Argentine writer Gabriela Cabezón Cámara, whose novel, The Adventures Of China Iron, was shortlisted for the 2020 Booker International Prize. Photos: Booker Prize Foundation

Celebrated Argentine writer Gabriela Cabezón Cámara, who was shortlisted for the 2020 Booker International Prize for her novel, The Adventures Of China Iron, talks about how her novel is the celebration of the colour and movement of the living world, the open road, love and sex, and the dream of lasting freedom

Buenos Aires-based writer Gabriela Cabezón Cámara, 51, is one of the most prominent figures in Argentinian and Latin American literature, who has also carved out her identity as an eminent feminist intellectual in the region. Her explosive, exhilarating debut novel, La Virgen Cabeza which was translated into English by Frances Riddle as Slum Virgin in 2017, took us to the slums of Buenos Aires, revealing the dark nexus between the government, the mafia, police, sex workers, thieves and drug dealers. She followed it up with Romance de la negra rubia (Romance of the Black Blonde, 2014) and two collections of short stories. In 2011, she published the novella Le viste la cara a Dios (You’ve Seen God’s Face), which explored human trafficking and was later republished as a graphic novel, Beya (Beautiful), illustrated by Inaki Echeverria.

Her latest hallucinatory novel, The Adventures of China Iron, set in 1872 amid the pampas of Argentina, which was shortlisted for the 2020 Booker International Prize, is a “subversive retelling” of Argentina’s foundational gaucho epic Martin Fierro and “a celebration of the colour and movement of the living world, the open road, love and sex, and the dream of lasting freedom.”

Iona Macintyre, Senior Lecturer in Hispanic Studies at the University of Edinburgh, and Fiona Mackintosh, a Senior Lecturer in Latin American Literature at the University of Edinburgh, have translated the novel into English. Iona’s teaching and research has focused on nineteenth-century Spanish American history and culture. Within this area she works primarily on Argentina, history of the book, translation studies, gender studies and transatlantic relations. She has also published on the contemporary fiction of Jorge Accame.

Mackintosh’s research interests are in gender studies, comparative literature and literary translation. She specialises in Argentinian fiction and poetry and has published extensively on Alejandra Pizarnik and Silvina Ocampo in particular, as well as on contemporary authors. She has translated Luisa Valenzuela’s The Other Book for Bomb magazine and selected poems by Esteban Peicovich for In Other Words. She is currently writing a book on the novels of Claudia Piñeiro.

In this interview, Gabriela Cabezón Cámara talks about how the novel began as a “joyful burst of laughter” in her body, how she conceived the novel as “a loving dialogue with José Hernández’s work and why it’s important for us to be able to imagine other possible worlds. Excerpts from the interview:

Nawaid Anjum: The Adventures of China Iron, set in nineteenth-century Argentina, is a hilarious and thrilling story with sexual discovery and personal freedom as its underlying themes. Is this how the novel began in your mind?

Gabriela Cabezón Cámara: When I had the idea of writing the life story of China — it wasn’t simply an idea, it felt like a joyful burst of laughter in my body — I knew straight away that I wanted China to have a luminous life, worlds away from the kidnapping, humiliation and never-ending oppression that blights the life of her poor ex-husband, Martín Fierro. I thought, and felt, that her destiny just had to be full of light, like the grasslands of the pampa, like that of people who are lucky enough to reach great heights after having hit rock bottom. Sexual discovery and personal liberation are, undoubtedly, a very important part of any life worth living.

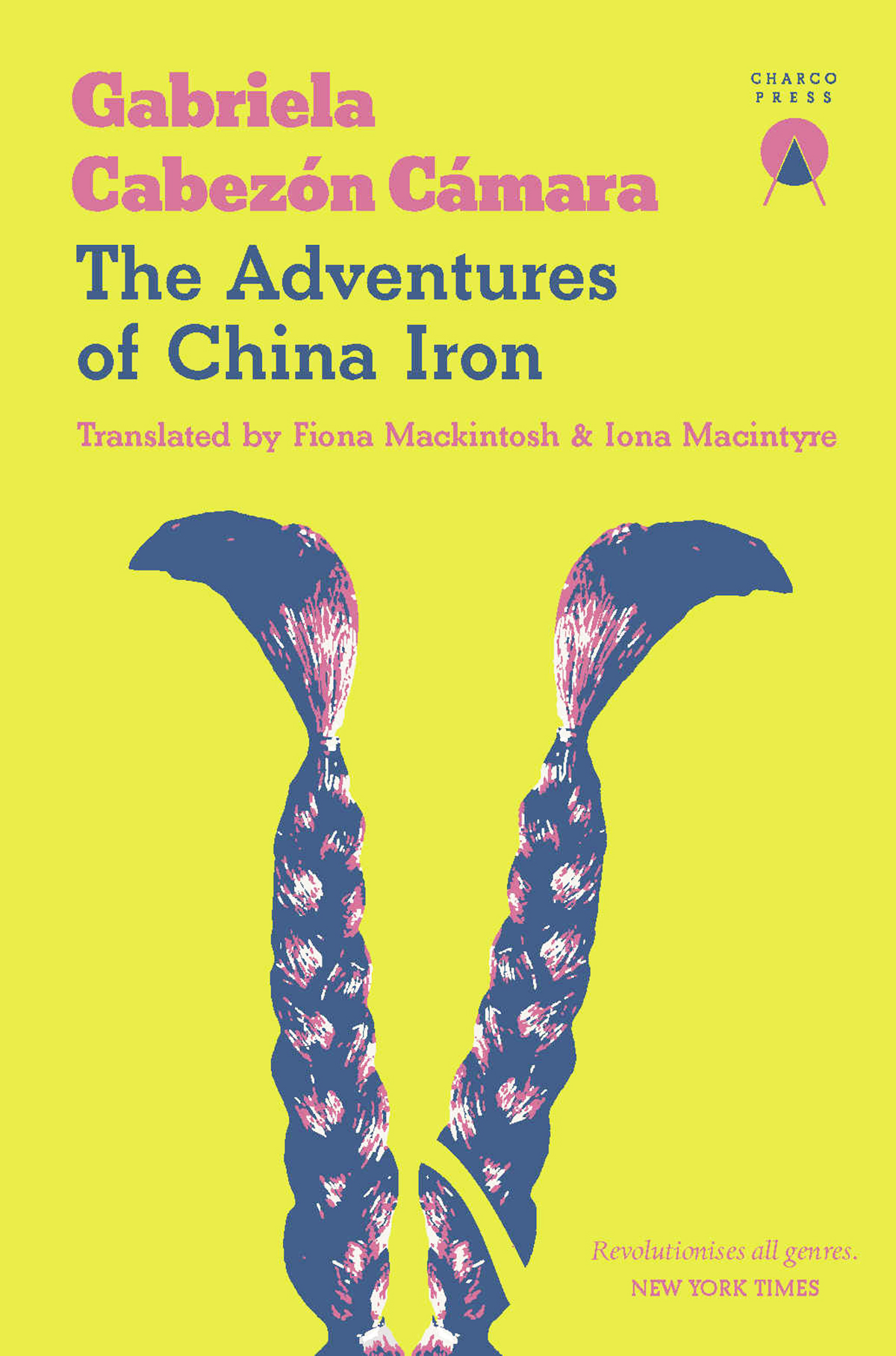

The Adventures Of China Iron, By Gabriela Cabezón Cámara, Translated by Iona Macintyre and Fiona Mackintosh, Charco Press, pp. 200, Rs 799

Nawaid Anjum: José Hernández’s poem The Gaucho Martín Fierro — about a gaucho who deserts the army, forms a brotherly partnership with another man, and eventually settles amongst the indigenous peoples of Argentina – is entwined with your novel and Hernández also appears as a character. Did you want your novel to be a counterpoint to his rigid and hyper-masculine rhetoric or a kind of retelling of his poem?

Gabriela Cabezón Cámara: I conceived of the novel as a loving dialogue with Hernández’s work. Ironic, yes, but also loving: Hernández’s poem is really beautiful, especially the first part,‘La ida’, (‘The Departure’). I would say that the two poems are quite separate because ‘La vuelta’ (‘The Return’), the second part, is inscribed in the ideology of the ruling classes. Hernández had gone from being a persecuted politician to a government official and a famous, influential writer: he knew he had power, he knew how many people were reading his work. That strips away his literary weight in the second part of Martín Fierro. He writes a manual for resignation for the burgeoning citizens of Argentina. ‘La ida’ is escape, it’s the search for a good life far away from your oppressor, the discovery of love — in the poem they call it friendship but let’s remember it was written in 1872 — and a journey to the Other in Argentina: the Indian. If I was thinking about taking a counter-position it was with this undeniably ultra-masculine logic, which is also particularly oligarchical; it’s the logic of landowners, the logic that was imposed during the struggles over how to construct the Argentinian state. At the end of the day, it’s a logic of submission to empire. I firmly believe that Hernández’s poem/novel narrates the end of the constitution of the Argentinian state and shows exactly how it was from then on: the imposition of the economic unit of the landowner over small parcels of land and small producers. Tellingly, Fierro declares that he has “children, an hacienda and a wife”, in that order.

Leaving the implications of the wife’s position aside, let’s talk about haciendas. Fierro was a small producer. The sector of the country that prevailed and imposed its conditions did not want small producers, it wanted everything for itself. This led to what became known as ‘The Conquest of the Desert’ in Argentina, which although it wasn’t a desert, was certainly a conquest: it was the extermination of all native peoples so as to be able to use the whole land with impunity. This is the reason why Fierro is conscripted and taken away from everything he had in life. That’s the story of the poem/novel. Taking Martín Fierro as a starting point, I tried to express another possible idea of nationhood. One that does not commit genocide or ecocide nor deprive people of their basic rights.

Nawaid Anjum: The novel is divided into three parts: The Pampa, The Fort, and Indian Territory, with each part made up of short chapters. The first part, which is also the longest, establishes China's journey of self-discovery as she is picked up by Liz, a Scottish woman, and they subsequently set out and are lost in a red-hot passion for one another. How did these characters and their journeys — both through the outside world and into each other — come to you?

Gabriela Cabezón Cámara: I love what you say there: “come to you”. That speaks to the creative process, something that isn’t talked about that much. The things that come to you when you concentrate enough, when you give time and space to an image and it grows, you just let it grow, and then something magical happens: characters come to you with their journeys and their stories, they don’t come out of you, they come from somewhere else. Maybe from language, the social imaginary, other books, conversations with friends, what you see on TV, having a chat with the grocer, walks with your dogs? Or from all those things. They come from somewhere else and strike you, and you give them a body and hands and something of your own distinctiveness. That’s how they came to me, from desire, from the pleasure I get and have always got from reading adventure stories, from my urge to narrate beautiful lives, from my desire to have a beautiful life, a vital life. A vital life: it sounds like tautology, but it isn’t.

China came to me through the poem: she is named China and nothing else is known about her. That was the first thing that appeared to me when I thought about writing this novel: a really, really young girl who frees herself. As for Liz, in Martín Fierro, there is mention of an Englishman who is taken by the military by mistake: I imagined a woman looking for him so then there were two women who’d head into Indian Territory. One to escape from her husband and the other to find her husband. One that doesn’t know anything about the world outside of her tiny village. And another who comes from a far-away country which has become the centre of the universe. From their meeting, and the Anglophilia they share but eventually abandon in the hope of creating a better world, the novel was born.

Nawaid Anjum: The tone shifts in the second part which seems to be a kind of meta-narrative. It is here that we are introduced to José Hernández, author of Martín Fierro. What was the idea behind bringing in Hernández as a character? Though he fades away in the narrative, overridden by an ecstatic sex scene, his character is certainly a bold statement in the novel, akin to looking rigidity and conservativism straight in the eye.

Gabriela Cabezón Cámara: José Hernández was a poet, politician, and a cattle rancher. He actually wrote a treatise on ranching, a manual for turning an estancia into a modern factory. In the novel, Hernández represents that whole sector of the nation that had been successful at imposing its interests. To bring their plans to fruition they had to subjugate, oppress and massacre other sectors of society. And they did, the consolidation of the Argentinian state was very cruel, as well as racist, classist and machista. It’s absolutely true that that part of the novel is a fierce critique of the rigid, cruel and conservative centre of power, though I think and hope that it’s also got its funny side, and is not totally devoid of compassion.

Iona Macintyre (top), Senior Lecturer in Hispanic Studies at the University of Edinburgh, and Fiona Mackintosh, a Senior Lecturer in Latin American Literature at the University of Edinburgh, have translated the novel into English

Nawaid Anjum: In the final part, the reader is reminded of the conservative figure who has vanished into the vortex of the narrative, there is also a subtle hint about the need to know that it’s a figure that is always looming. In some sense, the novel seems to juxtapose the world these two women inhabit with the one Hernández does and apprises the two of this world’s inherent dangers. Did you want the conflict between their two worlds to be the heart of a novel — the masculine narrative versus the feminine one?

Gabriela Cabezón Cámara: I’m not completely sure in my own mind but yes, there is something of that. I mean, the masculine storyline isn’t just masculine in the novel: it’s the storyline of the might of the powerful. There are other male characters, Rosa the gaucho, and in the third part, Martín Fierro himself, both inscribed with light and happiness. And there are other female characters like the monstrous Miss Daisy. But perhaps we could speak of a masculine storyline as the storyline of the bourgeois, patriarchal, white power and a feminine storyline as that of the anti-bourgeois, anti-patriarchal, non-white rebellion — white people are there but the culture of the community that they form owes much more to native cultures — and so yes, it’s like you say. The revolution of today is a feminist movement full of people from all classes, all genders, all cultures — but I believe it has its foundations in indigenous cultures from the south because we urgently need another way of life, one that is anti-speciest and able to imagine and develop its existence in harmony with nature.

Nawaid Anjum: In a changed world, what role do you see fiction writers around the world playing?

Gabriela Cabezón Cámara: I think that one thing that we writers can do is work on narratives which are not narratives of the end or obedient narratives, narratives which are resigned to the world coming to an end before capitalism does. It’s important for us to be able to imagine other possible worlds. It’s vital, it’s urgent: we cannot docilely give in to the end of the world, to cruelty, to pollution, to the death of almost all the forms of life with which we currently coexist. Without the survival of forests, of animals, of insects, of rivers, there is no life worth living and probably no life, full stop. I wouldn’t say that this is the role, I would say that it is a possible and desirable role. It’s a role that I’m certainly interested in.

Nawaid Anjum: Could you name some contemporary writers writing in Spanish who need to be read by the world?

Gabriela Cabezón Cámara: Selva Almada, Carlos Ríos, Roque Larraquy, Vera Giaconi, Carla Maliandi, Alejandra Zina, Julián López, Alejandra Costamagna, Sebastián Martínez Daniell, Liliana Colanzi, Camila Sosa Villada and many others. I could write fifty pages of names.

Nawaid Anjum: What are you currently working on?

Gabriela Cabezón Cámara: On a novel that takes place during the classic era of the conquest and is set in the Basque Country and in Tucumán. I use the term “the classic era” to talk about the conquest because sadly it never ended in Latin America. It’s still happening here. On every hectare of land that is stripped, in every forest that is burnt, what remains of our indigenous peoples is being killed. And even that only remains because of their massive, heroic and unsung resistance.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated