There are cities in which we are born, cities we grow up in, cities we study in, work in, migrate to, travel in, so that our bodies start to become — gradually — a home to all the cities we inhabit.

The works of two Indian poets, Tishani Doshi and Arundhathi Subramaniam, are concerned, in some ways, with the navigation of space(s) and the forging of identity in its context; there is a reflection on personal experiences as well as a contemplation of the world

“Cities, like dreams, are made of desires and fears, even if the thread of their discourse is secret, their rules are absurd, their perspectives deceitful, and everything conceals something else,” notes Italo Calvino in his famous book ‘Invisible Cities’ (1972). Elsewhere, in the same book, he writes how travelling to a new city can lead to finding/remembering a part of our past that we weren’t aware existed because “the foreignness of what you no longer are or no longer possess lies in wait for you in foreign, unpossessed places.”

There are cities in which we are born, cities we grow up in, cities we study in, work in, migrate to, travel in, so that our bodies start to become — gradually — a home to all the cities we inhabit. In an attempt to study how cities are presented in poetry in different colours, I’ve chosen to closely look at the works by two of my favourite modern poets, Tishani Doshi and Arundhathi Subramaniam. The works of both these poets are concerned — in some ways — with the navigation of space(s) and the forging of identity in its context. There is a reflection on personal experiences as well as a contemplation of the world.

Cities as Spaces of Threat

Constructed and governed primarily by men, cities often pose numerous threats for women — whether it is in accessing the public space through transportation, visiting historical sites, shopping, etc., or to make a private space of one’s own in the form of individually homed houses. They are rarely as welcoming to people who do not identify as men. Newspapers are forever flooded with tragic happenings to women and queer-folk and so they are left to devise their own ways in order to navigate through the dark alleys of a city even during day.

In ‘Walking Around’, Doshi responds to the Chilean poet, Pablo Neruda’s poem of the same name. She notes: “All along the streets there are forlorn mansions/ where girls have grown up and vanished. / I am vanishing too.” Where Neruda’s narrative is concerned with the futility of life, it is essentially a personal one, in which the poet strolls along the streets of his city and continuously states how tired he is of being a man. However, just when he is at the crux of this utter hopelessness, he finds himself excited at the thought of killing a nun “with a blow on the ear”. Disturbing as it is, violence becomes in the poem, at this point, an act that causes the poet to reconsider his oth0erwise bleak perspective on life.

Though Doshi’s poem is concerned primarily with the narrator’s feelings — her done-ness with her body, her resistance to an ascribed woman-ness — it also mourns the disappearing of daughters for whom the walls weep. The beginning of this poem — “It happens that I am tired of being a woman” — stated as a fact that long awaited its utterance, is at once reminiscent of the powerful verse of Anne Sexton’s ‘Consorting With Angels’, which begins in the past tense: “I was tired of being a woman”; goes on to express the poet’s exhaustion about the “gender of things”.

On coming across such raging and biting declaration, one wonders at the universality of suffering, and the sharing of similar sentiment across oceans. It is not to limit the woman’s experience to similar violence(s) but to rather identify how, and more importantly why, she is always at the receiving end.

In another poem, ‘This Could Be Enough’, Subramaniam’s voice sounds relaxed, like she’s loosening up after a good drink. “…this evening/ of muddled longing and rage” on which Subramaniam contemplates over the sufficiency of sisterhood is intervened by the lustful (and violent) gaze of men.

Yet, the togetherness she shares with women around her defeats “the man at the far table/ glowering with lust”.

Cities as Spaces of Identity Formation

Cities that are personal to these poets — interestingly, Madras figures as a common city that they have regularly returned to in their poems — sometimes appear in intimate, tender, and evocative moments. An almost fleeting image that transcends space and time, accessed through memory.

“Sometimes in the desert

the wind will blow through my shell-shaped ears

and whisper a sea song just to taunt me”

(writes Doshi in ‘Listening to Abida Parveen on Loop, I Understand Why I Miss Home and Why It Must Be So.’)

Elsewhere, Subramaniam reminisces on how cities annex you, through memories:

“and the taste of coffee one day in Lucca

suddenly awakening an old prescription – ”

(from ‘Madras’ that first appeared in the poet’s collection entitled ‘Where I Live’)

Past often has a way of holding us hostage in the present and in return it asks — sometimes — for attention. It urges and divulges us from the present to the land of memory, oscillating perpetually between the acts of remembering and forgetting.

The city of Madras, in a similar way, is drawn in words and experiences of the poets elicited in redolent ways. In ‘Madras, November, 1995,’ for instance, Subramaniam emphatically sings:

“No, I am not sentimental

about the erasure of dynastic memories,

the collapse of ancestral houses,

but it will be difficult to forget

palm leaves in the winter storm…”

Elsewhere, Doshi notes:

“We are homesick everywhere

even when we’re home we are empty things

that need filling

we are always lost in love never found

please come find me”

In the vulnerability of these lines is an existential question of belonging — who belongs where, and when? Belonging becomes gendered. And we hear Doshi offering a small solution, as a way to become happy in 101 days: “Renounce your house.”

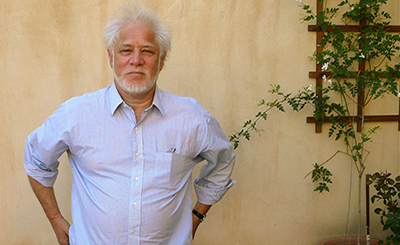

Tishani Doshi (left) and Arundhathi Subramaniam.

Where cities lead to such piercing questions and bold answers, it also becomes a refuge in delicate ways, to ascertain for example, a kind of sisterhood.

In ‘Meeting Elizabeth Bishop in Madras’, Doshi meets the poet at a dentist’s clinic in Madras: “Yet here you are. Isn’t this togetherness?”

Amusingly, Doshi describes the physical surroundings to Bishop as if she were having a live telephonic conversation with her, reporting, detailing, sharing personal opinions — often witty and humorous. In the pure physical absence of Bishop, Doshi seeks answers to questions that are intimate, political and at the same time philosophical. Questions that can only be asked to someone if one relates to their experiences, writings.

“- will someone console me?...

And what can be said about darkness after all?

About men who board buses with iron rods?”

In her own way in ‘5:46, Andheri Local’, Subramaniam becomes one with the Bombay local train: “A thousand-limbed/ million-tongued, multi spoused/ Kali on wheels.” The poet’s self merges with all the others surrounding her, inhabiting the same space as her, so that now they constitute a singular body.

Interpretative of a shared collective consciousness, the poem’s invocation of the image of a “Kali on wheels” is at once modern(-ist) and lends a witty charm to the verse — characteristic of Subramaniam’s poems.

A journey through words

“Alone, I crossed the Field of Emptiness,

dropping my reason and my senses.

I stumbled on my own secret there

and flowered, a lotus rising from a marsh.”

— Lal Ded 110, translated by Ranjit Hoskote

When Lal Ded exclaimed so in the fourteenth century, little would she have known that her “own secret” — this becoming a rising lotus — would become a framework for understanding the marsh. This rising may remind one of Sylvia Plath’s ‘Lady Lazarus’, and it could perhaps be said that the unique-ness of poetry written by women, the subjectivity that they present has long been due for its lotus-like rising. It is important however, to resist bracketing.

In an essay on contemporary Indian poetry, published in Sahitya Akademi’s ‘Indian Literature’, Subramaniam eloquently points out the limits of perception and criticism. She writes how comparisons often lead to a ‘hashtag’ approach, reducing poetry to a set of terms that not only belittles but ignores the poems’ depth and “variety of the scene”. Attentive reading, focused examination and responsive listening, Subramaniam suggests, are the only way to curb the hashtag approach.

In a similar way, works by writers who identify as women have suffered a unidimensional understanding that restricts them to certain keywords — question of identity, body, personal “I”. And though this essay is an attempt to examine some of the texts that belong to this category, it is also an attempt to dispute that kind of criticism.

For the modern poet, cities have proved to be points of intense philosophical contemplation. Calvino’s deceitful city is often a space of comfort, remembrance of past, a source of contentment, and sometimes frustratingly corrupt. In Doshi and Subramaniam’s poems, one finds all these elements. Where cities are remembered through objective facts (historical, geographical, political), they are also relived through subjective understanding — offering the reader a journey through words, where spaces are constantly created, painted, mourned, and celebrated.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated