply ingrained in Indian society. Tell us how and why you decided upon this exploration?

Anuradha Roy: Gayatri came to me complete: a sparkling, gifted, sometimes abrasive, sometimes contradictory woman. Motherhood and nationhood are intertwined in our country, and Gayatri’s husband wants her to be both — the woman who will fight for her country on the street, and also stay home and look after her child. Her own needs and desires are dismissed by him as trivial. I wanted to explore the pain and exultation in the life of a woman for whom family and motherhood is not the end and start of everything — Gayatri has an inner core that is hers alone, it is a flame that lights her up and has nothing to do with her family, not even her child.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: Myshkin’s Dada, unimpressed with his son’s political activism calls his son, Nek Rozario, a “dabbler” in politics. But Nek serves jail term and has lofty ideas of how his countrymen and women should behave. I am curious what you think of Nek as a nationalist/patriot/Indian?

Anuradha Roy: I think of Nek as exasperating, but a man of integrity and courage, and there is one moment in the book when Myshkin, who has been at odds with his father all along, realizes what he means to the wider world. The nationalism Nek and his leader espouse, the Gandhian kind of nationalism, was dictatorial in many of its aspects, but it was inclusive and idealistic, nothing like the jingoism that is passed off for patriotism today. Nek is dogmatic about his views however, and often dim — especially in his inability to translate his generalized compassion for all humanity into empathy for those close to him.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: The novel is strewn with so many beautiful friendships: Dada and Liza McNally, Gayatri and Walter Spies, Beryl and Walter. There is an ease in these friendships across nationalities and genders which makes for a cosmopolitanism which seems to be missing in today’s India. Comment?

Anuradha Roy: It is missing, isn’t it, more and more. One of the things that struck me powerfully when working on this book, and reading the travelogue in Bengali about Bali by Suniti Kumar Chatterji, was the cosmopolitanism and curiosity. These were travellers in 1927, and yet the conversations they strike up in faltering Dutch and Malay and French are so astonishing — even just the effort of it. In one section of Tagore’s letters from Java, he talks about finding himself on a longish car journey with the Raja of Karangasem, a province in Bali. They have no language in common and go through the ride in silence until at one point the Raja glimpses the ocean and points to it, saying to Tagore: “Samudra”. Then, reports Tagore, the Raja began to rattle off all the synonyms for ocean in Balinese, and once he had exhausted those, he started on the names of Hindu deities — rapturous that the words and names had the same Sanskrit root. The need for communication, across cultures despite the lack of language was very strong. Tagore was a great example of this, travelling tirelessly, despite age and ill health, forming new friendships in very old age, thinking of Santiniketan as a “nest for the world”. Now, there is a parochial closing of doors.

A common thread in my books is unlikely friendships: in the first book there was Kananbala, an old Bengali woman who strikes up a wordless friendship with an Anglo Indian across the road; in Folded Earth, Maya’s friendship with an elderly eccentric, a man who was once a Diwan, is her closest. There is something about these friendships that I find complex and interesting to explore, much more than I do conventional romances.

Anuradha Roy. Photo: Guillaume Bonnier

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: When Gayatri flees, it is assumed that she has run away with the white man. Yet, Walter Spies is gay. I love the way you cock a snook at our cultural assumptions about the only kind of relationship that can exist between a man and a woman. While the Gayatri-Walter relationship is free of sexual tension, Walter is imprisoned later because of his homosexuality. Can you talk a bit about how you interweave the notion of freedom and freedoms throughout the story?

Anuradha Roy: When a woman does something — especially leaving home with an alien man — it is usually assumed she is doing so only because she is besotted by that man. And Walter Spies was a very charismatic, handsome man — as described in the book. I liked the piquancy of a young woman running off with a gay man who is taken to be her lover. What the two of them actually share is not sexual love, but the need for freedom to live as they please, and to be true to their gifts. In many ways Spies really symbolizes the cosmopolitanism you asked about earlier — and in Bali he built up a community of artistic people that had no borders or nationalities at all.

Nek’s leader in the political battle, a frail, steely old woman called Mukti Devi, is another woman who, like Gayatri, has chosen her own path. In her case, it is to fight for the country’s freedom. It is just that each version of freedom is different.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: Myshkin’s relationship with the flora under his care is rendered so very tenderly. The building of a flyover “sentenced to death 44 neem trees…”. Additionally, his easy camaraderie and comfort with his dogs. I know that you have dogs of your own, and I believe a dog or two features in each of your novels. What is the wellspring of this love? (Disclaimer: I am a small-town girl who believes canine love is often superior to that of humans.)

Anuradha Roy: Last year, I was at a huge exhibition in Paris which brought together much of Gauguin’s works, and I was struck, as I looked at the paintings, sculpture, wood carvings, and ceramic works, how many dogs there were in his paintings — not as the central subjects but a part of the scene, just lounging about, or playing. In one of Spies’ huge paintings depicting Balinese life, you see a curly tailed dog in one corner. I suppose your own affinities do enter your work, and I know loving dogs and having them from my childhood in real life means there are quite a number of them scattered through my books. People keep asking in what way my novels are autobiographical: this is how!

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: Through Gayatri and Brijen, characters who like to paint, dance, write and sing, the narrative limns what the pursuit of art entails. Do you feel a kindredness of spirit with these characters whose lives as artists are sorely misunderstood by their families and the world at large?

Anuradha Roy: I am fortunate in never having faced a hostile environment at home for my work but the characters in the book are not so lucky. Consequently, they have to find friendship and understanding in each other. In the book, Gayatri’s encounter with Begum Akhtar is a life-changing one for her, as are her relationships with other writers and artists, including Spies and Tagore, in environments where she otherwise feels isolated.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: An adult Myshkin seems a composite of his very different parents. Like his father, he resides in the outhouse where he writes. And in the manner of his mother, he makes detailed sketches. Was this deliberate or did Myshkin shape out in this fashion as the

narrative grew?

Anuradha Roy: That is a perceptive point about him — but it was nothing I contrived. Myshkin took shape very naturally as I wrote. What he evolves into as an adult comes from his childhood.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: Two-thirds into the story, the narrative becomes epistolary with letters from Gayatri Rozario written to Liza McNally. This is a distinct shift in tone, POV, pacing. What made you decide on this switch? Did you consider other ways of taking us into Gayatri’s narrative?

Anuradha Roy: What I wanted was Gayatri’s experience of Bali and her new life, in her own words. I could have written that in straight first person of course, but I wanted to take the theme of friendship further with these letters, needed the intimacy of tone there is when writing to a close friend, and the immediacy of someone writing in her present. The letters also allow me to evoke a sense of her isolation and uncertainty. There is the waiting for letters, the ones that go missing — so much a part of life in the age when the main way of communicating was through letters. In the memoirs and books I read on the war, a striking and moving aspect was how, everywhere, people waited in the same way for news from the post, the telegrams. There used to exist a whole culture of writing letters, the slow thinking process that went into writing them, the calligraphic aspect showing you something about the letter-writer, the flow of ink, the little things you enclosed with letters, the long wait, the excitement of slitting open an envelope: this whole experience has been lost because of the need for instantaneous interactions.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: I love how the multiculturalism of India lurks throughout the narrative, be it the Anglo-Indian Rozarios, the town’s Urdu name, the dentist Ishikawa, marsiya singing … Is there a nostalgia for bygone times?

Anuradha Roy: It is true that that variety of multiculturalism is gone now, and this is a huge loss — these small towns seem duller, cruder, somewhat monochromatic. But no, I don’t feel nostalgic for the past, there were different problems then. Nostalgia is a romantic yearning for the past and the perpetual, deluded sense that things were better “back then”. If anything, this novel shows that things were not remotely better before: the patterns of oppression, violence, meaningless death, parochialism that we see now existed just as strongly earlier.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: The Bali scenes illustrate the cultural linkages between Indonesia and India, the ways in which we can be tied to others who might appear distant and/or unfamiliar. At the same time, you contrast the manner in which women conduct themselves so differently in the two places. Why did you feel the need to recount this?

Anuradha Roy: I was very struck by the way my response to Balinese women (during my trips there) was echoed more or less exactly by Suniti Kumar Chatterji in his travelogue about Bali written way back in the late 1920s. He kept pointing out the ways in which Bali and India were culturally and religiously close, but he recognized even then, the barbarism of the way in which women in India are suppressed.

Despite sharing the same religion, this was not the case with Balinese women then — or now. Since Gayatri is an Indian woman in Bali, it is natural for her to notice the women around her, how their freedom and physical ease contrasts with what she experienced in India.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: Urdu and Bhasa script are used beneath chapter headings. Was this to signify Muntazir and Bali as settings or is there a more particular reason for that?

Anuradha Roy: These are both beautiful scripts and using them served the practical purpose of both telling us where we are (since the book is set in two places) as well as decorating the opening pages.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: Finally, a few questions on the writing of this book. How long did you take to write it? Was your research a concentrated effort or accumulated over time?

Anuradha Roy: Primarily to get a sense of the landscape and atmosphere, I travelled to places in Bali which had special meaning for Walter Spies. It was fascinating to see how the landscape and colours of Bali are transformed into magical, mesmeric images in his paintings. Other than the travel, the rest of the research was the usual mix of reading books and old newspapers, and asking people questions. I do not follow all the facts. Characters from history are fictionalized here, including Rabindranath, even though I read a great deal about his actual travels in Java and Bali in order to create his fictional journey.

Every novel has to be researched, and so did this one — but I am not interested in making a fetish out of it. Despite all the ideas and history in the novel, the main thing for me is to create an emotional charge. Primarily, I don’t need people to learn from my novel.

I want them to feel and think and be immersed in its world. If they do get sucked into the life of the book, its intellectual and moral directions may (or may not) influence them.

How long did it take to write: about three years.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: Considering this is your fourth novel in a span of ten years, my next question might be the wrong one to ask but do you face writer’s block? If yes, what’s your mantra to unblock?

Anuradha Roy: If I can’t write, I just do something else. It’s a waste of time to struggle and stare at blank pages or screens. I think of the fallow periods as a time when things must be — well, I hope they are — happening inside your brain… in the way you sometimes wake up from sleep with a solution to a problem. If I am stuck with particular sections of the novel, then I go for a walk and it usually sorts itself out.

Manreet Sodhi Someshwar: Who or what are your inspirations — for your craft and your life?

Anuradha Roy: Through the writing of this particular book, it was certainly Walter Spies. His entire brief, dazzling life is an inspiration. I often think of the way he created great paintings and composed music and found happiness — even in dingy prison cells. This is not a gift given to many.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated