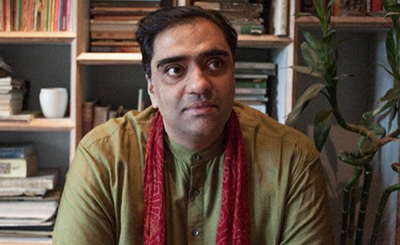

Anjum Hasan. Photo: Zac O'Yeah

The first piece of writing that I read by Anjum Hasan was her essay, “Shillong, Bob Dylan and Cowboy Boots” — it won her a prize at the Outlook Picador Non-fiction Contest. It was 2002, and the essay about the rich cosmopolitanism that characterises the music scene in her hometown, Shillong, gripped me immediately. It was impossible to not notice the striking confidence of the voice in the essay. A few years passed, the Internet gave an interesting new life to Indian English poetry, and I began to come across poems by Hasan — the subjects of the poems came invariably from her lived life, places visited, remembered histories, an architecture, both of man-made constructions and the mind. By the time one came towards the end of the poems, something magical would happen and the places and the people and the possibilities that made them relatives would transform into something or someone familiar, recognisable but kept hidden inside us for fear of the stab of truth. Soon, in 2006, Sahitya Akademi published her first collection of poems, Street on the Hill. Since then, over the last decade, Anjum Hasan has published three novels and a collection of short stories — Lunatic in My Head (Penguin-Zubaan 2007), her first, is an extraordinary debut novel about the lives of people in Shillong, a young professor who is frustrated about teaching Shakespeare and Ernest Hemingway in college, a little girl who makes a home inside books to escape from the drudgery of her parents' lives, young men whose lives are fuelled by romance and relationships and music, all these people living most of their lives inside their heads, which also explains the title. There are few studies of Indian provincial life as rich as this novel. Two years later, Neti, Neti, its sequel arrived — the little girl, Sophie, had now travelled to Bangalore. Hasan's novel painted a semi-lost generation for us, a middle-class youth spurred by ambition, unsure about the pipelines that separated work and fun, the day and night life, love and romance.

Difficult Pleasures, a collection of stories, was published in 2012. It proved to her readers again, that Hasan's expertise lay in entering and analysing people's minds for these were stories about people who led near solitary lives, mostly in cities, and were afflicted by a weariness that characterises modern life: relationships, not just with lovers, but with parents and employers; the ailments of the city, water shortage and traffic jams; of silent, even depressed, lives; and of that thing that is precious to the Anjum Hasan world — literature, both as idea and as practice, home and escape.

Her most recent novel is The Cosmopolitans, an adventurous novel of ideas that traces the life of Qayenaat, an art critic, her relationships with lovers, old and new, and what art means in India today — new age art and art that is a sediment of heritage. It confirms, not for the first time of course, Anjum Hasan's fierce intelligence, both as writer and thinker, and it gives voice to an artistic consciousness that has rarely found space in the pages of the Indian English novel.

Excerpts from an interview:

SUMANA ROY: To begin from the beginning. Will you take us through your childhood? The people, places and things whose influence you can spot only now.

ANJUM HASAN: I grew up in Shillong and it was in many ways an ordinary Indian middle-class childhood of the late 1970s and ’80s — insulated, comfortable but not over-privileged, education at the centre but achievement not fetishized. My siblings and I would spend a lot of time outdoors, I was regularly scraping my knees and twisting wrist or ankle. But I also read a lot and in that entranced way that made the real world recede. I think I was always bored with too much reality. Much later I read in Jean-Paul Sartre’s autobiography, Words, that he lived in an upside down world as a child, imagining that what was in books was real life and real life a paltry fiction. As for influence, I think everything influenced me. But influence can also be retrospective. Which is perhaps another way of saying that the significance of memories changes with time.

SUMANA ROY: Can you recollect any episode or event from that period that made you want to — decide on — become a writer?

ANJUM HASAN: I’m often asked that question and my answer is always the same — I don’t think so. I always had a romantic attachment to the idea of writing — and all the attendant paraphernalia: libraries, notebooks, wooden desks, sharpened pencils. It was an a priori attachment and perhaps an empty one. I didn’t know what I wanted to write about but I knew I wanted to write. Giving meaning to that desire has been the story of my life — or one story of my life.

SUMANA ROY: You know, when I first read Lunatic in My Head — and it’s a novel I continue to be partial to — I did not know about you, except from the bio notes. The magic of the world in that novel, deriving its fuel from the literary imagination, made me imagine your childhood, with your siblings, in a cold rainy hill town as similar, in however tangential a way, to the world of the Brontës. Would you like to respond to that?

ANJUM HASAN: As child I used to have an abridged Jane Eyre, an Indian edition printed on cheap paper that I remember being very attached to. And I didn’t study English literature but my elder brother was doing it in college so I read his copy of Wuthering Heights and was very taken by its atmosphere. The Victorian world of the Brontës couldn’t have been the same as ours, but I do remember our joint creativity when we were younger — writing and putting on plays, giving poems to each as birthday gifts and so on — which, thinking about it now, is perhaps similar to the closeness between the Brontë sisters. And then my sister Daisy wrote a novel as well and my brother, Adil, wrote and published poems and stories when he was younger. But by the time I myself embarked on Lunatic, I wasn’t really thinking of the Brontës. I had moved to Bangalore by then and Shillong itself seemed like a mythical place to me, it didn’t need another literary source to illumine it. And it’s usual for the comparison to run in one direction — Shillong is like the Yorkshire Moors or Scotland or whatever. But the Yorkshire Moors could also be like Shillong.

SUMANA ROY: In this connection, I’d also like to ask you — again, just out of curiosity — whether you and your siblings had a paracosm of your own?

ANJUM HASAN: Perhaps we did live in a slightly make-believe world. It could just have been the spirit of the times. There was no television for us, except occasionally at the neighbours, till the mid-80s and one drew much more on one’s own resources for amusement. Being in Shillong also contributed, the feeling that one was in a small place, distant from the centre, wherever that was.

SUMANA ROY: You spent nearly half your life in the mountains, the other in the plains, before choosing to live in the mountains again. This geography, not just the mountains and the plains, but also the North-South polarity, has that affected your work?

ANJUM HASAN: Right now I live half in the hills and half in the plains — or on an overcrowded plateau, which is what Bangalore was. Maybe this is the only way for me to exist: in undecidedness. I think the north-south, hill-plain divide has given me a sense of scope, experiencing these constant shifts of landscape and language and people as new realities each time. And so I am a different consciousness in each place, tuned to different things, which is disorienting but also productive. The quality of each place — Bangalore’s entrepreneurship-driven energy, Coorg’s relative gentleness, Shillong’s degeneration — enlarges the possibilities of what I can write about.

At Jaipur Literature Festival. Photo: Nafis Hasan

SUMANA ROY: How has your training in philosophy affected your writing?

ANJUM HASAN: I haven’t felt inclined to write philosophical novels, the kind Iris Murdoch did, for instance, in which the characters debate philosophical concepts. I’ve always been attracted to seriousness, though, and to characters in fiction who are shaped by intellectual ideas. Perhaps that drew me to philosophy as well; at a certain stage in my life it seemed the most serious thing one could do. I’m not very well-versed in Murdoch but am thinking of some of the American Jewish writers — Chaim Potok, Bernard Malamud, Saul Bellow — as well as a wonderful Israeli writer called Amos Oz, all of whom I was reading a lot as a teenager and in my early 20s. Their characters can be highly grave and studious, though Bellow’s are also comical and shambolic.

Chaim Potok has a novel called The Chosen about an intense young Jewish man reading philosophy and psychology in New York and I was absolutely in love with that as well as with the ideas of a life devoted to study in Amos Oz’s My Michael. I think all this broadly fed into my understanding of an intellectual life but by the time I started writing fiction I was more taken with contemporary Indian life, its contradictions and hollow spaces, and the need to find a language to talk about that.

SUMANA ROY: After the three novels and a collection of stories, can you now see that you had been gravitating towards the novel of ideas right from your first novel? Literature, and a life invested in it, to art, and the habitation of that space by both its producers and consumers?

ANJUM HASAN: True, but in the process of writing that novel of ideas something intervenes — what one might call daily life or mundane reality. It’s from that end that I approach art and literature rather than as an idealisation. So whether it’s young men listening to Pink Floyd in Shillong or Qayenaat in her Bombay flat dreaming of being an artist, there’s always something else going on alongside. I don’t know if I can afford to write about the art only. It seems indulgent as well as untrue.

SUMANA ROY: Again, in this connection, I’d like to ask you a personal question about how you see — live, study, analyse, write about — the life of the mind? Has this reflected in the life choices you have made — your relationships, the places you have made home, and so on?

ANJUM HASAN: Well, I’m married to a writer. But I’m also increasingly feeling that one can’t afford, as a writer, to live only a literary and inward-looking “life of the mind”. There is a great pull towards that, of course, as I’ve said. To retreat with one’s books and ideas into oneself and be literary in that way. But time and again one is brought back to the class one belongs to, the society one lives in, and the need to reflect on that. That’s my struggle as a fiction writer, as it probably is for so many others. How to make that awareness and those questions enter the fiction and make it speak to its time while retaining its integrity as fiction?

SUMANA ROY: Two things: your time at India Foundation for the Arts (IFA), and now as Books Editor at the Caravan. How has that affected your writing? Have they given your writing a new trajectory, an unfamiliar ambition?

ANJUM HASAN: I worked for a decade at the foundation and, even as it sharpened my desire to go off and write, break away from the tedium of an office job, it also exposed me to art — and the way we talk about it. The best education was travelling across the country to meet people involved in all kinds of projects. That was great exposure to the rhetoric around Indian art and also the passions involved. The Cosmopolitans draws on some of things I was mulling over in those years. Working at IFA also gave me the chance, for the first time, to ask myself how I relate to Indian culture. It’s a question every westernised Indian probably faces at some point, and in my case working at IFA was the trigger. Caravan has been an incredible opportunity, especially the chance to learn from colleagues how to push the envelope in journalistic writing, and the cultivation of well-argued, well-substantiated writing as an ethic. Caravan has raised the bar in so many ways but the biggest contribution, I think, is how it questions the ingrained culture of patronage in public life. I don’t know if working there has directly influenced my writing but being Books Editor has given me a chance to read much more Indian writing than I had and that has certainly been eye-opening.

SUMANA ROY: Very few contemporary writers have written about the Woman in the City with your depth of understanding and compassion, and your sharp critique and analysis. Has this been a part of your ambition as a fiction writer? Is this allied to your own experience as a woman in the city?

ANJUM HASAN: I do write about female characters but never without a certain wariness because I may disappoint the reader looking for a feminist angle. Perhaps it is connected to my own experience. If I had known more trouble as a woman, for instance, I might have gone into the subject of subjugation or discrimination. But I’m also aware that we’re living through a revolution where women are concerned — at no time before this have so many women been out of the home, working, visible, audible, self-contained. So there’s a sense of this as ordinary, taken for granted operating in my fiction — that the traditional challenges before the middle class woman have been sorted. Yet the fact that one can write about a woman being liberated in this way is possibly revolutionary in the Indian context.

Anjum Hasan with her sister Daisy Hasan, author of The To-Let House. Photo: Zac O’ Yeah

SUMANA ROY: Can we spend a little more time talking about the most interesting girls and women in your fiction? Sophie, Firdaus Ansari, Qayenaat, and the other interesting women in Difficult Pleasures. There is a common thread running through these characters, isn’t it?

ANJUM HASAN: Is there? I’m not consciously working out any theory as I write about them but as I’ve said I’m aware of how these characters enjoy certain new freedoms, which their predecessors, in life and fiction, didn’t. What interests me is taking off from there. Seeing that they are free as women, then going on to ask how they might become free as individuals.

SUMANA ROY: What I am trying to ask you is this — have you chosen this urban aloneness as one of the themes you want to explore through your fiction? Sophie, Firdaus, Qayenaat — they are terribly attractive to me for being so self-contained, and yet there is this constant tussle between loneliness and aloneness.

ANJUM HASAN: The themes seem to choose you rather than the other way around. And, yes, I’m taken with characters who want to be alone but are also lonely. Putting them in that position helps me break away from stereotypes — they don’t necessarily represent this or that, they are themselves. Their main project is themselves.

SUMANA ROY: Was it a conscious choice to write about a 53-year-old woman?

ANJUM HASAN: Certainly. It’s intrinsic to her story, being of that age, having lived through certain eras, feeling the weight of time gone by. I’m amazed by how much attention has been focussed on that. I was aware, writing about her, that one doesn’t read too many novels about older women but I didn’t quite realise that it would be met with so much shock, though so far it seems to be mostly delighted shock.

SUMANA ROY: Literature. Music. Art. The subjects of your three novels in a way. Who are the writers you like reading, the artists that move you, the musicians that live in your iPod?

ANJUM HASAN: All of it changes as one changes but if I had to look for some consistency or pattern in what is attractive to me in literature, art and music then it would have to be that which speaks in a lyrical way of the ordinary. So the poetry of Arun Kolatkar, Philip Larkin or Cesare Pavese, for instance.The whole singer-songwriter tradition in Western pop music, from Bob Dylan to Kimya Dawson. And in art, the urge in the Impressionists, say, to capture life in quick brush-strokes as it was passing, or the later Ashcan School whose paintings drew from New York life, or Indian artists as different as Ram Kinkar Baij and Subodh Gupta.

SUMANA ROY: Let’s talk a bit about “Small Town India”. We’ve seen writing about that space fill out in a variety of ways, but there’s been nothing like the small town that Qayenaat encounters in The Cosmopolitans. Was that a conscious decision, too, to tear the skin of cream that was forming on the surface of this new body of writing?

ANJUM HASAN: I think Madna, the town in Upamanyu Chatterjee’s English, August, is quite dire and very real, as seen from Agastya’s eyes. And then, of course, there’s Malgudi, which has set the standard for how to write about the provincial modern. I wanted to see if Simhal, in my novel, could be provincial in that sense — minor and off the map — but also hiding some larger ambitions, a deep sense of grandness, however misplaced.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated