Devashish Makhija. Photo courtesy of the author

The author, filmmaker and screenwriter on his first novel, Oonga, set against the backdrop of the conflict between the Adivasis, the Naxalites and the combined might of a rapacious mining company and the CRPF, controlled and directed by the State

Devashish Makhija is a storyteller and a powerful voice of resistance who wears many hats. He is a filmmaker and screenwriter, having written and directed critically acclaimed short films, such as Rahim Murge Pe Mat Ro (2008), El’ayichi (2015) and Tandav (2016) as well as the riveting feature films, Ajji (2017) and then Bhonsle (2018), embodied by the exceptional Manoj Bajpai.

He is also a best-selling author of children’s books, with When Ali Became Bajrangbali (2012) currently in its eighth reprint and the whimsical Why Paploo Was Perplexed (2011), a delightful tale that explores our world through a child’s imagination.

His anthology of short stories, Forgetting (2014), establishes his mastery as a fiction writer and Occupying Silence (2008), a collection of graphic verse is an expression of his sensibility as a graphic artist and poet.

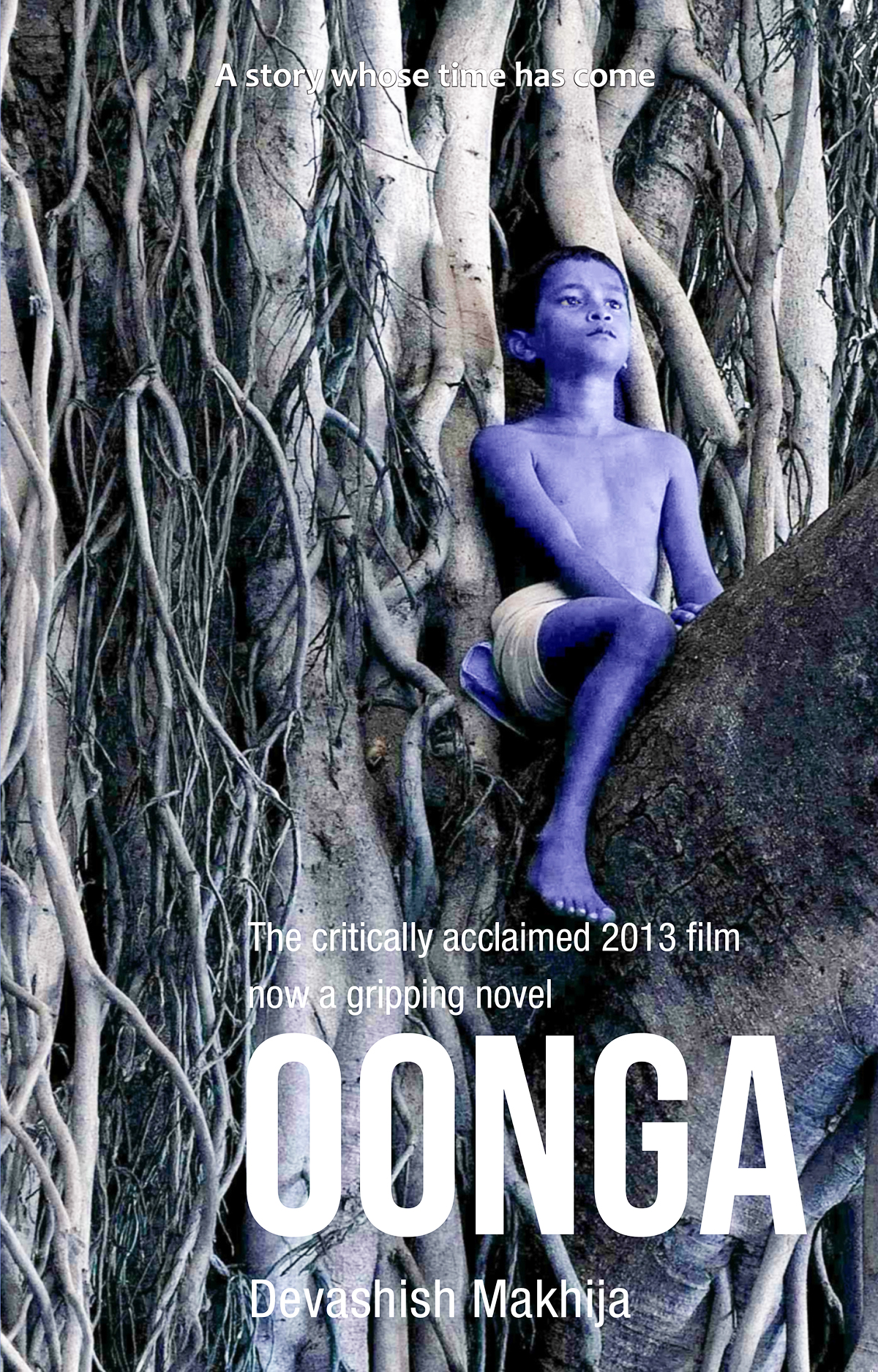

Oonga, published by Tulika Books, is his first novel, set against the backdrop of the conflict between the Adivasis, the Naxalites and the combined might of a rapacious mining company and the CRPF, controlled and directed by the State.

Fresh off the launch of Oonga at the Jaipur Literature Festival, the author talks about the journey and the questions within that led to the birth of this extraordinary tale.

Excerpts from an interview:

Nandini Sen Mehra: First of beginnings. The unusual journey of Oonga, the book, seems to draw parallels with the adventures of its plucky young protagonist. Take us through how it came to be?

Devashish Makhija: The story of Oonga finds its seed in a small anecdote I heard while in Koraput, Orissa over ten years ago. Sharanya Nayak, then the local head of Action Aid there told me how she had taken a group of Adivasis to watch a dubbed version of Avatar. They hollered and cheered the Na’vi right through the film as if they were their own fellow-tribals fighting the same battles they were. They felt like it was their own story being shown on that screen. But they were shocked when the film ended. It ended ‘happily’! That group of Adivasis had been fighting the same battles the Na’vi were, for years, and losing. The film suddenly seemed to betray them and their own realities. I thought this needed remedy in a story that would attempt to be more authentic to the Adivasis’ heartache with the State and Industry. This intent brought me to Oonga.

Nandini Sen Mehra: How did you come to meet Oonga and was there a specific point in time when you realised, this was a story you were going to tell?

Devashish Makhija: I’ve been perplexed by our education system all the way back since Class 5, when even while studying history we were made to accept rather simplistic ‘truths’ about our leaders and our past. I always doubted what our elders and teachers insisted was the ‘truth’. As the years passed, I started to understand that this ‘truth’ is so complex that it cannot be processed by a juvenile mind. Hence, our earlier years become an endless series of learning, then unlearning, then learning the same thing again with fewer presumptions, and then unlearning it yet again when new complexities present themselves. Some of these questions found their way into two very Oonga-like children’s books —Why Paploo Was Perplexed and When Ali Became Bajrangbali — the first questions the things we make little kids presume, while the second does what Oonga does, questions the ‘gray areas’ of development, and even religion, while we’re at it. Both of these have been published by Tulika in the past. Neither of us imagined we would arrive at a novel together some day. (Note here: This is Tulika Publishers’ first-ever full-fledged novel).

In all my stories (films and books), I do strive to keep trying to hold up that mirror to ourselves. I think we as a species, a nation, a people, don’t look into our souls often enough. We humans pride ourselves in our ‘consciousness’, our emotional superiority over other creatures. But most of the time we leave it at that, revelling in the vanity of this superiority, never pausing to look at ourselves for what we really are — the greediest, most destructive, short-sighted species on earth. I suspect we’re shit scared of our own selves. It’s not just our political decisions that I’d like us to reconsider, but our social, economic, industrial, consumeristic, environmental, emotional and philosophical ones as well. And if I can, I’d like to catch my readers young, when their minds aren’t tainted by the societal-conditioning and cynicism that living in cities for many years brings.

Oonga is perhaps an attempt to achieve all of the above.

Nandini Sen Mehra: When I read the book it seemed as if Oonga’s perspective as a child navigating unfamiliar terrain, both in a physical sense as well as the often incomprehensible world of adults, echoes the bafflement and challenges that perhaps self-contained indigenous people of the land may feel when they encounter urban motivations and drivers, so alien to their own. I’m curious about your reasons for telling the story largely through the eyes of a child.

Devashish Makhija: Little Oonga is an embodiment of the Adivasi’s naiveté towards the trappings of the consumeristic urban world. I may be accused of a gross generalization when I say this, but nearly every Adivasi I encountered in my journeys through their jungles, was so simple in his/her outlook to life, death, nature, the world, that it made me wonder if the rest of us feel Fear because perhaps we Know more than is necessary? Oonga is fearless precisely because of his innocence — his naivete. This is an ideal I tend to romanticise. Embodying this in an adult would smack of a blinkered over-simplification. A child protagonist allows a storyteller to get away with a lot of things. I can make a nuisance of myself through all the dozens of comments I seek to make, if I make them through the perspective of a child. I learnt this from the Iranian cinema of the 1980s and 1990s. The storytellers were up against so much censorship and Fascist control that they had to rely on Suggestion rather than Statement to make the political commentary their films so successfully did.

Nandini Sen Mehra: As much as Oonga is poetic and lyrical in parts, with the beautifully interspersed elements of magic realism, it contrasts so very starkly with the unflinching brutality, the unfiltered violence that the reader is forced to confront. I would imagine both those sensibilities exist within you as an artist. Do they ever come in conflict in your storytelling and if so, how do you resolve the inherent tension between them?

Devashish Makhija: I try not to.

Many years ago, as a little child, from my first floor balcony, I watched a man being chased. The man’s clothes had been ripped away. He was bleeding. And the two men chasing him had swords in their hands. I was 8. Barely high enough to peek over the verandah wall. The man being chased was stumbling. The men chasing him slashed at him with their swords.

Most of it is sort of blurry to me now except for one thing. Every time his pursuers turned to check if they were being watched, I would duck. I remember not wanting to be seen. I remember being cold and clammy. I remember feeling the urge to piss in my shorts. I remember my throat so dry I couldn’t gasp. I remember my heart thumping. I remember feeling very, very afraid. First for myself, and then for the man being hacked.

I never forgot that… that I felt afraid for myself first.

The man was pleading, screaming, begging, as he ran, tumbled, fell, got slashed, got up again, ran. After that everything is a blur. I cannot remember if his attackers killed him right there. Or if he managed to run down the street and out of sight around the corner where he screamed one last time. I don’t know now if I imagined some of the details. Or if they even managed to kill him. But I do remember my fear. And I carry that guilt.

I did not respond to those pleas for help. I did not raise an alarm. I did not show myself. I remember going down on my knees, shielded by the verandah wall, and crawling back into the house on all fours. I remember crawling all the way into my bed, and trying hard to erase what I had seen and heard. I couldn’t.

I’ve carried this guilt inside of me all my life. If that man died that night, he did not die because of his pursuers. He died because of me. Because of people like me.

We don’t like to confront violence because we don’t like to acknowledge it.

I use the word ‘violence’ because if I said ‘injustice’ I’d run the risk of alienating some of us. What appears unjust to one might seem like ‘justice served’ to the other. But ‘violence’? We can all agree on what it entails. And then I would like us all to acknowledge it, be unsettled by it, so that hopefully we may learn to not allow it to recur.

The unflinching exhibition of violence as it occurs seems to wriggle its way into all my work. I cannot escape it. It must be my guilt from all those years back. I don’t know if I ever seek to resolve the inherent tension between the violence and the poetry. I allow the fractures between them to remain. So that one can be picked neatly apart from the other. So that we are forced to acknowledge the violence we otherwise would like not to.

Oonga, by Devashish Makhija, Tulika Books, pp. 300, Rs 295

Nandini Sen Mehra: The book forces an examination of the relationship between man and nature, the interconnectedness as much as the conflict. It took me to Rousseau’s ‘the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.’ In the writing of this book, did your own thoughts and ideas about this further crystallise?

Devashish Makhija: If I may reproduce the Foreword to the book… it sort of answers this question.

“Imagine a large corporation uses all its might to take away a simple Adivasi’s forestland for almost no compensation.

Imagine the corporation brutalizes this once lush land for mining, leaving it a toxic wasteland.

Imagine they extract a whole lot of bauxite from this land.

Now imagine all the aluminium they extract from this bauxite.

Imagine this aluminium makes its way to factories to be processed into little metal parts for circuit chips…

…which are then exported to a laptop manufacturing company (because a lot of such metal for such electronic parts comes from India).

Now imagine a writer in Mumbai buys one of these laptops.

Imagine this very writer is so moved by the plight of such Adivasis that he writes a story around such a situation in one such Adivasi village…

…on this very laptop.

Symbolically that Adivasi’s misery made way for this writer’s tool of choice.

And unknowingly this writer is paying some unseen karmic debt by writing that Adivasi’s story.”

This story probably did make me meditate more closely on this interconnectedness between nature and man and conflict. But I can’t say for sure. There are too many ironies inherent in even acknowledging it.

Nandini Sen Mehra: Finally, apart from Oonga, who it is impossible to not fall in love with, without giving too much away, the moral courage of Hemla, as the idealistic school teacher, moved me deeply. In her rejection of violence, her faith in a common language as a bridge to understanding between peoples, her inviolable conscience, I found a glimpse perhaps of the philosophical underpinnings of the book. Would you take us through your own thoughts on violence justifiable as a means to an end, when there is a breakdown of the social contract that binds us to one another, and secondly, the role of language as a barrier as well as a pathway to understanding and resolution of conflict?

Devashish Makhija: Hemla, a tribal schoolteacher who finds herself stuck in the crossfire between the CRPF and the Naxalites, was inspired in part by the case of Soni Sori. Studying what she had to endure helped me explore the heart-breaking helplessness of someone who decides to not resort to violence even though the only language being spoken on either side is one of gunfire and animalistic brutality.

To understand the role of Language itself — both as the cause of conflict, as well as the only thing which may allow the dialogue to resolve it — it was important for me to present a more rounded perspective on all sides.

To understand the role of Language itself — both as the cause of conflict, as well as the only thing which may allow the dialogue to resolve it — it was important for me to present a more rounded perspective on all sides.

Pradip and Sushil, the CRPF jawaans — one older and cynical, the other a fresh recruit, and always bewildered — find their origins in a little incident I was party to on that same trip ten years ago through the tribal belt of south Orissa and north Andhra. Most CRPF camps there had been set up in school premises, just like in Oonga. Since we were three city people footing it through the jungles, we were skeptical of the queries we might encounter at such camps, so we steered clear of most of them. Trying to circumnavigate one in Malkangiri, we were spotted, and approached by a CRPF jawaan. Surprisingly, the first thing he said to my journalist friend Javed was that there was no water in his camp, and the jawaans had to go fetch some from the tube-well in the village. He sounded scared. Scared was the last thing we thought someone like him would be. He requested Javed to write about the force’s plight, too. I didn’t know what exactly to make of that, but many years later, while writing Oonga, this episode textured how I perceived the ‘other’ side in this story.

Pradip has seen so many combing operations, brutal interrogations, murders and rapes that he cannot draw the line between the official and the personal anymore. His cynicism is a defense mechanism to be able to make it through this life without self-destructing.

Pradip has seen so many combing operations, brutal interrogations, murders and rapes that he cannot draw the line between the official and the personal anymore. His cynicism is a defense mechanism to be able to make it through this life without self-destructing.

Sushil possesses the same naiveté also seen in Oonga. To some extent, Sushil is hopefully a proxy for the reader. He knows little about how messy the situation is. And he is shocked by every brutal act he witnesses. He, too, is brimming with questions, but like most of us, he, too, is afraid to ask them.

The Adivasi quite evidently are the victims of a national preoccupation with industrial development.

The Naxalites are mostly those Adivasis who have lost and suffered too much (in their opinion) to be open to any sort of dialogue anymore. They have become victims to the deafness that such chaos brings, because of which neither side is willing to hear the other out.

There is a similar angle — mostly unreported — with the CRPF as well. A good number of agricultural (even tribal) youth from other states, who have lost their land to industry / mining, get recruited to the CRPF, and get postings in states where they don’t speak the local language (and therefore won’t easily relate to the locals’ struggles). Making them victims too, of a perverse perpetuation of this cycle of violence.

In the midst of all of them then, Hemla represents the few of us who still struggle to have faith in that cornerstone of democracy — Justice. But in the aforementioned scenario — where no ONE party can be unanimously held accountable for the mess — who is, therefore, punishable? And if no one is, then what is the crime that is being committed? And if there is none, then why is it the Adivasi who pays the heaviest price, losing their home, limb, life, and culture?

Most such conflict emerges from the same seed issue — a lack of communication. For that this story had to be in multiple languages — those of the indigenous people, and those of the outsider agencies being sent in to implement their top-to-down policies. In a first of sorts perhaps, this book uses different fonts to distinguish the different languages being spoken. I struggled with this a lot before Tulika and I arrived at this solution. Here was a story that sought to explore conflict-borne-of-language in a country with more languages than it can make peace with. And here I was writing it in English! How then to raise these questions in the readers’ minds if we can’t make the reader feel this disparity of tongues?

Hemla — who believes in addressing this very conflict, at the grassroots — is someone who speaks both languages then, so she can exemplify some solution to such a deep-set problem. But is her solution tenable? Is non-violence sustainable? Does the Adivasi stand a chance against the juggernaut of development?

I don’t have the answers.

I only know that I grapple with the same things the characters that populate Oonga grapple with. And this story is my way of tossing all these questions out at all of us as reminders of the mistakes we continue to make in never-ending loops through history. I believe reminders reinforce resolve. And cultivating some resolve may bring us to some resolution someday.

I may not live to see that. But hopefully this book will.

Oonga is available here

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated