Arun Maira, former member of India’s Planning Commission, who worked as a member of the Tata Administrative Services for 25 years, credits values, standards and people-centric operations for the enviable organisation Tata has come to be, in his book, The Learning Factory. Photo: Penguin Random House

“The Tata Group is more than just a company. TAS is more than just a career. If you’re seeking the career journey of a lifetime that is enriching, fulfilling and challenging, this is where you start.” Even in this age of job-hopping, this recruitment banner of the Tata Administrative Services still holds true in 2020. The sheen that brand Tata enjoyed amongst Indians, and internationally, may not quite be at its peak, but the journey of the Tatas — one that has run parallel for the most part to one of modern India — embodies perhaps some of the values that India’s Constitution writers dreamt of for an independent nation.

Take note of the latest ‘controversy’ — the Tanishq Ekatvam ad that was unbelievably panned for projecting a composite vision of India – depicting a marriage that crossed the divides of religion. This is not the first time either. Their idea of diverse Indian strands getting woven together in a modern India was most notably critiqued when a Tata Steel ad in the late 1980ssaid “ispat bhi hum banate hain (we also make steel)”. The emphasis was that it also did many other things. The complaint then was that it was too ‘socialist’.

The Tata group, in its more-than-a-century-old journey, has often been acknowledged as ‘nation builders’, standing for certain values. Arun Maira, who needs little introduction to India’s governing class, having served in multiple leadership positions in the private and public sector, including as a member of India’s Planning Commission, and as a member of the Tata Administrative Services (TAS) for 25 years — his longest work stint. In his new book, The Learning Factory, he credits values, standards and people-centric operations for the enviable organisation it has come to be while narrating stories — about people, places, and unique challenges as well as how the organisation responded to them.

This is not a history of the Tatas though, but could be seen as case studies about a company that put people at the core of the company. Many interesting anecdotes—why Jamshedpur’s example as a steel city was not followed in Pune; how when MBAs began to get higher salaries, there was an internal debate; how strikes were resolved; how leaders of foreign countries would make a beeline for the ‘Taj of Modern India’, and, above all, how just the Tata name opened doors —are strewn across its pages. Excerpts from an interview:

Your earlier books, such as Remaking India: One Country, One Destiny (2004) and Discordant Democrats (2007) were books that addressed socio-economic issues at a wider scale. What led to this book, which is essentially a number of stories and anecdotes from your time at the Tatas?

This book came about in a flight from Delhi to Singapore, when I was sitting with my friend Tarun Das, long-time mentor of The Confederation of Indian Industry (CII). He started to reflect with me about Singapore, how it had grown so remarkably well, and as a contrast, India not so much. I mentioned that at one time, I used to go frequently as Lee Kuan Yew had requested JRD Tata for help to create a skilled workforce and to kickstart the industrialisation of Singapore. It is interesting that Singapore, the city-state we admire today, learnt from the Tatas. In India, we have been struggling with the skilling of the workforce, which has not been happening enough and industry has not been growing.

Were the Tatas becoming ‘a learning factory’, especially post India’s independence when national self-reliance was a compulsion, and do the Tatas still play this role?

Of course, at all times, you may not have what you need at that time, and that is the point of creative entrepreneurial ventures. That’s always a challenge. You might have to create what you need while you are changing into the new. Certainly, India has changed from the time I am writing about. With the liberalisation of the global economy, the idea that we need people to trade with each other, and good things will begin to happen by themselves as it were, leaving it to the market and somehow the whole gets improved, this idea is prevalent — in management, economics and public policy for the last 30-40 years. Certainly India has changed from the time I am writing about, and certainly the Tatas have had to change to go with this. So, even Tatas have to go along with the paradigm of globalisation that became prevalent — you have to be a part of the general policy that goes for everybody.

When I came back from my nearly ten-year stint in the US, I noticed the struggle Indian business people, Tatas in particular, were having. There are people we call business people — such as the Tatas — and then you have people who are big traders, who are business people,too. I began to see that the voices of people who are not really builders of industry, but are growing large enterprises, basically with trading, are becoming very loud in policy-making. They support the notion of free trade as it enables them to bring in what they want to and sell here. What is valued now is the size of the enterprise in financial terms — and we celebrate those. If you have a $1 trillion market valuation, it is seen as a good thing. Whereas if you take pride in making something in India which Indians couldn’t do before, you are seen as being self-reliant, and questioned on what that does for the country and for business. This is the struggle the Tatas have also been having, to my knowledge, for the last few years. As you play by general rules and not by your principles, you get transformed. Tatas aren’t exactly the same as they were then. That is what Tarun said — don’t write economic theories, just write the stories and let people derive from them.

The Learning Factory: How the Leaders of Tata Became Nation Builders,

By Arun Maira, Penguin Viking

Pp: xix+249, Rs 499

The Tatas, in Indian perception, and possibly fact, are different from other corporations in India. However, especially among young Indians seeking to get into business or management, Tatas would not be the first choice for many. This book details so many wonderful stories about what the Tatas did to shape India’s growth, but right now they are not capturing the imagination. Do you see a reason for this? In what ways would you say the Tatas differ from other corporations, especially in the way they internally operate?

In the times I write about, we were talking about building industrial enterprises as India needed them. We are talking about people with engineering backgrounds. We didn’t have MBAs then, though the IITs of India were world-celebrated. Nowadays, we are saying India needs world-class higher education institutions — we had done it before.

With the advent of the software firms in the late 1990s, who offered jobs abroad and on computers, young engineers began to gravitate to IT companies. IT has done many good things for the country, including allowing young people to work and travel abroad, which is very attractive for a young person. Young Indians began preferring the IT industry, and this sucked out the resources industry and manufacturing needed. TELCO (now Tata Motors), Tata Steel, Tata Chemicals — the foundational industries that the Tatas built — were no longer as attractive, even to engineers. Young people were coming to management courses from the IITs — with probably the best engineering education in the world —and landing up in consulting companies, where they were now trying to advise the hardcore manufacturing managers how to run their enterprise. So, there was no development experience, which is what I bring out in my book — Sumant Moolgaokar telling me that you learn on the shop floor, learn from the people. It’s not just about numbers and equations. These forces began to change the availability of resources for manufacturing in India. We couldn’t get MBAs or engineers. While we still had skilled workers, if the managers of the skilled workers have no respect for them, the structure of the enterprise begins to become rather shaky. Now, managers have a management school background, so when they come looking after workers, they go along with the thesis that you must allow managers to have flexibility to hire and fire and the freedom to reduce the cost of the input, which they call labour. In my times, workers were the essence of the organisation. They built it, and you had to build them and yourself together and thus you had a learning enterprise.

Would you say the people who were part of the Tatas when you were there — given the distinct way the company functioned, embodied different values or led lives differently, even after they retired or were not part of the company?

I absolutely do. I find that for these people — now mostly in their 60s or 70s —grew up 30 or 40 years ago and that is when their values and what they treasured about living were shaped. For example, I find these people would not show off money as much as people in the financial sector in India. One can see this around — people in the financial sector are making money out of money, so they get richer faster. You can see the holidays they take etc. I noticed the ‘Page 3’ phenomenon when I came back to India. Even the business magazines — earlier they were celebrating enterprises and ideas, not individuals so much. Now, you have to have some ‘big chap’ on the cover with his arms folded, and it says ‘wealth creator’! There has been a shift towards people and their egos and putting them in the front. I find that it is not what the older Tata people value.

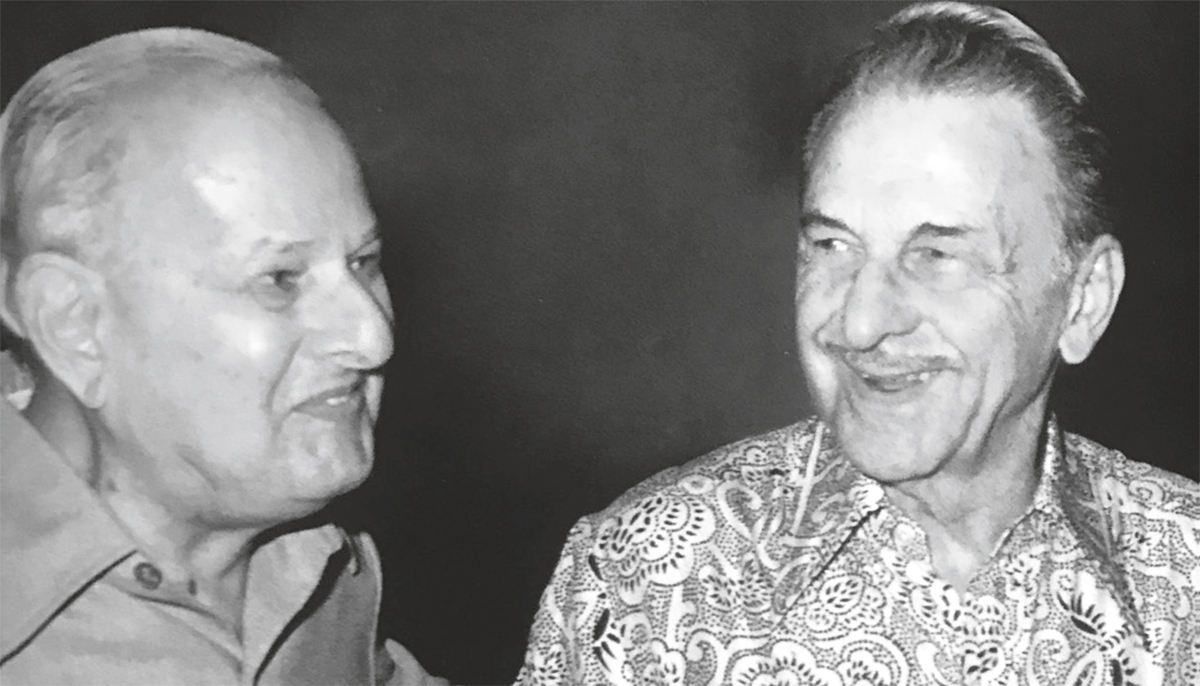

Sumant Moolgaokar and JRD Tata, two good friends and partners in building industrial India. Photo: Penguin

How do you think these values of self-fulfilment rather than nation-building (which the Tatas were known for) will impact as people become centred around their own concerns?

Right. Manmohan Singh is celebrated as the liberator of India, and many say that life started in India after 1991. I remember the CII invited Dr Singh for their AGM, the big function they have, in 2006, I think. He told the audience that since they had invited him as an elder to give advice, he was going to take this seriously. He said he would request the audience to pay attention to ten things. One of those things was:“Please don’t show off your wealth so much.It’s obnoxious and obscene in a country where there are so many poor people. You have achieved your success but they haven’t yet.” He also said,“Please respect those who work: your wealth is taken off their backs.” He mentioned the problems of health and education in public services and the need to support them. He laid these things out.

After his address, I got calls from journalists. They asked if India was going back to the socialist era. However, Dr Singh had said that we must continue to expand our economy, open up our systems and institutions, but also take care of the poorest people in the country. That was his message.

Later, when Dr Singh hired me for the Planning Commission, I told him that I was not an economist and wondered whether he was sure he wanted to hire me. He smiled and said, “Of course, I have known your history, Arun. You were with the Tatas. That’s why we want you. We want to look at industry very differently. We are growing our economy but our manufacturing is still so small. We need people who know how to build an industry in our policy circle. It won’t be easy for you, but we need the views of outsiders. He also said that ever since he gave that speech, they didn’t want him to come to their meetings.

The Tata Steel ad, where they said ‘We also make steel’ was withdrawn as they were being misread as they were responsible for India and society and not just profits. People thought the whole point of an enterprise was to make profits.

With Sumant Moolgaokar in Tokyo around 1985, at dinner hosted by Board of Honda Motor Co on signing of collaboration agreement with Telco. Photo: Penguin

Of the many stories you narrate in the book, are there any that stand out in particular from your time at the Tatas?

They are all special, particularly my conversations with Nani Palkhivala — because it is so relevant to what we are saying — about who gets precedence in the good times of companies and who has to take the rap during bad times. The equation between the markets and shareholders and workers. I was reading that whereas in the 1970s in the US, people held on to stock for about four years, by the end of the last millennium, they were holding on it for some weeks, and last year when they measured, it was a few seconds only. Shareholders don’t even know this. All this trading via technology, stock market fellows are just looking at blips up and down, and doing it even faster. How are they owners and vested at all in the life of the enterprise?

The feeling about these stories is that we are short-changing Indian people and workers. During the lockdown after Covid-19 outbreak, all the workers who spilled out on to the roads, who were they? They were working somewhere, in some form of enterprise. There was no concern about the condition in which they were nor about the security of their employment.

The Tatas have had exceptional heads of organisation. How much of a difference did that make in the way the group functioned?

That has to be so, because it is about yourself, what you value. If you, in your own organisation, create norms that you will admire those who are earning more rather than those who are contributing by their hard work and ideas, you will change the values. During my time, I was in-charge of recruitment, and we were initially getting MBA toppers from Ahmedabad and Calcutta, the two that were there, especially for our TELCO management programme, where you got a slightly higher salary than a graduate engineer, because you had put in a little more time in education. But there was also the message that you actually know less as the others have put in more work. The camaraderie was there. When the MBAs started getting attracted by Citibank, Levers or ICI etc, they were being offered higher salaries as they were now ready-made managers to those companies. We found that if we were to continue to offer jobs to people in these institutions, we would have to raise our salaries, which would disrupt our internal feeling of being one organisation. So, we stopped. I remember that one year, we said we were not coming to these two institutes. There was a shock in these institutes as the best people wanted to come. The placement officer of IIM Ahmedabad came down with the dean, and we had a very good discussion about these matters. In those early days, these institutions wanted to show that if you join their institute as a student, you are likely to earn a higher salary. It’s a metric of how good the institution is. Today, all management are rated by salaries that are offered to their students, often by financial firms, consulting firms and so forth. They are now catering to the needs of those firms. Their curricula are no longer directed towards real learners and patient builders of institutions.

JRD played a seminal role in the spread and growth of the Tatas. It was also a time India was setting up new industries. He would find somebody who had fire in the belly and the right values. He kept a good eye on the human values. Fairness to your employees, fairness to your stakeholders — that’s JRD’s big stamp. He also credited people like Sumant Moolgaokar, about whom he said that after Jamsetji Tata, the person who had a vision for an industrialised India was Moolgaokar, not himself. Moolgaokar is not even remembered by the people. JRD and Ratan led in different times. Ratan Tata and I were the same grade, he and I often travelled together when JRD suggested that the Tatas should look for new opportunities in the agricultural sector. He is a lovely person, and has an air of simplicity about him. People who have worked for him such as B. Muthuraman (of Tata Steel) revere him.

What could younger executives or management students imbibe from this book?

Management schools today teach ethics, teaching potential leaders to respect all stakeholders. How do you do this? Ethics is about your dilemmas. If people are pushed more towards the financial results because that is noted and celebrated, and your salaries get linked to financial results, then in the immediate complicated decisions that they take, they are going to be inclined to favour that. You have to show people business managers how to take that decision when they are in situations where financial interests as well other interests, e.g. workers interests, are involved. It’s a case study. It’s not easy. These are the stories I bring out. The Tatas are financially successful, too, or they wouldn’t be so big, but they have continued to have other values also.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated